Like most people, this summer completely overwhelmed me. It felt (and honestly still feels) like the world was tipping sideways, sliding toward a precipice of anger and confusion waiting to swallow us. The news is always bad; people are grieved and shocked and dying and selfish. In June, my friend RachelAnn told me about a podcast by a woman named Jen Wilkin, which is a recording of a study she led on the biblical books of Joshua and Judges. At the time, I was sold because RachelAnn mentioned that Wilkin spoke on the character of Rahab in a way that was different than any teaching she’d heard before. I, like a lot of women in the church, tend to think of the Old Testament as a bit of a barren wasteland for women--a place where the true heroes are the men, and the stories about women are mostly just those illustrating abuse or suffering. I couldn’t anticipate, at the time, how deeply this study would affect me. I didn’t know how it would not only completely upend my perspective on the amount of time and attention given to women in the Old Testament, but also transform my anxiety about the world. The one thing--the only thing, I think--that could reach me in a place of true grief over the state of the world and the state of my own heart was a careful study of wickedness, and the God who moved the authors of Joshua and Judges to record it. I began with Joshua, and true to RachelAnn’s words, I was struck by the story of Rahab and her courage and faith. It’s been years since I read this book, and I felt as if I was reading it with new eyes. This post is partly an encouragement to listen to Jen Wilkin’s study, because it’s extremely thorough in scholarship and timely in its nature, but it’s also just a reminder that all of scripture is precious. I admit that I spend the bulk of my time in the epistles and the gospels, but after living in Joshua for eleven episodes, I am hungry now for the words of the Old Testament. The care God took with the Israelites as he brought them into the promised land, the way the stories are recorded, and the steadfastness of God’s promises are life in a time when we are all feeling uncertain and, to be honest, a little abandoned. Patience is probably my least present virtue, and to read about the many times God had his people wait, and wait, and wait was both crushing and freeing to me. But really, the book of Joshua felt like a warm up to the book of Judges. It was important in content and context, but when I began the episodes on Judges I felt the true surgery begin. This book is both beautiful and horrible. It tells of a people who are constantly doing “what is right in their own eyes,” with no true leadership and no desire for the good of others. For large chunks of the book God is silent, allowing events to unfold. I felt my heart resonate with the squandered land, the injustices, the exploitation. It all seemed so familiar. In her lectures, Wilkin kept saying, “If you want to know how the Israelites are doing, look at the women. How are the vulnerable being treated?” She guided us through the beginning of the book, where women have the status to negotiate for what they want (the story of Aksah), places of leadership (Deborah, who also presents qualities of God in such a way that she points to the character of Christ) and the ability to fight for those less capable (Jael). But by the end of the story we are seeing a people who have begun to abuse the vulnerable (as in the truly horrible story of the Levite’s concubine) and care so little about the value or interests of women that they give their blessing to the abduction and rape of hundreds (the wives of Benjamin.) I knew these stories; I had read them before. But they always seemed disjointed. Now, with the background from the study of Joshua, and Wilkin’s careful contextual analysis, they were transformative. I went to see Rachael Denhollander (the first accuser of convicted sexual offender Larry Nassar) speak last Spring, and her talk was all about how important it was when she came to truly believe that justice and forgiveness are inextricable, and that it was through her study of the Old Testament that she found healing in the fact that God is a God of justice. I didn’t understand it at the time, but I think I can understand a piece of that now, even though I have not gone through what she has gone through. There is a simmering anger I feel, and I think a lot of us feel, at the continual abuse of women, and of people of color, and of the marginalized, and the only way I know to find peace from the anger is by seeing that God cares even more about it than I do. There were a million personal applications along the way that made the Joshua and Judges study especially helpful for me, but the overarching message is this: God is not overwhelmed by evil, even though we are. And through the many stories about women that are found in Judges (and now I recognize, are found in the entire Old Testament) he is showing us that he sees. When I cry out in my spirit about the endlessness of pain and the triumph of evil, the book of Judges is saying, “He sees.” He does not always help in this world, which is hard for me to understand, but he always sees, and it always matters. And he will always have the last word. Wilkin ended her study by referencing the book of Ruth, which ironically, although Ruth is my namesake, has always sort of mystified me. It seemed like such an odd little book to be placed right between the chaos of Judges and 1 Samuel. But when I read it with fresh eyes full of context, I just cried. It’s so clear to me now why it’s there--right there, immediately following some of the worst evil found in the scriptures. Because in it, as Wilkin reminds her listeners, we see a picture of sacrificial love from both Ruth and Boaz, a story of courage and tenderness and selflessness, that is so deeply in contrast to the stories we just read. Ruth, like Boaz, points to the character of Christ, and through their descendents God brought about the birth of the savior that is the true triumph over the chaos we still feel. Most remarkably, Wilkin points out that the story of Ruth runs concurrent to the rest of the book of Judges--not after it, but at the same time. While all this chaos is happening, while women and the vulnerable are being abused, while people are taking what they can and rejoicing in the suffering of their enemies, God is faithfully, quietly at work. That is a true hope to cling to, and one that has radically altered my feelings about the world I live in right now. We do not control the hearts of our fellow people, and most of the time we can’t even do much to fix the horrible things that have been done. But we have the courage to continue to live and to work because God has never abandoned his people, and he never will.

