Okay, it’s kind of a love story. But only in a secondary, frustrating kind of way. Let me explain. I have always felt like I was “over” the story of Romeo and Juliet. Even the first time I heard the plot explained, when I was probably around ten years old, I thought it was kind of dumb. Romeo and Juliet kill themselves over a misunderstanding? Seriously? When I got older, and watched, among other productions, the lush Baz Lurhmann Romeo + Juliet, I liked it a little better. But it still rang hollow for me. I still hated the idea that people held it up as the greatest romance of all time. And I didn’t want to read it because it just seemed kind of silly. However, my Shakespeare class will be working on Romeo and Juliet, so this week, I actually read it for the first time. About half way through, I realized that I had been right: it is not the greatest love story of all time. It was never meant to be. But it is a very, very good play. A play that is so much more than the silly, passionate sob story it is misrepresented as. My first realization hit me about the time Romeo and Juliet decide to get married. This happens a little over a third of the way through the play, on the same night that Romeo and Juliet first meet. Now, Shakespeare sped the timetable up quite a bit on everything that happened in his plays, but even taking that into account, this is a pretty rash decision. Especially since the two households are on such bad terms, I kept thinking, “Wouldn’t it be a better idea to wait, and plan this out? Isn’t anyone going to tell these two that this is a really bad idea?” And then it hit me. That’s exactly what I’m supposed to be thinking at that point. Shakespeare didn’t mean for people to say, “What a great decision! Love conquers all! Yay Romeo and Juliet!” He wanted people to have my exact reaction--to realize that yes, this is a terrible decision. Romeo and Juliet’s passion is certainly legitimate, but rarely in any of Shakespeare’s plays does “love at first sight” hold much weight. Rosalind and Orlando spend weeks in the forest getting to know each other. Viola and Orsino are in close companionship for a long time while love blooms. Benedick and Beatrice spar and jest and flirt for years. It’s true, some of Shakespeare’s more minor couples do get together after a quick glance (Miranda and Ferdinand, Hero and Claudio) but by and large, love takes time in Shakespeare (and in the case of Miranda and Ferdinand, Miranda has a wise father who counsels them to take time to get to know each other before getting hitched.) So when Romeo and Juliet suddenly, rashly decide to get married the very next day, I don’t think it was intended as a triumph of love. I think it was a chance for the audience to ask, “Where are these kids’ parents??” And that is what the play is about. It’s about what happens when the guidance that should be there, isn’t. It’s about the consequences of a family’s decisions on the younger, less wise members. It’s about a girl and a boy who can’t talk to their parents. That is why this play is beautiful, and horrible, and important. Not because of the fervent but misguided romance of Romeo and Juliet. Because no one is there to stop it. Both Romeo and Juliet are smart and courageous, and very likable. But Juliet, we’re told, is not even fourteen yet. Romeo is probably older, but still very young. His youth is betrayed at the beginning of the play, when his storyline starts with him pining after Rosaline, only to switch his affections to Juliet when he sees her at the ball. The Friar, perhaps the only real source of wisdom in the play, chides him later for this sudden switch. But neither the Friar, nor Juliet’s nurse--the only two people who know what’s going on between Romeo and Juliet--have any real authority over the two lovers. They both try to dissuade them, but the nurse is so ineffectual that Juliet just laughs off her advice, and the Friar is likewise ignored. And though he gives good advice, by the end he is as cowardly as any, and leaves Juliet in the crypt to stab herself. What struck me most was the tone of the love scenes. Shakespeare was still quite young when he wrote the play, and that youthful abandon--that whole-hearted passion--is abundant in the love scenes. They were all the more poignant for being so misguided; I felt that if the situation had been right, Romeo and Juliet could have been a beautiful power couple, with more eloquence and honesty than perhaps any other Shakespearean duo. But the love scenes are sandwiched between scenes of incredible violence--Romeo’s duel, Juliet’s confrontation with her parents--and ultimately end in the deaths of not just Romeo and Juliet themselves, but also Paris, who did nothing wrong but himself love Juliet. This is a love story gone all wrong, and not just because of the outside influences working on Romeo and Juliet. Because they themselves do not have the wisdom or the patience to deal with what is happening to them. The scene that most broke my heart was not the final death scene. We all know that’s coming from a mile away. What just killed me was the scene in which Juliet’s parents tell her she must marry Paris, and she, already married to Romeo, refuses. Juliet, pleading, begs her mother to hear her. Lady Capulet replies: “Talk not to me, for I’ll not speak a word./Do as thou wilt, for I have done with thee.” She