|

Last night I sat on my husband's lap and cried into his shoulder. I wasn't really sure why I was crying. In some ways it felt like I was crying over nothing. In other ways it felt like I cried because of everything. I wasn't so upset that I couldn't talk. It was one of those strange moments when tears are coming out of your eyes and snot is welling up in your noes, but you look significantly worse than you feel. All of my thoughts were still with me, and unlike the many other occasions when crying makes them murkier and more confusing, last night's cry put everything into focus.

It's been a weird week. It's been hard to even know why it's been weird. I've been stressed to the max with a Master's thesis I'm trying to write. Each day I've sat down and seriously doubted everything - my topic, my timeline, my brain. Which of course has led me to doubt so many other things about myself - life choices, financial situation, calling. And when I doubt those things, I tend to go on crazy power grabbing hunts. I set my eyes on the best schools I could possibly get into. I make crazy goals for myself like working five career advancing jobs and working out every day and publishing and eating only healthy food and loving everyone I meet and serving in every way possible in my church and getting pregnant right now and cooking more often and... and... and... I recently read an article someone posted on Facebook about how women can't have it all and how we shouldn't be trying to have it all. Last night, what brought me to tears was realizing why I struggle with wanting it all. The question isn't whether I can or should try for it all, but rather, why do I even want it all in the first place? The truth is, more than anything else in life, I want glory. It's like lead poisoning in my soul. It's so much a part of my nature and a part of my environment that I don't even know it's there until I face these weeks when the sheer stress of it all makes the poisoning obvious. I have struggled with this disease my entire life. In fact, I would even go so far as saying that a lust for glory is the single more basic thing for understanding who I am and the decisions I've made. It's been intangible enough that it isn't immediately obvious when looking at my life. But when I think of my youngest self and the way I wanted, truly thirsted after being a princess, movie star, or celebrity more than anything else, I see this desire for glory. Then I grew up a little and my pre-teen interests developed and I fell in love with ice skating and dreams of going to the Olympics, and still it was there. Of course those dreams didn't last, but by then I was a teenager and the definition of glory simply changed. The glory I sought after didn't have to be world-renowned. No, I was pretty content with seeking after the more localized glory of "coolness." I wanted to be cooler than everyone else, alone in my glory among the throngs of the "uncool" world. By college, this desire hadn't quite dissipated, but a different sense of glory was growing in competition. Romance. I wanted to find the one person who would bring me the more adult glory of marriage and sex. That was a long quest, and eventually it choked out the glory of being cool. It's amazing, though, how quickly everything changed once I got married. Almost immediately, my heart made the subtle shift from relational glory to the glory of a career. With one major thing checked off, the glory quest moved on to the next thing. Sometimes I am just so damn tired of it. I have repented and repented and repented again of this thing inside me, but most often it seems like there is just so little to do about it. It is so far, deep, down in my soul that unless I am actively staring it in the face, it will resurrect. It will come back again, and then again in one form or another. It's not the whack-a-mole of sin. At least with whack-a-mole, the mole always looks the same and there are a limited number of spots where it can appear. It's more like the shape-shifting living dead - I can never tell it's there until it's eating me alive because it never looks the same. As I've been struggling through all of this over the past week, a few images have been floating through my head. First, the funerary words, "She hath done what she could," spoken in memory and honor of a dead 19th century missionary wife. (If you want to know where in the world I got that from, ask my thesis.) Second, the image of Furiosa from Mad Max. These are two very incongruous images - there probably isn't anything more oddly juxtaposed than a meek and petticoated woman from two hundred years ago and a feminist icon who rips the bad guys' heads off. But they are deeply linked in my mind. I just watched Mad Max: Fury Road for the first time last weekend. I had wanted to see it when it came out and I read all of the countless reviews raving about Furiosa. But I don't think I could have understood just how striking she is as a character until seeing the movie for myself. She is, hands down, my favorite portrayal of a heroine I have encountered to date. My favorite used to be Tolkien's Eowyn, but Furiosa cast a light on Eowyn I had never noticed before. I haven't read the books and or watched the movies for quite a long time, so my memory may be faulty, but I remember it being pretty clear that Eowyn wants the glory of battle. She is not allowed to go and so there is a lot of discussion about her desire to participate in something so honorable. She wants to protect her home and family, yes, but she honestly also just wants to be part of something so downright great. Eowyn wants glory. Furiosa, on the other hand, is not once portrayed as considering glory, or even herself, in her quest. She has a mission and she will do whatever it takes to complete it. Whereas Eowyn's desire for a glorious quest requires her to be secretive and cut off from the others, Furiosa's mission requires her to know both her strength and her weakness, enabling her to ask for help when and where she needs it. At the end of Eowyn's battle, she has done something remarkable and she has done something good, but there is much about her narrative that is clearly focused on Eowyn and her triumph as a victory for herself. At the end of Furiosa's tale, however, the clear narrative is that "She hath done what she could." I think for my entire life, I have wanted to be Eowyn. I have never been able to look beyond the glory involved in the good things there are to do. I have never been able to truly escape myself in the various quests I've set out upon. But glory is not mine to seek. Glory is something that belongs to God alone. As my sweet husband reminded me last night while my snot and mascara smeared across his sweater, one day, because I am his heir and child, God will glorify me at the end of time as he promised. "For you did not receive the spirit of slavery to fall back into fear, but you have received the Spirit of adoption as sons, by whom we cry, 'Abba! Father!' The Spirit himself bears witness with our spirit that we are children of God, and if