0 Comments

Maybe it's because for the past few months I've been in such an uncertain period of my life, but I've recently been thinking quite a bit about joy. Unlike happiness, which is something that cannot be called upon or chosen, joy is something that we can, in fact, choose to have.

That reality has always kind of confounded me. Because my understanding of joy is usually a false one (mixed up with the idea that it is the same thing as happiness) I've always viewed verses that discuss choosing to have joy, or being overcome with joy, as quite difficult. I want someone to just tell me exactly what it means to choose joy. Joy is slippery, because it must be sincere, but it is also a clear decision. In addition, the Bible not only encourages us to be joyful, it commands us. One passage that has been a stronghold for me for many years is this one from Romans 12:12: Be joyful in hope, patient in affliction, faithful in prayer. (NIV) I don't know exactly what it means to be "joyful in hope," but I know that I'm commanded to do it. And as with so many other things, that is a good place to start. CS Lewis wrote a whole book that told the story of his journey to joy, called, appropriately, Surprised by Joy. In it, he discusses the ambiguous nature of joy, and explains what he thinks joy is: Joy (in my sense) has indeed one characteristic, and one only, in common with [happiness and pleasure]; the fact that anyone who has experienced it will want it again... I doubt whether anyone who has tasted it would ever, if both were in his power, exchange it for all the pleasures in the world. But then Joy is never in our power and Pleasure often is. And later on Lewis writes: All Joy reminds. It is never a possession, always a desire for something longer ago or further away or still "about to be." In Lewis's opinion, then, joy is something just out of our reach, something that we receive only when in communion with God. And yet we are clearly commanded, throughout the Bible, to rejoice, as in Philippians 4:4: Rejoice in the Lord always. I will say it again: Rejoice! (NIV) So what does it mean to choose joy? How do we separate joy from the health and wealth gospels and the wrongness of expecting Christianity to bring prosperity and happiness? I think it has to do with the first verse I quoted. Being joyful in hope points to the fact that this is not something we can pull from inside ourselves, or manufacture. It is a constant choice to call ourselves back to the truth of hope--a reminder to fix our eyes on the grace and promises of Jesus. On a super practical level, it probably means reciting the words of the gospel to myself, meditating on the work of Jesus, speaking with God. It means questioning my motivations and assumptions, and forcing myself to weigh my words and my thoughts before sliding to extremes. In this season of life, it means being grateful for the blessings poured out on me, and being patient in the uncertainty. It means trusting in God's provision, and not being cynical about my dreams. It means being faithful to wait, and pray, and cry maybe, and not giving in to the frustration of constantly being in a state of uncertainty. The times in my life when I have had the deepest awareness of both the fragility and the beauty of life are when I've had to wait, and be joyful in hope. Especially during this season of Advent, let us rejoice in the goodness of a God who commands us to pursue something so very good for us. ~Ruthie This past weekend I took a class called “Exploring Social Issues Through Drama.” As part of the class, we each chose a social issue to explore. I chose objectification of women, inspired by a female friend who told me about harassment she’d experienced that week. While on a packed train, a man took advantage of the situation and aggressively pressed himself against her. She didn’t say anything, just moved away, frightened she would only escalate the situation. No one on the train did or said anything. With her story heavy on my heart, I used the class time to explore this topic and how it affects all women, whether we realize it or not.