exits. I cried. I can’t impose on the text what it doesn’t say, but it makes me wonder what kind of relationship Juliet had with her parents previous to the opening of the play. If neither her mother, nor certainly her father, will hear her passionate pleas to delay the marriage, we must suppose that they have no real relationship with her. And while we don’t get to see Romeo’s interactions with his parents, we must assume that since he goes to the Friar for advice and comfort (and has before, it is implied) his relationship with his parents is likewise not one of counsel or influence. Some people focus on the political morals in the play--the chastisement against feuding factions, the reminder to “make love, not war.” But I don’t think it’s quite as simple as that. Because Shakespeare was the great playwright that he was, we sell him short by pitting Romeo and Juliet against the other characters in the play. It’s not as simple as saying, “Romeo and Juliet were good, and they were slain by the hatred of their families.” Romeo and Juliet were very flawed, and very young and stupid, and they were slain by the lack of wisdom available to them. It is a political play, it is a romance (with some of the most beautiful poetry found in any play)--but most of all it is a cautionary story about what happens when parents fail their children. Fail them by nurturing hate, or by neglecting to cultivate a relationship in which they are imparting honesty and wisdom. The result, Shakespeare tells us, is a generation of beautiful souls wasted. ~Ruthie

0 Comments

I'm starting a new story and since I haven't had any exceptionally deep thoughts about womankind recently, I thought I'd post the first few pages. It's loosely based on the life of my great-grandmother Carmel, and I'm hoping this attempt takes since I've tried to write about her several times. Any comments are appreciated!

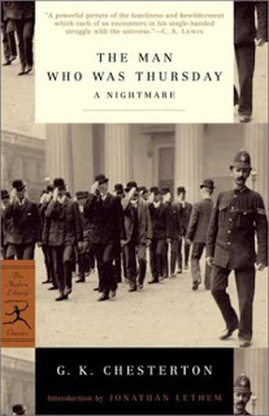

~Ruthie Carmel (excerpt) There was a new man in town. I heard it from Papa, who brought the tale from the men who leaned up against the posts by the schoolhouse and watched passersby. They weren’t as watchful as the men who lined up by the tavern, but they were more reliable because they didn’t drink except out of their hip flasks. And mostly their liquor was homemade, which Papa said worked out better for them in the end. This new man, I wanted to get a look at him because people didn’t come to stay very often in the hills. Way back when the land was settled, people thought the mountain where our farm lay was golden land, priceless. But farming ain’t what it used to be, I’ve heard Papa tell Mama. He stood by the stove in the wintertime when he was bit through with frost and went on about the cursed land, cursed right down from the time of Adam. I believed him that the land was cursed, but I think maybe it didn’t have anything to do with Adam. I think maybe it was just because of Papa. The week before the new man came to town, I lay awake in my bed until I couldn’t see the moon in the sky anymore, and still Papa didn’t come home. Not until the chickens were beginning to stir in their coop did I hear the steady tread of the mare’s hooves on the road up the hill, and then I heard the front door open, because Mama had been wakeful all night, waiting for him. My heart sank into my toes, which were wiggling in the early breeze atop the covers, and I knew that no matter what Papa swore, over and over, even if he stacked up Bibles till they tipped over and clattered to the floor, he would never get free of the bottle. I lay still and cold as I heard Mama’s voice rise hushed over the early light, even though we hadn’t got neighbors anywhere close by, and nobody was going to hear my Papa riding home drunk. But Mama kept her voice down, and I watched the sloping profiles of my sisters as they lay sleeping beside me. She was doing it for them, because Stella and Ruby still thought Papa got sick in the night. I wished I still believed that, and for a moment I listened tightly to the sounds, imagining that he was just sick. Mama’s gentle grunts as she lifted him from the horse, Papa’s sudden, sodden words, the accidental slam of the door, shuffling across the floor and a creak as Papa dropped into bed. That’s right, he was just sick. Poor Papa, getting sick like that. There was silence for a few minutes, and my eyes rolled over the planks in the ceiling above my head as I wondered what my Mama was doing. And then her soft footsteps crept through to the door, and I could hear the clink of the bridle as she went to stable Annabelle. Faithful horse, bringing Papa home. I felt my blood heat and my eyes clench tight shut, waiting for the sweep of rage to pass me by on its way through my body. My little sister Ruby probably would have prayed for deliverance from the anger, but I wasn’t about to let it go. I was holding on as tight as I could, because I knew what kind of help it could give. The kind of help my Mama didn’t have, because she couldn’t summon enough anger to cure my Papa. But Papa was better the next week. When he told my Mama the news, he cast a look in her direction that told me he hadn’t been hanging around the wrong side of the street, and then he let it out about Harry by the schoolhouse, and Mama smiled at him. I piped up quickly, easing up my fingers on the spoon I held. “What kind of man