children, then heirs - heirs of God and fellow heirs with Christ, provided we suffer with him in order that we may also be glorified with him." But let's be honest, I don't even really know what that means - to be glorified with God one day. So while I may live in the hope of glory, I really can't seek it now, in this life. In the end, I'm not even really sure what I'm trying to process in this post other than that I need Jesus. And I need whatever the anti-lead-poisoning equivalent for the soul is. Which is probably just more of Jesus. I'm really not a fan of the "just open to a certain page and find God's message for you" approach to life, but sometimes it is shocking how well it works. Most nights, I tend to just lie in bed gooning out on my phone while Trey brushes his teeth. But last night, for some inexplicable reason, I put the phone down and picked up Augustine's Confessions. I have it in my stack of books next to my bed as a hopeful "one day I won't look at my phone and will read this instead" reminder. I opened to wherever I had last left off and found the following words. "You have rescued me from all the evil roads I have trodden, and given me a sweetness surpassing all the pleasant by-paths I used to pursue. Let me have a mighty love for you; in my inmost being let me hold tight to your hand, so that you may deliver me from every temptation to the very end." (1.15.24) All of the paths of glory are my lustful temptations, but God has rescued me from them. The cure for my glory-sickened, leaden heart is the same one Augustine sought - to hold tight, very tight, in my inmost being to the hand of God. ~Hannah

1 Comment

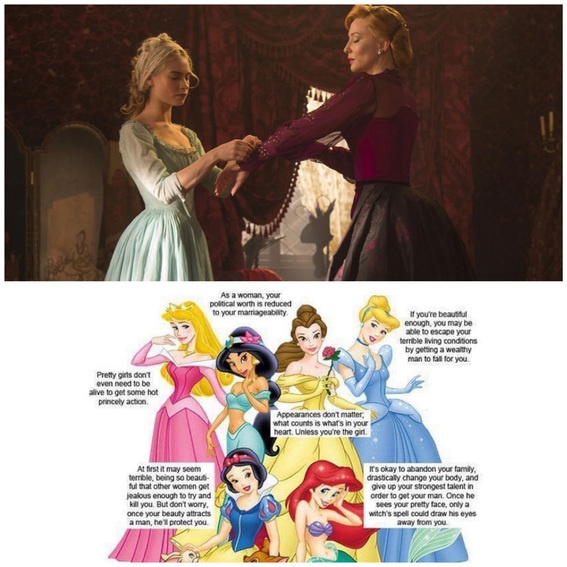

A few years ago there was a popular cartoon floating around Facebook. It depicted the Disney princesses and then purported to unmask the true moral behind each story. Every princesses's story was displayed as derogatory to women in one way or another, and the general idea was how harmful the Disney princesses are for little girls.

While I didn't disagree with every point made in this cartoon (Belle really does seem to have Stockholm syndrome and Ariel really does promote the idea that talking isn't necessary for women to be happy in a relationship), and I do think that much about the Disney princess obsession and culture is unhealthy and at times destructive, much about the cartoon left me befuddled. In particular, I felt confused about the complaints against Cinderella. Cinderella was never my favorite Disney moving growing up and I still don't respond to it emotionally as I do to many of the other films. But my entire opinion of the story changed dramatically in my early 20s. Sometime towards the end or shortly after finishing college, I happened to watch the old cartoon while babysitting some little girls. What I saw amazed me - Cinderella is one of the most woman-centric Disney cartoons made. And I am not unversed in feminist theory - I wrote my senior thesis on the New York Heterodites and Simone de Beauvoir. Let's think about it. There are no men as central characters; all of the primary agents of action are either female or non-human (and even then, the strongest non-human elements are female). My biggest complaint about Cinderella growing up was that it did not depict true love because the prince wasn't a real figure in the story (this is still a valid complaint). But if you are complaining about misogynistic Disney movies, I suggest you reconsider the fact that Cinderella is the only Disney movie thus far in which the prince is pretty much unnecessary. It isn't a true love story, because it's not a story about love. Rather it is a story about one woman's struggle against the circumstances which keep her down. Cinderella repeatedly and methodically works to overcome that which oppresses her through decided and concerted effort with the best means available to her. Isn't this the most simplistic cause of feminism? Since this realization, I've been deeply loyal to the story, and in particular Disney's rendition of it. So, when Kenneth Branagh's version came out last month, it was with both breathless anticipation and dreadsome lothing that I went to see it. In short, this movie could not have better identified and exploited all that is marvelous for women about the Cinderella tale. I've heard many people praise it for its simplicity, lack of cynicism, and willingness to embrace fairytale. These are all indeed commendable. But I don't think it is in these things that its power truly lies. After all, there are times and places for complex stories, cynicism can speak truth, and no story but One should be left unrevised. The real power of Disney's live-action Cinderella is that they got the hidden strength and power of the story right - that not all attributes traditionally associated with women, namely kindness, are signs of weakness. As I think back on Disney's original cartoon and why the Jezebel readership despises it so much, I am convinced it is because Cinderella is too nice. I hear so much about women needing to step up and take control and it often really only amounts to devaluing kindness. As a result, stories that exemplify a woman for displaying such a trait are belittled and mocked. Kindness is associated with an inability to defend or promote oneself, so best to do away with it altogether. But is kindness really about becoming a wet rag? In order to be kind women, must we also be domineered? I find it very sad indeed to associate the two. Sometimes it feels like women are in such a rush and frenzy to do away with the things that have truly oppressed us for so many millennia that we label those true strengths that have always been ours as false and harmful. I propose that kindness is a strength women need to be careful not to weed out of our gardens in order to play with the boys. And Cinderella depicts why this is true. As women, we may be inspired by and fall in love with the Katniss Everdeens of this world. When faced with unimaginable situations, we may hope to take up our arms and fight. At times this may be available to us; there are times when fighting openly and bitterly is in our power. But what about the many times that type of fight is not in our means? What about times when the forces are just too great and we are just too small to become Katniss? What if we are Cinderella? Are we really willing to say that the only strength that matters is the strength to fight? Or do we have a definition of female power that is both big and small enough to include kindness and perseverance in times of trial and duress? Part of the debate around the Disney princesses concerns what values we want to instill in our daughters. As a child and I teenager, I didn't resonate with Cinderella. I resonated with Belle, and Mulan, and Katniss, and Eowyn - the women who were strong and could put up a good fight. I am glad that I had these characters to look up to and be inspired by and I am thankful for parents who never dampened my love of them or tried to instill a singular vision of feminine virtue. I will give my