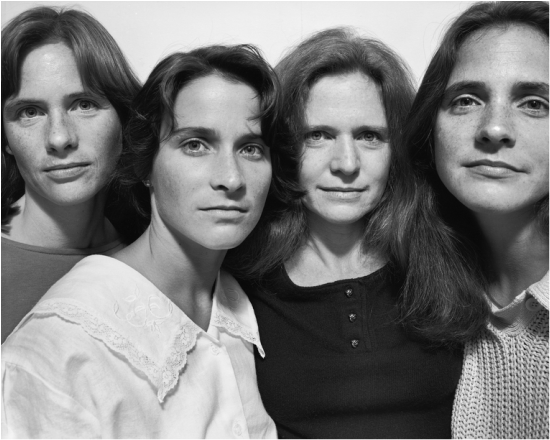

Ironically, this is the week that the photo of Kim Kardashian’s bare butt debuted, displaying quite clearly to the world that controversy is deeply imbedded in this issue. It should come as no surprise that women (and men) everywhere feel the need to address the photo shoot. And while talking about it is of course exactly what Kardashian intended, the issue has to be discussed. We are, as a culture, silent bystanders, watching a metaphorical (and all too real) sexual assault on the subway. It’s time to talk about it. The facets of the issue are endless. Leaving aside for now the question of photoshop (related to objectification) and the disturbing connections to racism and sexism in photographer Jean-Paul Goode’s work and personal life, the question of objectification of the female body rises up front and center. What should be quite obvious is that Kardashian herself is the one doing the objectifying. Yes, she is part of a culture that puts immense pressure on women to buy into the role of sexual plaything, and yes she is responding to societal demand. But when it comes down to it, she is the one that took off her clothes. I’ve realized recently that one of the biggest problems with the feminist movement is that it means so many different things to different people. There are many tenets of feminism that I identify with, and simply because I am a woman and care about women’s issues, I recognize that I can and should call myself a feminist. But there are also feminists who bare their butts on the covers of magazines, and pass it off as a step toward less body-shaming or toward sexual freedom. While I’ve never heard Kardashian explicitly call herself a feminist, women like Scout Willis and Chelsea Handler seem to be constantly on Instagram crusades to allow topless photos, and Beyonce has certainly identified quite strongly with the movement. (Though it gets sticky talking about Queen Bey, because that conversation tends to get intermixed with discussions of race and cultural expectations.) The issue became crystal clear to me while talking with my brother, who I called during a break from my social issues class. I asked him what his response was to the feminist movement, and he replied, “Well, it depends on what you mean by that.” As we talked he expressed confusion about the stances of women; he felt he supported many of the arguments, but was unsure about many of the intentions and affiliations within the idea of feminism. Because there were so many voices with such divergent views, he was hesitant to claim the banner of feminism as something he could completely stand under. In talking with my roommate, the matter became even more tricky. As a woman who works at a pub in midtown Manhattan, she is constantly being objectified, being told: “Come over here baby so I can grab that ass.” But her words gave me pause when she began to talk about how women treat themselves. She described the outfits girls wear on Halloween, and how they’re clearly expecting men to look at them in a sexual way on that night. “Girls want to be cute and sexy on Halloween, but then they want to walk down the street the next day and not get any comments. It’s like they want to be selectively objectified,” my roommate said. I want to tread lightly here, because I do not mean to suggest that women should feel obliged to hide their bodies, or that they bear the responsibility of keeping men in line. And I certainly don’t want anyone to think a woman is ever “asking for it,” or any of the other justifications used for objectification, sexism and violence. But both my brother’s and my roommate’s comments have something pertinent to offer this messy business of Kim Kardashian’s butt (and boobs, apparently. If you buy the magazine and flip to the inside.) How seriously would you take a man who exposed himself on the cover of a magazine?* I think this is an important thing to think about. I believe that bodies are beautiful and we should be proud of them, but there’s a cultural precedent built into society that indicates that it’s okay to display the female body for the delight of men. Kardashian’s photos support this flawed view, to say nothing of the dangers of the photoshopping involved in the photo. As much as I hate to say it, those who desire change have to—at least somewhat—play by the rules of the dominant culture. There is a balance to be struck between stirring the pot and allowing people time and incentive to change their minds, and that change has to come from the heart. Just as guilt and shame are horrible motivators, rage and defiance don’t work either. If we are to build a culture in which men stop making comments about my “titties” on the street, and in which women feel their voices are heard and respected, women have got to stop playing into the stereotypes. Kim Kardashian is not desperate—she’s not trying to make a living or a name for herself and being forced to use whatever means she can. She has an incredible amount of money and power, and a platform to say whatever she wants. Until women like her stop objectifying themselves, we are going to keep having these same conversations, over and over. ~Ruthie *Which, by the way, has happened—as is evident from articles such as this one. I need to note here that this isn’t exclusive to women, and men are playing into their stereotypes as well. It’s just far more common for women. Nicholas Nixon began taking photos of his wife and her three sisters in 1975, and has taken a photo every year since. The result is incredible.