is he, Pa?” I asked. Papa fixed me with his brown eyes and shook his head. “Don’t know yet. Men say he’s in town looking for work, but there ain’t much round here to keep a man.” “Is he young, then?” I asked. I glanced at Elsie, but she sat eating silently. Papa nodded. “About all I know of him. From somewhere north, maybe Cuttersville. What he’s doing here I couldn’t say.” The information barely registered before I looked again at Elsie. My older sister was approaching twenty years of age, and in the hills that was too old for a girl to be unwed. I made a note to speak with her later and pressed my Papa further. “What’s he look like?” Papa shook his head again. “Quit your questions, girl, I ain’t never seen the man.” He said it hard, but I saw the twinkle in his eye. He knew I’d got the anger in my blood, and he knew it would keep me warm. He was proud of that. I let my mind pass over Papa’s news as I was doing up the dishes afterwards, and my Mama clicked her tongue at me. She couldn’t abide to see my hands idle. When the water in the bucket had started to grow cold I finished wiping up as quickly as I could, but when I turned around, Mama was looking at me with her hands on her hips. “You asked an awful lot of questions about that young man, Carmel,” she said. I laughed. “Well someone’s got to marry Elsie.” Mama came closer to me, and I thought for a moment she was going to put her hand on my arm. But then she passed me and picked up the dishtowel, and I saw that she was just going to give the table another wipe. She was silent, and I felt anger bubbling below my bellybutton, because she never spoke what was on her mind. But I was fifteen, and I knew better than to let my words out when they weren’t needed. So I bit them down and then I was out the back door, into the yard where the chickens Ruby was herding let out cackles of dismay at my fast feet. “Where you going?” Ruby called after me, but I didn’t answer her. She could figure it out, if she wanted. Probably everyone knew by then where I went when I wanted to be alone. My steps took off up the line of trees, pattering softly because I wouldn’t wear the boots Mama told me I should. Behind me the white clapboard house stood soft against the brush of trees surrounding it, and to my right the fields stretched out over the gentle slopes of North Carolina hills. But ahead of me, up the mountain, the ridge of trees that separated one field from another stood like a line of schoolboys paying attention, and I cut through them and ran headlong into the waving grass on the southern slope of the hills. That ridge was too steep to grow anything but grass for the cows, and I gave them a wide berth as they crop steadily. Our cows paid me no mind, unless I’d got Ginger with me. Then they laid back their ears and listened up. I used to hide in the trees along the ridge of that hill when Mama called for someone to help her bucket the water and bring it up to the house, or when Papa set us to bringing the cows down the slope. I didn’t hide much once I found my fifteenth birthday, but I still set off up there when I wanted to be alone with my thoughts. And my thoughts that day were all for my sister Elsie. I knew why she didn’t want to speak about another man. I’d seen her down behind the smokehouse, making eyes with George, the man who’d been working on the farm for almost six years. That included his time in the service, when he went off and fought in the war and came back with bad breathing and a hitch in his walk. The winter before, just after he’d come home and I was taking him some soup, he showed me the scars along the side of his neck where he’d clawed at himself in a frenzy because he couldn’t breathe. I asked him what it felt like when the gas leaked through his mask. “Like I’d swallowed liquid fire,” he said. “Like my throat was coming apart in pieces and hurrying up to come out through my nose.” I wrinkled my own nose, but I wasn’t scared by his words. I was never afraid to talk about what people felt in their bodies. When Stella was born I watched the whole thing, and stood by with the scissors the doctor had sterilized to cut the birth cord. But Elsie wasn’t like me. She was more like Mama, and when she heard George talking to me her eyes filled up with tears and she turned to the window to wipe them where George couldn’t see. He saw, though, and his face got all concerned. “Wasn’t so bad, Elsie,” he said. “They took me right away to the field hospital, and I ain’t none the worse for it.” He was right. He was only lying in bed because Mama and Elsie told him to, and he was up and working again the next day. He limped and his voice came out in a thin little rasp, but he was just as strong as he was before he left. And I knew something else. He’d always been in love with Elsie, always. Before he went away to fight the Germans he used to watch Elsie from across the yard, or over the dinner table. Ever since his parents sent him to work he’d been watching Elsie and wishing she’d watch him too. I reached the top of the ridge and lay down flat on my belly to watch the farm. The light was turning purple around the edges of the sky, and I could feel the chill breeze of early summer begin to dust up with the fading light. Maybe rain, too, though there weren’t clouds up yet. I could smell something on the air, and I knew the feel of rain when it came. Papa