|

Last year my brother Daniel released an EP with five songs on it. It was called At Last - Far Off, and it has some of the most beautiful worship arrangements on it. One of my favorites is Psalm 77--it is such a simple refrain, but one that is refreshing and humbling.

Worth listening to, especially during this time of advent. Or check out his new single just released for Christmas, Puer Natus Est. Basically, just listen to his stuff. It's all good.

0 Comments

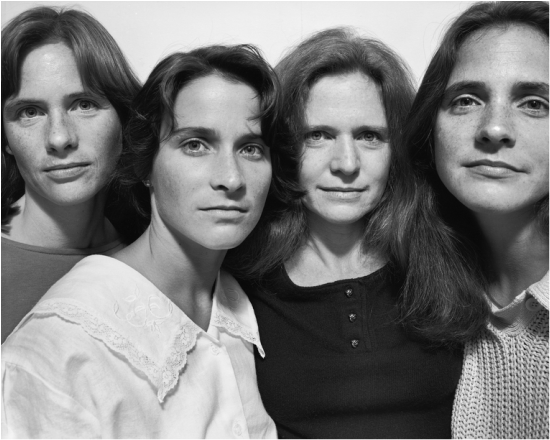

Nicholas Nixon began taking photos of his wife and her three sisters in 1975, and has taken a photo every year since. The result is incredible.

"Throughout this series, we watch these women age, undergoing life’s most humbling experience. While many of us can, when pressed, name things we are grateful to Time for bestowing upon us, the lines bracketing our mouths and the loosening of our skin are not among them. So while a part of the spirit sinks at the slow appearance of these women’s jowls, another part is lifted: They are not undone by it." -Susan Minot, writing for the New York Times This photography project is one of the simplest and most beautiful I have seen in a long time. As we click through these photos, we see, gently and gradually, what it means to be a woman, a sister, a human. As the lines on these women's faces slowly deepen, it's tempting to read into them--to wonder what experiences have shaped them, how each sister differs from the others, and the story of each photograph. But while the four women have allowed us a glimpse of their faces each year, that is all they have allowed us. Their openness--close bed-fellows with their privacy--makes this project remarkable, poignant, and beautiful. Check out the photos and New York Times article here. ~Ruthie I don’t know if it’s the fact that I’m getting older, or if there’s something specific to the way NYC has been shaping me, but I’ve recently been thinking a lot about being able to just be who I am. At this point, while I will always continue to change and grow, I am settling into the woman I am and the way I’ve been shaped. The process of questioning myself doesn’t end, but there are some things I know, and I want to have the ability to just be.