"Throughout this series, we watch these women age, undergoing life’s most humbling experience. While many of us can, when pressed, name things we are grateful to Time for bestowing upon us, the lines bracketing our mouths and the loosening of our skin are not among them. So while a part of the spirit sinks at the slow appearance of these women’s jowls, another part is lifted: They are not undone by it." -Susan Minot, writing for the New York Times This photography project is one of the simplest and most beautiful I have seen in a long time. As we click through these photos, we see, gently and gradually, what it means to be a woman, a sister, a human. As the lines on these women's faces slowly deepen, it's tempting to read into them--to wonder what experiences have shaped them, how each sister differs from the others, and the story of each photograph. But while the four women have allowed us a glimpse of their faces each year, that is all they have allowed us. Their openness--close bed-fellows with their privacy--makes this project remarkable, poignant, and beautiful. Check out the photos and New York Times article here. ~Ruthie I don’t know if it’s the fact that I’m getting older, or if there’s something specific to the way NYC has been shaping me, but I’ve recently been thinking a lot about being able to just be who I am. At this point, while I will always continue to change and grow, I am settling into the woman I am and the way I’ve been shaped. The process of questioning myself doesn’t end, but there are some things I know, and I want to have the ability to just be.

Specifically, I’ve been thinking about this in relation to art, and to being a Christian. I am much less worried about being a Christian than I have ever been before in my life, and that strikes me as encouraging and also kind of embarrassing. This is who I am, and yet for most of my life (and there are still many moments) I’ve been worried about how people will treat me, or what they’ll think, or how they might misperceive my beliefs. But I’m starting to believe deep in my core that it’s okay to just be. I am a Christian. It’s who I am. It’s okay. And I am an artist. This post is about why I am starting to question the label “Christian artist.” This is not the first time I’ve questioned it, but it’s the first time I’m putting it into words. Questions about it have crossed my mind several times recently, most recently when I came across this article about Switchfoot and their contention of the label “Christian band.” (I know this is an old article. But hey, I’ve been busy.) When asked if they are a Christian band, their lead singer, Jon Foreman, says: "To be honest, this question grieves me because I feel that it represents a much bigger issue than simply a couple SF tunes. In true Socratic form, let me ask you a few questions: Does Lewis or Tolkien mention Christ in any of their fictional series? Are Bach’s sonata’s Christian? What is more Christ-like, feeding the poor, making furniture, cleaning bathrooms, or painting a sunset? There is a schism between the sacred and the secular in all of our modern minds. The view that a pastor is more ‘Christian’ than a girls volleyball coach is flawed and heretical. The stance that a worship leader is more spiritual than a janitor is condescending and flawed." I don’t think there’s anything wrong with calling oneself a Christian artist. But I agree with Foreman that there are certain unfair expectations that arise with the label. Like erroneously expecting a pastor to be more pure than his congregation, expecting an artist who is a Christian to only ever create art specifically referencing Christ is severely limiting. Would you expect a bank teller to make a Jesus reference to every customer who comes up to his booth? Or a journalist to work a Biblical narrative into each byline? And yet Christians who are artists are often unfairly expected to reference Christ in every piece of work they create. The genesis of this, I believe, is complicated. I would argue that it is partly cultural, and partly theological. Culturally speaking, it’s closely tied to the fact that in many parts of the West, and certainly in the United States, the cultural consciousness surrounding art is unhealthy. I’ve written about this before, but because art is considered a luxury, only as good as its entertainment value, and primarily an industry--not as a way to share stories and therefore an integral part of life--artists tend to feel the need to heavily justify their decisions to be artists, whether in a