would probably be getting the cows in early, penning them up before one of us had to wade through the running hills. The barn door was open, and as if I’d conjured him up with my thoughts like a circus man, George walked out into the yard. He was with Walter, my older brother, and though he wasn’t but seventeen he’d got the walk of a man. My Mama didn’t know it, but I’d seen him hanging around by the schoolhouse with his friends, and I knew it wasn’t but a few steps from there to the public house and if he started down that road, there’d be no coming back. Just like Papa. But I liked to see Walter with George because George didn’t drink nothing. Maybe because the only thing he ever thought about was Elsie. My mind moved back to the things I heard them saying behind the smokehouse, and I blushed a little when I remembered that George had taken her hand in his. Elsie blushed too, but she didn’t mind it. She liked it, I could tell. And that was when I realized that she’d been sweet with George for a while, and she wasn’t going to get any less sweet. I had run back up to the house and found Ruby, and we tried to make sense of the fact that all it took for George to win Elsie’s affection was a war injury. He was still the same George, except now he limped. And he had a nice voice before, kind of deep with a little ache to it when he was tired. “Maybe she just liked nursing him,” Ruby said, but I shook my head. “She only got to nurse him for one day,” I said. “He was up and working about the next day.” But I guess I could see the romance in being sweet on a man who got hurt during a war, and I shrugged. “You can’t tell Mama,” I said to Ruby. “She might not approve.” “Mama and Pa like George,” Ruby insisted. “They treat him like a son.” I thought about her words and twirled my braid against my cheek. “Think he could run his own farm?” I asked. “Walter likes him just as much as Mama and Pa, but I heard him talking about the gimp in his step and saying that he might never be able to own his own land.” Ruby was too young to have an opinion about this, and Mama soon called me downstairs to fetch her the bacon I was supposed to have brought back with me. But as I watched George and Walter I made up my mind that if Elsie didn’t take George, I would. Even if he did limp, he liked to laugh and he could tell good stories. And he didn’t drink. Tired of watching the tiny figures, I rolled over on my back and gazed up through the branches climbing over my head. Another thing about George I liked was that he could tell the name of any tree I could find. Even Papa didn’t know as many trees as George, and he said it was because his Granny used to take him through the forest and teach him the names of everything they saw. My smile faded a little as I thought about that. George’s granny could cause trouble for Elsie and George, even though she was dead. George’s granny was a Cherokee. I used to wish I had an Indian for a granny. I couldn’t remember either of my grannies, because my Papa’s mother died early on, and my Mama’s granny lived clear over the mountains in South Carolina. When George told us stories about his granny his voice always crept low and soft, and he didn’t speak of her when he was around my parents or any other grown-ups. It wasn’t until I was twelve that I understood why, and then I felt my welcome anger creeping up into my belly. What was so wrong with an Indian for a granny? If she could tell George the names of the trees and the difference between the wild herbs, I didn’t see what difference the color of her skin made. But I thought Mama and Papa might not mind if Elsie married him. It had been a long time ago that George’s grandfather married his Indian bride, and things were different. Even in Birch Pass, people were starting to change their ways. There were even strangers moving through town. I sat up quickly, because I remembered the reason I began to think about Elsie and George. The new man in town was a young man, Papa said. I began to think of all the reasons he might be in town, as I sat in the thickening dusk. He couldn’t be a schoolteacher, or we’d have all known it. Besides, we had a schoolteacher. He might have been looking to work in the general store, or one of the other shops, or even maybe open up his own business. But that didn’t seem likely, because if he had been enterprising he’d have gone to a bigger town where people needed lots of stores. Birch Pass barely kept the general store, feed store, tailor and tavern in business, and the hotel only had one bedroom right next to Mr. Wicker’s own room. He even let his cook go because she wasn’t cooking enough meals to keep herself. So he was hoping for work on one of the farms. I grinned lopsidedly, letting my breath out in a scoff. He couldn’t have been a very bright one, that young man. Most of the farms around the mountains were small enough for family to keep them, and it was too late in the year to help with the planting and too early to help with the harvest. Anybody with sense would know to go north to the farms in the valleys the stretched toward Shenandoah, or even a few miles east out of the toughest of the hills. Unless he had kin nearby, there wasn’t any reason to stay in our part of North Carolina. He might have kin around. I pulled my braid into my mouth and sucked on the end as I turned over this new thought. Maybe