Specifically, I’ve been thinking about this in relation to art, and to being a Christian. I am much less worried about being a Christian than I have ever been before in my life, and that strikes me as encouraging and also kind of embarrassing. This is who I am, and yet for most of my life (and there are still many moments) I’ve been worried about how people will treat me, or what they’ll think, or how they might misperceive my beliefs. But I’m starting to believe deep in my core that it’s okay to just be. I am a Christian. It’s who I am. It’s okay. And I am an artist. This post is about why I am starting to question the label “Christian artist.” This is not the first time I’ve questioned it, but it’s the first time I’m putting it into words. Questions about it have crossed my mind several times recently, most recently when I came across this article about Switchfoot and their contention of the label “Christian band.” (I know this is an old article. But hey, I’ve been busy.) When asked if they are a Christian band, their lead singer, Jon Foreman, says: "To be honest, this question grieves me because I feel that it represents a much bigger issue than simply a couple SF tunes. In true Socratic form, let me ask you a few questions: Does Lewis or Tolkien mention Christ in any of their fictional series? Are Bach’s sonata’s Christian? What is more Christ-like, feeding the poor, making furniture, cleaning bathrooms, or painting a sunset? There is a schism between the sacred and the secular in all of our modern minds. The view that a pastor is more ‘Christian’ than a girls volleyball coach is flawed and heretical. The stance that a worship leader is more spiritual than a janitor is condescending and flawed." I don’t think there’s anything wrong with calling oneself a Christian artist. But I agree with Foreman that there are certain unfair expectations that arise with the label. Like erroneously expecting a pastor to be more pure than his congregation, expecting an artist who is a Christian to only ever create art specifically referencing Christ is severely limiting. Would you expect a bank teller to make a Jesus reference to every customer who comes up to his booth? Or a journalist to work a Biblical narrative into each byline? And yet Christians who are artists are often unfairly expected to reference Christ in every piece of work they create. The genesis of this, I believe, is complicated. I would argue that it is partly cultural, and partly theological. Culturally speaking, it’s closely tied to the fact that in many parts of the West, and certainly in the United States, the cultural consciousness surrounding art is unhealthy. I’ve written about this before, but because art is considered a luxury, only as good as its entertainment value, and primarily an industry--not as a way to share stories and therefore an integral part of life--artists tend to feel the need to heavily justify their decisions to be artists, whether in a monetary sense or otherwise. Theologically, the matter is complicated by the fact that most art in the West during the Middle Ages revolved around the church. In addition, during the Reformation Christians developed the idea that any kind of art during worship needed to be heavily justified, and as art became more important outside of the church, this trickled down into art outside of worship as well. Today, these cultural and theological pressures often take the shape of artists telling their Christian friends that they are pursuing art so that they can either “bear witness in a secular industry,” or use their art as a platform for proclaiming the name of Jesus. Neither of which is a bad thing. But, I would argue, neither of which should be the primary goal in being an artist. As Christians, we are called to bear witness first and foremost in every aspect of our lives. That is certain. But that is true for every Christian, no matter what profession, and it does not always take the form of explicitly naming the name. In some fields, like my father’s field as a physicist, it never does. The great thing about art is that it can take that form. But it doesn’t have to. There is no need to justify a career in the arts any more than to justify a career in plumbing. Art is inherent to humans, and storytelling begins as soon as speech does. As Christians, sometimes we speak in our daily life about how much we love Jesus, and sometimes we speak about how much we love coffee. Artists should be free to speak about either as well. And really, there is a lot of laziness that has come about because of the concept of “Christian artists.” There are many beautiful pieces of sacred art, or stories about Christian experiences that are heartfelt and important. The Biblical narrative is woven through all of us, as Christians, and it should come out of our pores. But there are also plenty of pieces of horribly lazy art and stories with the name of Jesus plastered on simply because there is a market for it. Artists who are Christians cannot be lazy. They cannot rely on a market, as many have. It’s much more difficult to tell a diversity of stories, some of which specifically name Jesus, and some of which don’t, and it’s difficult to interact at all times with a world that holds different beliefs and values and find ways to create and converse with artists outside the Christian faith. But it’s important. It’s a command, to all believers. In the same way, Christians who are not artists must refuse to be lazy as well. It’s much easier to rely on a Christian label or art industry to provide entertainment and enjoyment, for us and for our kids. But we are called to engage in the world, and to feel the pulse of its heart. Doing the work of evaluating art--by artists who are both Christian and not--is important. Some of it you’ll have to throw away. Some of it will touch you deeply. And that’s good. The bottom line is that we are Christians first, and that changes the way we think, speak and breathe. But once it gets into our blood and marrow, we as artists don’t need to be constantly questioning our profession. We fix our eyes on Jesus, and trust in the process of sanctification. Sometimes that means we’ll create art that speaks intimately of Christ’s sacrifice for us, and sometimes it means we’ll write a comedy sketch about the bus stop. Whatever project we’re working on, let’s not be afraid to just be. ~Ruthie *My brother Daniel recommended a book called Art and the Bible by Francis Shaeffer to me recently, which apparently speaks directly to this. Worth checking out!  Women Arriving at the Tomb - by He Qi Women Arriving at the Tomb - by He Qi Friday is moaning and Sunday is laughing, but Saturday is silence. I breathe the deep stillness of both the cross and the empty tomb, but the disciples and the women knew only the pit of having had Him and being left with nothing, and silence weightier than existence, that broke the earth and rewrote it backwards and forwards. Silence that fills lower and higher-- pouring out of a sepulcher that calls forth my adoring wonder. (Last two lines inspired by The Valley of Vision) a two and a half hour sobbing