monetary sense or otherwise. Theologically, the matter is complicated by the fact that most art in the West during the Middle Ages revolved around the church. In addition, during the Reformation Christians developed the idea that any kind of art during worship needed to be heavily justified, and as art became more important outside of the church, this trickled down into art outside of worship as well. Today, these cultural and theological pressures often take the shape of artists telling their Christian friends that they are pursuing art so that they can either “bear witness in a secular industry,” or use their art as a platform for proclaiming the name of Jesus. Neither of which is a bad thing. But, I would argue, neither of which should be the primary goal in being an artist. As Christians, we are called to bear witness first and foremost in every aspect of our lives. That is certain. But that is true for every Christian, no matter what profession, and it does not always take the form of explicitly naming the name. In some fields, like my father’s field as a physicist, it never does. The great thing about art is that it can take that form. But it doesn’t have to. There is no need to justify a career in the arts any more than to justify a career in plumbing. Art is inherent to humans, and storytelling begins as soon as speech does. As Christians, sometimes we speak in our daily life about how much we love Jesus, and sometimes we speak about how much we love coffee. Artists should be free to speak about either as well. And really, there is a lot of laziness that has come about because of the concept of “Christian artists.” There are many beautiful pieces of sacred art, or stories about Christian experiences that are heartfelt and important. The Biblical narrative is woven through all of us, as Christians, and it should come out of our pores. But there are also plenty of pieces of horribly lazy art and stories with the name of Jesus plastered on simply because there is a market for it. Artists who are Christians cannot be lazy. They cannot rely on a market, as many have. It’s much more difficult to tell a diversity of stories, some of which specifically name Jesus, and some of which don’t, and it’s difficult to interact at all times with a world that holds different beliefs and values and find ways to create and converse with artists outside the Christian faith. But it’s important. It’s a command, to all believers. In the same way, Christians who are not artists must refuse to be lazy as well. It’s much easier to rely on a Christian label or art industry to provide entertainment and enjoyment, for us and for our kids. But we are called to engage in the world, and to feel the pulse of its heart. Doing the work of evaluating art--by artists who are both Christian and not--is important. Some of it you’ll have to throw away. Some of it will touch you deeply. And that’s good. The bottom line is that we are Christians first, and that changes the way we think, speak and breathe. But once it gets into our blood and marrow, we as artists don’t need to be constantly questioning our profession. We fix our eyes on Jesus, and trust in the process of sanctification. Sometimes that means we’ll create art that speaks intimately of Christ’s sacrifice for us, and sometimes it means we’ll write a comedy sketch about the bus stop. Whatever project we’re working on, let’s not be afraid to just be. ~Ruthie *My brother Daniel recommended a book called Art and the Bible by Francis Shaeffer to me recently, which apparently speaks directly to this. Worth checking out!  Women Arriving at the Tomb - by He Qi Women Arriving at the Tomb - by He Qi Friday is moaning and Sunday is laughing, but Saturday is silence. I breathe the deep stillness of both the cross and the empty tomb, but the disciples and the women knew only the pit of having had Him and being left with nothing, and silence weightier than existence, that broke the earth and rewrote it backwards and forwards. Silence that fills lower and higher-- pouring out of a sepulcher that calls forth my adoring wonder. (Last two lines inspired by The Valley of Vision) I don’t really make New Year’s resolutions, but this year, since January, I have been giving a lot of attention to the cynicism present in my heart and my mind. At first, I was startled by its very presence. I have always considered myself an optimist, attuned to the thoughts and feelings of others. There should be no room for cynicism in my heart, especially as I continue to grow deeper in my faith.