future daughter these women to admire. And I will tell her to fight when and if the time is right. But I will also give my daughter Cinderella. And if my daughter is anything like me, I will give her Cinderella more than the other women, because kindness and perseverance are not my natural gifts. I want my daughter to know that strength is multifaceted. I want her to know that kindness is not weakness. I want her to know that serving the good of others does not mean giving up her agency. Most of all, I want her to know that like Cinderella, there may comes times in which she is not enough to beat the bad guys and when or if that happens, she will need to live in such a way that acknowledges their power but not her moral defeat. As I said above, there is only one Story that does not deserve revision - it is the single story for all ages. The point of this post is not that we should withhold doubt and reexamination from the stories we tell our daughters. What we tell them does shape them more than we can ever imagine. I just don't think our current version of Cinderella is one to do away with, for it rounds out and enlivens all that we want our little girls to grow up to be. ~Hannah  I recently finished reading Wendy Shalit's A Return to Modesty: Discovering the Lost Virtue. It was interesting. A lot of things jumped out immediately. For starters, the book is almost twenty years old and it definitely feels dates at points. She references pop culture quite a lot and everything surrounding date rape, gang rape, hazing, cat-calling, etc. reveals the book's age. Another point of interest is that Shalit is Jewish. Though I don't know where she is religiously now, at the time she wrote the book, she was not Orthodox, sort of. She is definitely enamored with many things stemming from Orthodox Judaism, but she never centers herself within it. As a Christian, this makes her voice really interesting since it's hard to map her ideas over one-to-one with a lot of what is said within conservative Christianity. Lastly, she is overly confident that what she says are obvious to womankind. Her book takes that tone of "all-people-secretly-know-this-and-when-it's-brought-into-the-light-they-will-rejoicingly-forsake-their-ways" that I find so irritating. Most people think they are acting consistently, logically, and morally, so I find any argument unconvincing that assumes people are simply blind. Yet, at the end of the day, I have to give it to Shalit. She wrote a book about modesty that is actually philosophically engaging. How many women exist that can claim that? I disagreed with her on quite a lot, but I would recommend anyone interested in thinking about the topic of modesty to read this book. Unlike just about any conversation I've heard on the topic, Shalit does not stoop to the level of bikinis and yoga pants. Instead, she asks America to engage the topic as one with philosophical depth. Unlike so many of the Evangelical debates that get stuck in the corner of male lust and whether or not women have a role to play in taking responsibility for such lust, Shalit addresses modesty as it actually should be addressed - as a sexual virtue. Her intended audience is not mother's trying to protect teenage boys from themselves or men who don't know how to keep their eyes off their friends' wives; rather, Shalit is writing to the completely secular female college grad who has spent her adult life sleeping around. If my memory serves me right, Shalit doesn't address clothing hardly at all. What she does address is the cultural, ethical, and philosophical milieu in which we live that tells young women they have nothing to protect sexually. The core of Shalit's argument is that modesty is essentially about privacy. Modesty is about maintaining the right to keep to one's self what one chooses. Connected to this is the natural right to make a big deal out of our sexual selves, and our sexual activity. In Shalit's mind, the the loss of modesty in Western society started with the reduction of the gravity of sex. She argues that women naturally treat sex as a big deal and modesty is our natural desire to protect what we believe to be important. Anything that trivializes or reduces the importance of sex, anything that tells women it is "no big deal" is a direct attack on a woman's right to protect her sexual self. Shalit meticulously argues that this is what is under attack in our society today. From classroom sex ed that forces young boys and girls to discuss their development and activity publicly to the common idea that women struggle with "hang ups" sexually if they do not respond in kind to men, Shalit argues that women today have been stripped of their natural tendency to modesty. By telling young teens to be casual and open about their sexual world, particularly by telling young women not to care so much about romantic notions concerning sex, our society is harming women's natural tendencies to protect themselves. Shalit gets a lot wrong, especially in her historical analysis and her romanticization of gender relations in the past, but the Evangelical world would greatly benefit from thinking about modesty along Shalit's lines of thought. In the end, her analysis is right. Modesty is ultimately not about preventing men from committing certain sexual sins. Modesty is about much more fundamental issues. However it is culturally defined, modesty is about the basic right and need of a woman to keep her sexual self as her own, bequeathing the right to share in it only to the beloved of her choosing. Despite all of the talk and hoopla about a woman's body belonging to herself, Shalit demonstrates that the Western world is increasingly and steadily redefining its sexual ethic to establish women's bodies as public entities. In the Evangelical world, all of our arguments about bikinis and yoga pants echo such changes. What we need is not detailed arguments about particular items of clothing, but rather a reexamination of some of the most basic principles. The question is not whether we as women are protecting our brothers, but rather whether we as women are keeping what we want to ourselves? ~ Hannah I first heard someone call God "Mother" in 2005 when I was studying in Washington, DC, during my junior year of college. What shocked me most was not the word itself, but the context. Growing up in university settings, my social circles were pretty diverse and concepts of the divine feminine were not new to me thanks to Hindu playmates and a neighbor who constructed a giant, papermache Mother Earth statue in the back yard for her high school graduation. No, what was shocking that year in DC was that the context was not the already familiar pagan one; rather, the word came from a classmate at an evangelical Christian study program. When it came to her turn to say a prayer before class one afternoon, my classmate started her prayer with "Father, Mother God..." After her address of God is such a manner, I can't remember another single word she said because I was so stunned at what I heard. To whom did she think she was praying?