his Mama was dying, and he had twelve little brothers and sisters to care for. His Pa would be dead already, naturally, and he’d be the only man big enough to make enough money to support his family. Or maybe he had a young bride in a little cabin somewhere, and she was about to birth their first child, and their barn had burnt down with all their feed and livestock in it. He was bound to need some charity, but he was probably too proud, and he wouldn’t accept anything but good honest work. I smiled to myself and squinted into the deepening dusk. I couldn’t tell whether Walter and George were still in the yard, and I could just barely make out the edges of the barn in the thick of dark descending. The house, hidden behind a crop of trees, was lost to me. I thought about sitting up on the ridge until it was really dark, and waiting for Pa to come looking for me. If I sat still enough, he probably wouldn’t find me at all, and I could stay out all night and sleep under the stars like George’s grandma. Maybe I’d climb a tree and sleep curled up on a branch. But I’d tried to sleep in a tree, and I knew that it never worked out quite like I wanted it to. Before I knew it I was comparing the sharpness of the branches of a tree to the softness of my bed, and I stood up to brush my skirt off. Leave the stars to the Indians, and the trees to the birds. I wasn’t giving up my bed. I put my hands to my arms to brush away the goose bumps, and then I heard my mother’s voice rise over the hushing of the cicadas. “Car-mel,” she called, throwing her voice up into the hills, “Car-mel…” I started down the ridge toward her voice, and it seemed to me then that I was walking down out of the clarity of my thoughts into the reality of life—a thick web of it, up to my throat and smelly. But when I rounded the hill and saw the flicker of light in the windows, the feeling passed, or at least eased a little. Besides, my Mama was at the door, and she gave me a smile as I walked in. “First call,” she said. “Very kind of you.”  I recently read The Man Who Was Thursday. That book touched me very deeply, and I can’t stop thinking about it and the crazy, weird imagery that seems to make so much sense to me. But the content of the book is not actually what this post is about. Really what I want to talk about is the male to female ratio of the book. It’s a very skewed ratio, since there is only one female in the entire work. Not that there’s only one main female character—there is literally only one female mentioned throughout the entire book. Except for the sister who brackets the book by a few pages at the beginning and a sentence at the end, every character—supporting or main—is male. There’s not even a waitress or a flower-seller. It’s a little weird, actually. But I’m not writing this to complain about the lack of femininity in GK Chesterton’s book. What I really find interesting is the fact that I read this book over three days and until the afternoon after I finished it, I didn’t even notice that there were no women in the book. I, a woman, read an entire book, and loved it, and got a lot out of it, without even realizing that none of the characters shared this fundamental aspect of my identity. This does not seem to be a huge deal. There are plenty of books I love in which all the main characters are men. But what I think really interesting is this: if this had been the opposite situation, and a man was reading a book comprised of a completely female universe, I doubt he would have had the same kind of experience I did. I know there are lots of guys who like books about women. There are classic women writers like George Eliot and Emily Bronte who wrote about women, and men definitely read those books. There are even books like Sula by Toni Morrison that tell tales with lots of female characters, and men read and enjoy those. But honestly, how many books are out there that don’t have any main male characters? And of those books, how many men exist who would be chomping at the bit to read them? I’m not really saying that this is a good or a bad thing. It’s just interesting to note, and I’m wondering why this is. Is it because for centuries men have been the dominant writers, and women are just used to reading men’s books? Because it’s generally thought that men are more universally relatable than women? Is it some weird impact of feminism—because women tend to be more open to the idea that men and women are equal and on the same playing field, they accept the experiences of men as relatable ones? I have no idea why any of this is, and I’m really interested. I’d love to hear from some guys, in case I’ve totally misrepresented them and they would actually love to go read a book with all female characters. And I’d love to hear thoughts on this subject—if indeed I’m right. Why are women so much more ready to read man books? ~Ruthie This semester I took a class called ‘Acting Shakespeare,’ a class that I was incredibly intimidated by. The thought of memorizing Shakespeare weekly for an entire semester was very daunting, but once the class started I realized that the scariest thing about the class was not memorizing the words or understanding what the heck they meant; the biggest challenge was doing justice to the characters created by William Shakespeare. And I realized that Shakespeare knew women. Really, really knew them.