But of course, this is not the case. As I have been observing, my heart is steeped in cynicism and fear. Over the past few months I have noted this with dismay, marking the crippling outworking of it in my life. I tell myself that whatever it is that I want, I won’t receive it or it won’t come to pass, because good things just don’t happen to me. I don’t walk in the rosy light that so many seem to walk in. I struggle. Even a snapshot look at my life should reveal to me how ridiculous this is, but it doesn’t. Today my pastor preached on greed, and Matthew 25, speaking to us about money. Such a touchy subject, but one that Christians have to hear, and I felt my recent convictions about cynicism stirring in my heart, because I think my cynicism is often just a mask for selfishness. Especially when it comes to money, but really in everything, I truly own nothing. Everything has been given to me, and yet in my heart I deeply believe that I am entitled to what I think I need. On my birthday, a few weeks ago, I jokingly told my family that this was my name-it-and-claim-it year. As I get older, and figure out what I want, I want to know that what I want will happen. That I’ll be taken care of. I don’t want to be rich. I’ve never wanted to be rich. I just want to be comfortable. I don’t want the best job. I just want a job with health insurance, where I feel that I’m using my talents and skills. I don’t need a month in the Mediterranean every year. I just want a few weeks to dip my toes into the ocean. And these are not bad desires. Comfort and security often lead people to a place where they can be loving and useful to others, and where their skills are truly used for good. But my absurd cynicism rears its head and makes these desires more important than they should be. My cynicism is born out of selfishness, but it’s also born out of fear. It’s a way of buffering my heart against failures. If I care too deeply, or want something too badly, I will be hurt when it’s not given to me. But if I cynically tell myself not to get my hopes up, I won’t feel the sting when it doesn’t pan out. I live in my crippled shell of fear, with selfishness textured in, because I don’t understand that every moment of breath is a gift. My pastor described God as a billionaire taking fistfuls of money out of his pockets and throwing it at people. We live in the midst of the incredible gifts thrown at us--and I don’t mean the money or the comfort or the security. I mean the way the train runs around a bend and comes to a stop in front of me, and the yellow daffodils nodding at me on the kitchen table, and the glancing eye-contact I shared with a woman I passed on the street yesterday, and the heavenly smell of coffee brewed on a rainy morning. We live among splendor, every moment of it rubbing up against pain, and the tension of holding the sorrow of the world in one hand has to be balanced by the joy of holding the beauty of it in the other. I don’t want to imprison myself in a shell of cynicism. I don’t want to be afraid to trust, and to love, and to risk. I want to give generously, of my money, and my time, and my prayers, and my love, even if it’s not reciprocated, as hard as that is. God has given me common sense so that I don’t squander my gifts, but he’s also given me a world to explore and to love, and to help. He has given me so many good things, and there is no time for selfishness or fear or cynicism. My acting teacher Mark Lewis used to say: “Everyone should have their heart broken, and break someone else’s heart. At least once.” We are obsessed with safety, especially the safety of our hearts. We pack ourselves in so tightly that we can only ever look forward to the next thing, because maybe it will be more satisfying than the hollow isolation of the present. It doesn’t make sense, and it doesn’t make us any safer, and it’s certainly not Biblical. So this year I am resolved to continue to watch my heart, to pray that my cynicism is slowly carved out of it, and to open my eyes to the momentary blessing of each day. ~Ruthie Whatever your stance on the issue, this post by my friend Courtney is worth reading. She's not interested in yelling or arguing. She just shares her honest, beautiful story of anorexia, pregnancy, and, ultimately, love.

Take a look at Courtney's eloquent words. ~Ruthie Thank you for the curve of my legs--

I like them. Also thank you for my ingrown hairs, even though they’re gross. Thank you for fingers that have wrinkles on them-- nobody else’s wrinkles, and I can slap and eat and touch with them. Thank you for my round eyes and my achy inner ears, and the bump on my nose. Thank you for my hair, because it’s beautiful-- and even when it’s not, thank you. Thank you for the jagged, fisted cramps that keep me awake once a month, not just because they remind me how good notpain is, but because they are mine, and only mine, and this whole body is mine alone: Mine. Given to me mine, mine as a mystery: body, mind, soul. And when I’m gasping or retching or bitching Here I am in the body, and the mind, and the soul that was created as me. ~Ruthie  We are a society of all types of women. We are old and we are young, we are short and we are tall, we are big and we are small. Supposedly, we are all beautiful. But as I think more about older women, and the way we live in relation to one another--and particularly as I live my American media and culture infused life--I know, as we all know, that this message is not the one we believe. And our fixation on beauty (or our lack of beauty) often results in the fact that we don’t realize how influential our own actions are. Especially as we relate to each other. So what I want to say is this: Mothers should tell their daughters that they--the mothers--think they themselves are beautiful. This might be a shocking idea, especially in the Christian subculture where modesty is a hot topic and false modesty abounds. Plus, beauty itself is a tricky subject, because the question, “What is beauty,” is so slippery. No one