Well, as usually happens, life kept on going, papers were still due, and I didn't give too much time to either thinking about what had happened or to getting to know this classmate whom I only occasionally saw. I returned from DC to my college outside of Chattanooga and forgot about it even further. But not for long. For my senior thesis in history, I decided to study early 20th century feminist sexual philosophy. It fascinated me and I loved delving into topics about which I had long been curious. Funnily enough, I also found myself in a theology class and the intersection of studying historic Christian doctrine while reading DeBeauvior and the Heterodites left me asking a slew of questions about where and how women fit into God's eternal plan. Why was my faith so male-centric? (This is a topic of vast width and depth, but for some of my initial thoughts on it from a while back, see here). Thankfully I had very wise professors who, rather than dismissing my questions, kindly pointed me in the direction of better questions and I was able to come to a place of peace and faith about having a Heavenly Father. But I still continue to think about and mull over these questions. Ultimately, the question that I have come to is this: Since God has chosen to reveal himself as our Father, what is the significance of this choice? But before coming to this question what I recognized, and what many other women will have to recognize, is simply that God has revealed himself using masculine language rather than feminine. And it is his prerogative. Before any conversation about where and how women fit into God's design and plan, we must first understand God's choice of language for himself. Now I am in seminary and finding plenty more opportunities to think about these questions. They are complex and they are wonderful questions. And they are challenging. Our God is not simple and he is not mild. Even in the midst of serious wrongs against and problems with women in the church, God's character does not alter and he is awesome in his beauty. Anyways, I wrote the following paper for a class and since I found the topic to be really interesting, I thought you all might find it interesting, too. I am not going to tout it as a great piece of research, but hopefully it can be a source of thought as we strive to know and love the God who created male and female and revealed himself as Father. ~Hannah P.S. I took out the footnotes for ease of reading on the blog, but left the bibliography. _______________________________________________________________________________ Naming the Divine: God’s Gender, Feminist Theology, and the Doctrine of Revelation 1. Introduction – Who Are We Talking About? In the last fifty years, feminist theologians have raised a number of fundamental questions about the nature of God. What started as an exploration of and outcry against the church’s history of misogyny led to efforts to see justice done by introducing feminine language for God. The feminist theologians have faced strong criticism from evangelical theologians. At stake within the debate is Christianity’s very understanding of God and his divine right of revelation. More fundamental to the debate are questions about God’s personhood. Whether they are content to maintain the label of Christianity or intent on wrecking the religion as a whole, the feminist theologians examined in this paper all take issue with the traditional orthodox understanding of who God is. This paper will discuss two of the most prominent feminist writers and the disregard for God’s right to reveal himself that underpins their writing. There are many different aspects to feminist arguments for gender inclusive language, but in this paper we will be analyzing the underlying views of God, particularly in the works of Virginia Mollenkott and Mary Daly. Rather than interacting with God according to the language he has chosen, these theologians’ take the right of naming God for themselves, either reducing God to a concept or claiming that the need for female inclusion outweighs God’s communication. The reclamation of the power to name was central to the feminist movement philosophically and these theologians openly talked of the need for renaming God. In response, we will consider how Christian doctrine has held for thousands of years that it is God who reveals himself to us. We do not create him, change him, or name him. As with any person, but especially with the eternal Person, it is not within our power, ability, or rights to alter what God has told us about himself. In response to the feminist theologians, we need to look to one of our most foundational doctrines and carefully consider its application. The starting point of our response must be God’s rightful revelation of himself – that God tells us about himself, names himself, and directs our language towards him. 2. Radical and Evangelical – The Feminist Theologians Feminism’s history with Christianity is long and complex. Feminism and Christianity have not always been oppositional, in contrast to the typical portrayal: many Christian denominations and organizations from the mid 19th century onward provided a home and support structure for various feminist movements. Serious feminist theology, however, did not begin until the late 1960s and started to take significant shape in the 1970s and 1980s. Though a simplified statement, the feminist theologians were initially divided into two groups – radical and evangelical feminists. Both groups believed in the importance and necessity of religion for the further good of women; however, they had very different ideas about what that meant. The evangelical feminists believed the gospel held the power necessary for female transformation and strove to find Biblical support and answers for their causes. The radical feminists were more diverse in their relationship with Christianity. As exemplified in Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow’s popular anthology of radical feminist theology, Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion, the radical feminists either desired to completely transform and alter the core of the Judeo-Christian tradition by looking back to what they claimed to be its roots, which incorporated goddess worship, or they considered themselves “post-Christian” and breaking beyond the boundaries of the Christian faith. Virginia Ramey Mollenkott initially found herself within the evangelical feminist movement and, though perhaps an unlikely candidate, was one of its leading voices. Mollenkott was raised in a strict fundamentalist setting and attended Bob Jones University for her undergraduate degree. She married straight out of school, but went on to complete a Masters and Doctorate in English while raising a family, not a small feat for a woman in the 1950s and 60s. After chairing the English department in a religiously affiliated college, Mollenkott quit her job and found a position at a secular institution in order to clear the way for what she felt to be an inevitable divorce. Shortly thereafter, Mollenkott started to become involved with the Evangelical Women’s Caucus, the center of evangelical feminism, and though Mollenkott’s relationship with evangelicalism eventually completely broke down due to dramatic shifts in her theology and personal life, her first two books on the topic of Biblical feminism had a huge impact. Mary Daly, who held a doctorate in each of the areas of religion, sacred theology, and philosophy, taught at Boston College and sat squarely within the radical feminist camp, if not at its head. One of the first feminist theologians to have a major impact, Daly came from the Catholic tradition, but openly rejected most, if not all, church doctrines. 