This was a surprise to me. Through my experience with Shakespeare before the class, I knew that many of his female characters had great lines. But after studying and scanning and getting up and speaking some of those lines, I found myself connecting on a whole new level with the women whose lines I was saying. It was while I was weeping before the class as Hermione, having felt something pull at me in her lines: How will this grieve you When you shall come to clearer knowledge that You thus have publish’d me. Gentle my lord, You scarce can right me throughly then, to say You did mistake that I was really sold on Shakespeare. Really, really sold. This guy has something to say to every situation. And he understood women. He understood them because he understood humans, probably, but that doesn’t make it any less impressive. Most of his female characters were smart as whips—many smarter than their male love-interests. And because Shakespeare had this understanding of women, he did what he could with them, and then when he needed a little more freedom he put a pair of pants on them and they paraded around the stage speaking as women in disguise. It’s their wit that makes them impressive, but it’s their struggles and their hearts that make them unforgettable. Shakespeare’s characters are so much more than the intellectual, hard-to-understand thees and thous people commonly think of. Even Juliet, the archetypal girlish lover is so much more than her swooning stigma. How beautiful are her words—spoken from an incredibly agile mind—when she says to Romeo, They are but beggars that can count their worth But my true love is grown to such excess I cannot sum up sum of half my wealth. I guess it’s that blend of strength and beauty that made me first fall in love with Shakespeare’s women, but there’s more. The situations he puts his characters in are so insightful. How did he know to write about Phoebe from As You Like It, and the more likable Olivia from Twelfth Night who are both proud and bored—how did he know that what they really want is just to be seen for who they truly are? Play Olivia as a woman who is beautiful and just wants to be praised, and she’s flat. Play her as a woman who is beautiful and has known only praise, and then is faced with a man who tells her that he’s not in love with her and calls her out for her pride—play her as that startled, intrigued woman and she breathes with life. Even if it means being told to their faces that they are “too proud,” women want to be seen. Shakespeare knew that. How did he know to write about Helena, the lover from A Midsummer Night’s Dream who is beautiful, and smart, and in love with a man who doesn’t love her? How did he know to give her a part where she knows she’s too good to be chasing after Demetrius, and yet does it anyway? How did he know to write about Rosalind, the brilliant leading lady of As You Like It who gets in over her head and then tortures the man she loves with her playmaking because she’s dressed as a man and can’t stand the pain their interactions cause? How did Shakespeare know that it never works out well to pretend to be something you’re not, and how did he bring his female leads to that beautiful conclusion in so many of his plays? There is poetry in Shakespeare’s plays, along with the wit. But it’s not the beauty of the words that makes Shakespeare’s work enduring. It’s the fact that he knew humans. He knew what they needed, and how they acted, and what they said and what they should have said. I’m convinced that my acting teacher is right—Shakespeare is not for English majors. It’s for actors. His work is worth reading and studying, but it was meant first to be seen on a stage. Of course an actor has to do the work of scanning and looking up words and figuring out what she’s saying. But if an actor truly knows her character, I’m convinced that Shakespeare’s plays will make more sense to the audience just by hearing her speak than if the audience spent hours studying the meaning of the text. I worked a lot on Hermione, the wronged queen from The Winter’s Tale. After reading the play, I still don’t know why she comes back to life, and whether there is some deeper meaning in the text. But from working on her as an actor, I have learned about her forgiveness, and her grief, and her constant dignity. Those things—and the things that I still can’t articulate about her but can feel within me—are the things I think Shakespeare meant us to remember about her. Those are the things that made him a brilliant playwright, and a frighteningly accurate observer of human behavior. So go watch some Shakespeare. Better yet, pull out a play, do the work of understanding the text, and then speak it out loud. Embody it. Figure out why the lines that are supposed to be iambic pentameter have an extra couple syllables. Shakespeare didn’t just make mistakes—he always had a reason. His women—and his men too—can tell you something about those reasons. ~Ruthie |

Currently Reading

Open and Unafraid David O. Taylor O Pioneers! Willa Cather Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|