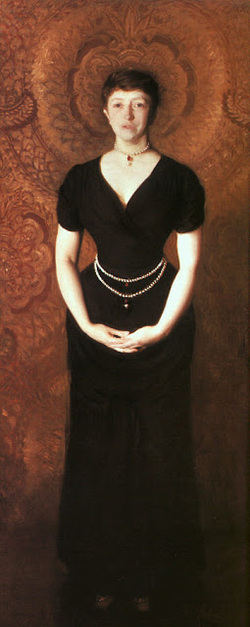

scream for mercy that doesn’t come even with a happy ending, it doesn’t. trapped in history, squeaking folding seats uncomfortable people. pain, over and over flirting with the line--artistic flaw punishing us for things we didn’t do but continue to live with. I’m not the one still suffering. but I am the one asking myself what I would have done: I know the answer. I would have batted my fan and gone back into the house. in my head I speak truth and live with open hands in my heart I just want to be okay and that’s why I squirmed that’s why we all squirmed watching a history that was, and could be again if we forget stripe-crossed backs-- stripes answered only by stripes stripes thank God. no. thank God. ~Ruthie  Hannah and I have decided that every so often, we will write a post profiling a famous, but not widely know, woman from the past. The woman we’ve chosen to be our first is probably more infamous than famous. At least in the Boston area. On a recent visit to Boston, Hannah and I visited the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, which is located in the Fenway area of Boston. On a gorgeous, sunny day, it was a bit surreal to go into the first part of the museum—constructed only in the last couple of years—to buy our tickets. Surreal because of the rest of the museum. The first part is all clean lines and perfect temperature and bright, pleasing colors: a 2012 version of symmetric, breathable classiness. But once you have your tickets, you walk through a glass portal into the museum, and the real fun begins. This is a post about Isabella Stewart Gardner, not her museum. But as I walked through the rooms, I began to sense that the museum and the woman who created it speak volumes about each other. It’s a crazy place, that museum. In stark contrast to the balance and dignity of the newly constructed entryway, the museum (nestled into a huge house that was constructed to look like a 16th century Venetian residence) is a study in disorder. To Isabella, everything had a reason and a place. But to a visitor, it is chaos. I wanted to know more as soon as I began wandering through the rooms. It was clear that whoever had designed the place had very strong ideas about what was important, and it was also clear that she was an amateur. Why else would she have placed Vermeers next to unknown 19th century prints? Why would she have hung a length of green silk cut from one of her own dresses under a Degas, and then placed a 16th century lectern, sporting a massive old manuscript underneath it? The rooms were overwhelming in their eclectic style, and in the abundance of art. Several rooms were hung wall to wall with paintings, drawings and prints. Stepping into them and trying to look at each picture was impossible. And the experience of disorientation was only heightened by the security guards in each room. As I stared up at a painting of a woman with curly red hair, trying to find a mooring for my wandering eyes, I heard a voice close to my ear: “Does this painting…interest you?” I turned to see an elderly security guard standing beside me. I said yes, too surprised and intrigued to say anything else, and he began to tell me in his thick accent about the woman in the painting, and how her granddaughter had stood on the spot where I now stood and told him that her grandmother had had 10 children, and was pregnant in the painting. “And from that moment, I knew, in my heart, this painting, it is the one,” he finished. It was probably the best museum interaction I’ve ever had. As I continued walking around, I knew little more about Isabella Gardner than that she had very odd taste and had written into her will that nothing in the museum could be removed or added. But as I’ve read more about her, I realized that my interaction with the security guard is exactly what she envisioned for her museum. You can feel the eccentricities of her personality even now, almost 90 years after her death. But her museum is still doing what she intended it to do—bring art to Americans, and allow them the space to observe it in a disarming state of chaos. Isabella Gardner was a crazy woman. What else can you call someone who, in 1912, attended the posh Boston Symphony Orchestra wearing a white headband emblazoned with “Oh, you Red Sox,” on it? Or, while building her museum, asked to borrow the beautiful and famous Sargent painting “El Jaleo” from her cousin, and once it was in her house began reconstructing a room to house it? That would make for an awkward conversation—which ultimately ended in the cousin gifting the painting to Isabella. There are many details about Isabella’s life that fascinate me. There is her marriage to John Lowell Gardner (Jack), which was apparently a happy one, despite the loss of their 2-year old son in 1865. After their son died, they began collecting art, and Isabella conceived her dream of creating a museum—which Jack shot down, when he found out she wanted to transform their house. There is the fact that she contacted an architect in secret two years before her husband’s death, and that she brought the same architect (Willard T. Sears) up only ten days after Jack’s funeral to begin designing the museum. Apparently, art was a way of healing for Isabella. But as I read more about her, I became fascinated with the fact that she used her eccentricity, not only to get what she wanted, but to get what she wanted for others, and perhaps even to shield herself from the society of the day. Several accounts talk about how the wealthy Bostonians snubbed her when Jack first brought her to the posh Back Bay neighborhood, and for years to come. It was only towards the turn of the century, when Isabella was in full swing constructing her museum, that the younger generation fell in love with her because of her quick wit and freedom to do whatever she wanted (see above: white head band at BSO concert. Seriously.) And she used her influence—or infamousness—to jump start John Singer Sargent’s career, after he painted that startling portrait of her in black and pearls. (Which she loved, and her husband hated, as evidenced by his words in a letter: “It looks like hell, but looks like you.”) After her death, she left bequests to the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, Industrial School for Crippled and Deformed Children, Animal Rescue League, and Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. As well as endowing her museum and making it impossible to alter a single thing about the layout or pieces on display. (And also neglecting to insure the art. Which was painfully apparent when one of the largest art heists of all time took five Degas, a Vermeer, a Rembrandt, and a Manet—all uninsured.) So I guess the conclusion is, if you’re rich, you can do what you want. You can nail a Sargent to the back of a writing desk and place a 17th century chair in front of it. But Isabella Gardner was a rebel, in her own way, and I tend to think that if you’re going to be an eccentric well-off person, opening a museum and using your craziness to help others—and allowing yourself the freedom to get over the snobby Boston societal shun—is probably the way to do it. ~Ruthie |

Currently Reading

Open and Unafraid David O. Taylor O Pioneers! Willa Cather Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|