3. Constructing the Feminine within the Divine A. Virginia Ramey Mollenkott Mollenkott’s arguments are marked as much by what they leave out as by that for which they argue. Apart from certain odd hermeneutical arguments concerning Paul’s writings on women, Mollenkott’s arguments for feminine language for God in Women, Men, & the Bible and The Divine Feminine: The Biblical Imagery of God as Female rely on her understanding of metaphor. The starting point of Mollenkott’s argument for using feminine language for God is that since God is neither male nor female, all language used for him is metaphorical in nature. She writes, “It is vital that we remind ourselves constantly that our speech about God, including the biblical metaphors of God as our Father and all the masculine pronouns concerning God, are figures of speech and are not the full truth about God’s ultimate nature.” From this point, she goes on to assume that because these Biblical metaphors do not capture God’s full nature, they can therefore be changed or altered. Mollenkott further argues that since the cultural context of the Bible should not be absolutized, the presence of feminine imagery for God shows us that the authors intended to encourage their listeners to conceive of God in feminine terms. Mollenkott argues in Men, Women, and the Bible that since the cultural setting of the Bible was strictly patriarchal, any presence of feminine imagery for God would have been a challenge to masculine conceptions of God and a statement on the acceptability of feminine language. She applauds the daring of the Biblical writers for referring to God in the feminine as much as they were able to, since given their cultural context they could not refer to God in feminine language more than they did. This idea forms the basis of her later book, The Divine Feminine, where she looks at a variety of passages with such images as birth pangs (Isaiah 42:14), Lady Wisdom (Proverbs 1-9), and a mother hen (Matthew 23:27) used in connection with God. Mollenkott’s underlying assumption is that it is humanity that names God. She correctly argues that all of the images used for God are inspired; yet she fails to recognize or acknowledge God’s revelation of himself. Mollenkott writes, “The Bible certainly utilizes male imagery concerning God, and Jesus encourages us to call God our Father, so there cannot be anything wrong with that. The problem arises when we ignore, as we have, the feminine imagery concerning God, so that gradually we forget that God-as-Father is a metaphor, a figure or speech, an implied comparison intended to help us relate to God in a personal and intimate way.” Mollenkott is very intentional to say that in interpreting the Bible, we must look for the author’s original intent; however, she does not seem to talk as if God is author behind those humanly involved. In Mollenkott language, primary Biblical authorship lies with the human author and as such, we have the freedom, and even responsibility, to change our language for God based upon current needs. B. Mary Daly In reading Daly’s groundbreaking works, The Church and the Second Sex and Beyond God the Father: Toward a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation, it is hard to escape the influence existentialist philosophy had on her view of God and religion. In The Church and the Second Sex, Daly directly credits Simone de Beauvoir with influencing much, if not all, of her arguments. In The Church and the Second Sex, de Beauvoir’s philosophy is a more direct influence and source for much of Daly’s criticism, but in Beyond God the Father, we see existentialist philosophy more fully thought out and applied to her deconstruction of Christianity. In these two books, we see Daly develop and bring to fullness her arguments for God as Verb and her ideas that transcendence for humanity lies in female liberation. By the end, Daly has taken away any possibility of God’s self-revelation. In The Church and the Second Sex, Daly starts her arguments with pretty traditional feminist criticisms of Christianity, such as skewering its misogynistic history, but she quickly moves on to interlace discussion of de Beauviour’s own criticisms and philosophy of gender. She integrates de Beauvior’s arguments that as an instrument of women’s oppression, the church has kept women in passive roles, prevented them from full participation, and taught them to focus on the after-life as compensation. Daly states, “…the Church by its doctrine implicitly conveys the idea that women are naturally inferior.” Daly then goes on to argue this can be most clearly seen in the doctrines of Mary. Women within the church were forced to abandon the mother-goddess of antiquity and in substitute were given the virgin Mother of God who continually exists in a role subordination. She criticizes what she sees as Greek influence in Christian thought which led to ideas of fixed natures and Jewish influence towards antifeminism. Daly’s most significant issue is with that of fixed natures. Echoing the existentialists, Daly writes in the The Church and the Second Sex that for woman to have her own personhood and freedom, she must be able to develop and define her own nature. Any idea of scripture informing or defining the nature of femininity or womanhood is abhorrent to Daly. She writes, “The characteristics of the Eternal Woman are opposed to those of a developing, authentic person, who will be unique, self-critical, active and searching…” and later “…on all fronts the Eternal Woman is the enemy of the individual woman looking for self-realization and creative expansion of her own unique personhood.” Because the church has argued the nature of gender is immutable and God revealed himself as male, woman cannot enter fully