denies that most of us have built in triggers that go off when certain physical characteristics appear. However, there’s also no denying that love transforms the beauty of the beloved--and not just in the way of forgetting physical flaws. As love deepens, a lover often begins to truly see their beloved as physically beautiful, even if he or she is not a great beauty. The same goes for familial love. Beauty, I believe, is a combination of body and soul. But back to the issue at hand. My own mother, like every woman, has her own insecurities. But I have no memory of her discussing her personal appearance as I grew up. I never heard her complain about her weight, or wish for a different hair color, or talk about another woman’s beauty relative to her own. It’s only now that I am an adult myself that she has started sharing her insecurities with me. I am only just beginning to understand how priceless a gift she gave me. Until I reached high school I had a minimal amount of body-related angst. I wanted to look pretty, and I coveted and longed for my friends’ clothing and accessories. But the thought that my body might not be good enough did not occur to me until I was well into puberty. I’ve never really thanked my mother for this. I’m not even sure she did it intentionally. But I know that it was huge. And I believe that as women, and as Christians, we can take this one step further. We can tell our daughters that they are beautiful, surely. But we can also tell them that we are beautiful. As with everything, this requires thought and wisdom. A longing for and appreciation of beauty can easily become vanity. This was a timeless moral until the 20th century, when the pop world went crazy and we all became inundated with hundreds of images a day. So something that would have perhaps seemed incredibly selfish a hundred years ago--proclaiming one’s own beauty--has become a matter of importance. Let me explain. When I was a little girl, I believed that my mother was beautiful. Truly, absolutely beautiful. She was strong and protective and wise, and to me, she was perfect. She was my mother. If she had told me she was not beautiful--if she had complained about her body, and had let me see that her imperfections were unacceptable--I would have been devastated. And then I would have had to ask, “Well, who is beautiful, then?” When little girls aren’t allowed to believe that their mother is beautiful, the search leads them to the unreal expectations we all face as teenagers and grown women. But if, instead, mothers decided to put aside the disappointment of extra weight and sagging skin, and instead told their daughters, “Yes, it’s true--I am beautiful,” those little girls might have an extra couple of years to soak up the idea that beauty is more than just what they see on a magazine cover. And by the time they entered middle school and high school, maybe they would have at least this one thought in the backs of their minds: “My mother thinks she’s beautiful. And so do I. And if she truly thinks that, maybe beauty isn’t what I’m being told. Maybe it means something much deeper and wider.” Of course, this presupposes that mothers are discussing beauty with their daughters in all of its fullness--that our beauty is riddled with imperfections and yet we are grateful for the bodies that give breath to our spirits. Perhaps real beauty lies in this idea: that though our bodies are so imperfect, they are our bodies. And because we are not just given bodies to wait out the time until we can fly off and become disembodied souls (thank you Wheaton for helping me understand the heresy of Gnosticism...) we should rejoice in the bodies God has given us. Be they broken, or whole. This doesn’t mean physical beauty is all equal. We have eyes. But physical beauty is much more than our culture leads us to believe. Especially when we look at our bodies through the lens of people who are whole, and not just souls trapped inside flesh. I may not have my neighbor’s hair, but it is my hair. And there is so much beauty in it. These are the kinds of thoughts mothers (and all women) should be examining, and should be unafraid to discuss with their daughters. But surely, there is room for error here. By telling our daughters that we’re beautiful, they might tend toward believing that physical beauty is more important than it really is. But we all hunger for beauty, even if the topic is taboo. And it’s not taboo...every little girl encounters discussion of beauty, from her first Disney princess movie to her first peek at a magazine in the grocery store aisle. It is better for a mother to claim her own beauty, in a thoughtful and careful way, than for a little girl to encounter it and have no one who is safe to attribute the characteristic to. Instead of believing that they do not possess beauty and it doesn’t matter, girls should believe that they do possess beauty, and it does matter. Just not in the same way our culture constantly tells us. Beauty as it should be is quiet, and is real, and sometimes carries a few extra pounds around the middle. And daughters need to know that. And another thing: most mothers tell their daughters that they--the daughters--are beautiful. And yet what daughter doesn’t believe her mother is blinded by her motherly love? But if a mother claims her own beauty, and explains how beauty is a mixture of body and soul, healthy and full, perhaps the daughter will begin to believe it when her mother insists that she is beautiful. None of us thinks we’re beautiful every day. Even the ones who are beautiful by the magazine covers’ standards have bad days. But if we make a point of telling our daughters about true beauty (both the inside and the outside kind) I think we ourselves will have to question if what we say is true or not. There will always be pretty people. But beauty, more often than not, is something we can choose. ~Ruthie |

Currently Reading

Open and Unafraid David O. Taylor O Pioneers! Willa Cather Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|