into personhood, so the source of immutable gender must be challenged. To do this, Daly offers a number of solutions. No one really believes God belongs to the male sex, but we continue to speak as such, so “conceptualizations, images, and attributes” of God must be altered. To do so, Christianity must first be de-Hellenized, or moved beyond ideas of omnipotence, immutability, and providence. Second, ideas of biological nature or Natural Law must be ridden as part of the larger need to do away with a static worldview. Third, Christianity must move beyond institutionalism and fourth, beyond ideas of sin. But most importantly for our discussion, Daly calls for the end of the idea of a closed and authoritative revelation. Daly develops her ideas further in her follow up Beyond God the Father. Because of Daly’s views on revelation and scripture, she sees no separation between what the church has been or said and what the Christian view on women is. She says, “The symbol of the Father God, spawned in the human imagination and sustained as a plausible by patriarchy, has in turn rendered service to this type of society by making its mechanisms for the oppression of women appear right and fitting.” God is not above or separate from his people, therefore what the church has said and what the scriptures say are not separated in their implications for women. This is the heart behind Daly’s infamous statement, “…if God is male, then the male is God.” From this point, Daly has very few pretenses of staying within the bounds of Christianity or of relating to the God who reveals himself. Her purpose is to find transcendence and “the search for ultimate meaning and reality, which some would call God.” Key to her argument is the rejection of God as a person to be known. In her view, religion no longer has a relational nature to it and as such there is no God who tells us anything about himself. Without the concept of revelation, the concept of God can be dismantled and rebuilt according to a person or group’s needs. She says, “The various theologies that hypostatize transcendence, that is, those which one way or another objectify ‘God’ as a being, thereby attempt in a self-contradictory way to envisage transcendent reality as finite. ‘God’ then functions to legitimate the existing social, economic, and political status quo, in which women and other victimized groups are subordinate.” And, “I will begin my description with some indications of what my method is not. First of all it obviously is not that of a ‘kerygmatic theology,’ which supposes some unique and changeless revelation peculiar to Christianity or to any religion. Neither is my approach that of a disinterested observer who claims to have an ‘objective knowledge about’ reality. Nor is it an attempt to correlate with the existing cultural situation certain ‘eternal truths’ which are presumed to have been captured as adequately as possible in a fixed and limited set of symbols. None of these approaches can express the revolutionary potential of women’s liberation for challenging the forms in which consciousness incarnates itself and for changing consciousness.” Daly goes on to argue that we should no longer conceive of God as a noun, but rather as a verb, or rather God as Verb. She believes all ideas of God as a person are anthropomorphic, and that hope for women lies in beginning to see God as “Be-ing” in which we can and should participate. She writes, “Women now who are experiencing the shock of nonbeing and the surge of self-affirmation against this are inclined to perceive transcendence as the Verb in which we participate – live, move, and have our being.” Furthermore, the power of naming must be restored to women in addition to participation in the transcendence, or being, of God. This includes the power of naming God. Daly writes, “To exist humanly is to name the self, the world, and God. The ‘method’ of the evolving spiritual consciousness of women is nothing less than this beginning to speak humanly – a reclaiming of the right to name. The liberation of language is rooted in the liberation of ourselves.” Along with God’s being, his name is no longer something revealed, but rather something constructed and reclaimed by womanhood. 4. The Doctrine of Revelation After looking at these arguments, one may ask what an orthodox response should be. Of course, there are many more aspects to these women’s arguments that are not covered in this paper. But I have chosen to look closely at views on revelation because the fundamental question we need to ask is if we are talking about the same God. Who are Daly and Mollenkott talking about? I would propose that unless they are talking about a God who has revealed himself on his own terms, the discussion is about a false god. It is a basic tenant of Christianity that God’s transcendence sets the precedence for our relating to him. In Knowing God, J.I. Packer starts his book with a wonderful observation on the nature of relating to God. He writes, “… the quality of extent of our knowledge of other people depends more on them than on us. Our knowing them is more directly the result of their allowing us to know them than of our attempting to get to know them… Imagine, now, that we are going to be introduced to someone whom we feel to be ‘above’ us… The more conscious we are of our own inferiority, the more we shall feel that our part is simply to attend to this person respectfully and let him take the initiative in the conversation.” If we really believe there is a transcendent God, then we must rely upon what he tells us about himself. We may not understand or like it, or we may see grave misinterpretation by the church of what he has told us, but we are completely dependent on God’s communication of himself to us. In his book on the topic called The Revelation of God, Peter Jensen ties our ability to pray to God to the name by which he reveals himself. Apart from God’s revelation of how we should call upon him, all spiritual relationships are sinister and deceitful. He writes, “Throughout the Bible, our speech directed towards God is understood to be an essential part of this friendship with God. Prayer is virtually a universal human phenomenon, but Christian prayer takes its nature from what we know about God, including the invitations to prayer that he gives us. The prayers of the Bible, including those of Jesus, show that prayer responds to the revelation of God in his word. Its scope, content, and assurance are based on the character of God as he reveals himself. Confident prayer is based on knowing God’s name. As far as Christians are concerned, God is characteristically addressed as Father, in the name of the Son and in the power of the Spirit. This trinitarian intimacy arises from an encounter with the words God has spoken. The Bible does not regard those who are ignorant of God as lacking spiritual relationships, but considers that those relationships are sinister rather than helpful. What Israel in particular has been given is the name of God, by which God’s people may address him with success, in that they may be confident of being heard. Without the name, relationship is impossible. Prayer moves within the ambit of revelation…” In prayer, our most intimate interaction with God, we are told to call God our Father and it is not within our rights or abilities to change this fundamental requirement for relating to God. If it is up to God to reveal himself to us, then we must assume that though the feminist theologians were correct in arguing that God is neither male nor female, they were incorrect in arguing male language for God is optional. In his Christian Theology, Millard J. Erickson says, “Humans cannot reach up to investigate God and would not understand even if they could. So God has revealed himself by a revelation in anthropic form. This should not be thought of as an anthropomorphism as such, but as simply a revelation coming in human language and human categories of thought and action.” If we accept that even God’s anthropic language about himself is revealed, then we do not have the liberty to change the gender of the language used. Erickson also says of God, “The particular names that the personal God assumes refer primarily to his relationship with persons rather than with nature.” We may believe that God is Spirit, and therefore neither masculine nor feminine, but we must believe that his choice to use masculine language and teach us to call him Father was for a relational purpose with his people. 5. Conclusion – Why Should Revelation Matter for Feminism? As the feminist theologians accurately assessed, naming is power. It is not something one does to another unless they have the right to do so and hold a significant degree of authority over the other. The right to name belongs to only a select group of people in this world, parents and the self, and the latter only in renaming. For a disenfranchised group to be empowered, the ability to name is an important right to establish. In Daly’s aggressive linguistic arguments to erase God’s personhood and Mollonkott’s more seemingly benign arguments using various Biblical imagery to refer to God in feminine language, both of these women recognize and lay claim for women to the primal power there is in naming the divine. What the feminist theologians disregard is the fact that it is not their right to rename the transcendent God. By doing so, as Jensen implies, both Daly and Mollenkott break the “friendship with God” that he forges with humanity through his name. God will not be wrestled into a new identity because of the very real injustice done to women; rather, he first demands relationship according to his will, and then promises freedom and restoration. The issues addressed by the feminist theologians are real ones and as such, Christians should participate in the conversations surrounding feminism; however, we must remember in doing so that God is not a concept to be changed for the benefit of humanity. God is the transcendent, triune Person about whom we can know nothing unless he reveals himself. In this, we should find hope because this Person who tells us about himself is all-powerful and just. The God who Is tells us about himself and he tells us that he will put to right all that has been wrong. Bibliography: Christ, Carol P., and Judith Plaskow, ed. Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1979. Cochran, Pamela D.H. Evangelical Feminism: A History. New York: New York University Press, 2005. Daly, Mary. Beyond God the Father: Toward a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation. Boston: Beacon Press, 1973. Daly, Mary. The Church and the Second Sex. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1968. Erickson, Millard J. “God’s Particular Revelation.” In Christian Theology, 200-223. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 1983. Erickson, Millard J. “The Greatness of God.” In Christian Theology, 289-308. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 1983. Jensen, Peter. The Revelation of God. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 2002. Mollenkott, Virginia Ramey. The Divine Feminine: The Biblical Imagery of God as Female. New York: Crossroad, 1983. Mollenkott, Virginia Ramey. Women, Men, and the Bible. Nashville: Abingdon, 1977. Mossman, Jennifer, ed. Reference Library of American Women, Volume I. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Research, 1999. Packer, J.I. Knowing God. Downer’s Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1973.  In her 2005 book, Female Chauvinist Pigs: Women and the Rise of Raunch Culture, Ariel Levy addresses what anyone with two eyes has noticed – American culture celebrates a raunchy version of female sexuality with gusto and flair. This isn’t new information to anyone. But what Levy does highlight in a new way is the more than willing participation (and even leadership) of American women in creating and developing an environment where prostitutes, strippers, and three-somes are considered the ideals of thrillingly liberated womanhood. But again, this is nothing new to anyone who turns on the television or picks up a magazine once in a while. Phenomena such as Girls Gone Wild, Paris Hilton, reality tv, and pole dancing have become so integrated with pop culture that one no longer needs to read an entire book (nonetheless a review!) about the trend to notice it. So what is this review about? What kept me reading Levy’s book and caused me to furiously underline almost every paragraph was her own response as an avowed feminist to the problem. The reader senses Levy’s natural outrage at what she investigates, particularly in her chapter concerning the effects raunch culture (female exhibitionism) has on teenage sexuality, but she cannot bring herself to give moral weight or significance to the cultural trend. Levy’s worldview does not provide her with a strong enough reason to reject what bothers her so intensely. She feels something is wrong, but has only shallow arguments with which to try and persuade a self-indulgent culture that porn stars really are not the ideal images of female liberation. Levy’s one and only argument against raunch culture is interestingly post-modern. The stereotypical post-modern argument for female liberation starts with the individual creating her own truth and happiness. Because Levy agrees, she carefully repeats throughout her book that raunch culture does not bother her in and of itself. According to Levy, what bothers her, and deeply so, is the way in which she feels all women are pressured into such trends, often by other women. In other words, Levy wants to say some women do naturally desire to be porn stars and flaunt certain kinds of sexuality, but she personally does not want to, so it should not be a cultural standard for women. Levy views sex as a mysterious thing that every person should experiment with in order to discover her personal preferences. Therefore, society should have no culturally prescribed expressions of it. The only criticism Levy makes of raunch culture is that all women are expected to participate in it as a collective standard for female sexual liberation. Female Chauvinist Pigs displays Levy’s passion concerning female sexual trends, but it is exactly that passion which weakens Levy’s actual argument against raunch culture. Almost every page of her book belies an outrage and disgust at something Levy cannot seem to fully accept even despite her stated qualifications. The book’s central argument at times seems completely lost as Levy first works to document trends and occurrences she finds outrageous and then quickly inserts her relativist objections. She repeatedly shows the unhappiness, dishonesty, and lack of sexual pleasure the women she interviews experience, and yet she is constantly stating that she is sure some woman somewhere actually enjoys such sexual exhibitionism. Additionally, she dedicates a significant portion of her text to arguing that most people, male and female, do not like the current trend. In a book where the philosophical stance is that there should be no overarching standards or sexual ideals, her arguments against the trend because “most” people do not like it does not fit. Levy waffles between her passionate dislike of raunch culture and a highly intellectual and relativistic criticism of it. But even Levy’s philosophical objections to the current trend do not deal with the real problem: the communal nature of humanity. Her argument is based solely on the individual. What the individual wants and likes, she should get. There is no consideration made for the fact that very few women, let alone people, make decisions based solely on what they want or like without any influence from peers. There is no realm of life where this is more true for a woman than in the realm of sex. Female sexuality is grounded on being delighted in and admired by the partner. When the number of sexual partners is limitless, though, so are the number sexual competitors. Life does not give women a relational vacuum in which to decide what they want and like in order to then just go out and get it. The things we learn about ourselves and the things that define us exist against the backdrop of every person, male and female, we are connected to and engage with throughout our lives. And as our world gets smaller and smaller, the number of people we interact with increases. For a woman desiring to be sexually admired and valued in a world where there are no expectations for the responsibility of doing so belonging to one person, the push towards exhibitionism is only natural. The larger the pool for competition, the more a woman must do and display to single herself out as desirable. Oddly enough, Levy adds an afterword in which she argues that the thing to combat the tide of raunch culture is a new generation of idealists. I assume she means to promote the ideal of each woman’s prerogative to define sex for herself. As I just argued, though, it does not work. Levy is right that what we need is a new idealism. But instead, I propose the old fashioned ideal of one woman and one man, for life. Women do want to be admired and delighted in sexually, but if we make sex a limitlessly individualistic endeavor, we also make it a limitlessly competitive endeavor. People do vicious things when in boundary-less competition with one another; on the other hand, rules provide safety and promote consideration within a community. I even venture to say that rules are what create community. The difference between a society of individuals competing endlessly for attention and a community living in harmonious respect for each other is often the rules and agreements by which the community lives. Concerning female expression of sexuality, the only thing that will halt the current trend will be a rise of communities committed to following shared rules for the benefit each individual. ~Hannah During my vacation, I was unexpectedly stuck in Phnom Penh while waiting for my stolen passport to be replaced. Upon arriving in the city, my roommate and I didn't have a hotel booked and ended up heading to the closest hostel that seemed decent. Everything about it seemed fine - location was great, rooms were big and clean, owners were helpful - until I woke up in the middle of the night to hear English speaking men making a ruckus with Cambodian women. They were audibly very drunk and in the process of the completing the night by getting the women into their hostel rooms. The next morning, I sat outside my room in order to get a better wireless connection and witnessed one of saddest scenes. The two men where young Americans and they were in the process of paying and sending off the Cambodian prostitutes they had brought back in the night. The women's eyes were bloodshot and though they laughed and smiled at the men as they said goodbye, the look of emptiness was unmistakable. One girl sat across from me while waiting for her friend and my heart broke for her. I don't know how exactly to describe her expression, but in addition to emptiness, it contained sadness, weariness, and hardness. It was not the face of a woman who liked herself. I felt repulsed by her, but hut for her; however, the real repulsion came when I looked at the men. Deep, deep anger, loathing, and hatred was inside of me. I felt nauseous. A very long string of curses came to mind, but I won't write them down. What misery for all involved. What evil really does exist. A woman can legally work as a prostitute in Cambodia when she is 18 years old, but many are forced, or sold, into the work. I don't know what these two women's stories were, but bumping into them gave a whole new meaning to the anti-trafficking signs posted all over the country. Many hotels in Phnom Penh specifically state if they are "No Sex Tourism Allowed" locations and I quickly learned to look for such places when booking places to stay the city. Please take time to watch the following videos. The third one isn't possible to embed, but please take the time to click on the url. This is the largest form of slavery in our modern world. This evil does exist beyond your computer screen. I've seen it now first hand. ~Hannah |

Archives

October 2018

Categories

All

|