In celebration of resurrecting my personal blog, I'm posting a question that was asked of me a few days ago. "Would you rather live in a world where the phoenix or dragons exist?" I unequivocally answered the phoenix. To start with complete honesty, I have a mild obsession with all things bird, so it was my natural inclination. But a big beautiful bird that has healing powers and represents new life coming out struggle? Yes please! Could anything be better in the mythological world? Since then, though, I've thought more about dragons. When the question was asked, I was thinking of them as representations of the terrible. Fearful and damage wreaking, they weren't really something I would ever want to exist. But they really are so much more. Dragons represent a sense of quest. They and their defeat are the end goal towards which so much of the mythological world hurtles. Dragons are the something bigger than self which must be overcome, the thing which gets a man up on his feet to seek good and glory for all. While I might not want a world in which dragons exist, I certainly do want a world in which people live to do something about the dragons. And who can deny that dragons do really lurk in towering caves over our world? So, while I still stand by my answer concerning the phoenix, wanting a world in which life and healing are able to be found, I also forsake my dismissal of dragons. I just might alter the question a bit, for really in the end, what I desire are people who live out and under a sense of sacrificial, and thereby beautiful, quest. What's your vote? ~Hannah

0 Comments

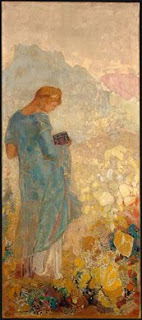

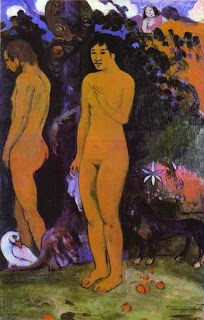

Recently, I’ve developed an interest in mythology as the imaginative representations of cultural beliefs and ideals. Beautiful pictures and stories from across the globe fascinate me, but currently, none more than the myth of the Fenghuang, or Chinese “phoenix”. Due to millennia of Fenghuang mythology, the creature’s symbolism is sometimes conflicted. But here is what I’ve gathered and why I think it matters for contemporary American women… The Fenghuang is part of ancient Chinese cosmology and was responsible along with three other mythological creatures for the creation of the world. After these creatures had created our world, they divided it into four sectors of north, south, east, and west, each taking dominion over one. The Fenghuang’s domain was the south and as a result, the summer. This mythological creature’s body symbolizes the six celestial bodies with its head as the sky, eyes as the sun, back as the moon, wings as the wind, feet as the earth, and finally, tail as the planets. The actual physical appearance of the Fenghuang is a composite of many different animals. The creature is made up of the beak of a cock, the face of a swallow, the forehead of a fowl, the neck of a snake, the breast of a goose, the back of tortoise, the hindquarters of a stag, and the tail of a fish. This sounds like quite the odd looking creature to me, but interestingly enough, artistic depictions of the Fenghuang never seem to show the bird’s described physical make-up. Instead it is depicted as a beautiful and graceful composite of many bird varieties, most often with a peacock tail with feathers made of the five fundamental colors black, red, green, white, and yellow (corresponding to the five elements of water, fire, wood, metal, and earth). In China’s most ancient mythology, the Fenghuang was actually two birds united together. Feng represented the male entity and huang the female. United together to create the Fenghuang, they were a metaphor of the yin and yang, as well as the sacred union of male and female. Used to symbolize peace and harmony, the Fenghuang was said to appear only at the beginning of a new era or at the ascension to the thrown of a benevolent ruler. More recently in China’s long history, though, the Feng and Huang have been merged into one female creature, the Fenghuang, so that the ancient mythological figured could be paired with the male dragon as a symbol for the empress and emperor. In more recent centuries, the dragon and phoenix are often seen paired together as a symbol for marriage and unity. What draws me to the Fenghuang is a particular ancient description of its symbolism. In the Shan Hai Jing (山海经), a classic of Chinese mythology, each part of the Fenghuang’s body symbolizes a word. The head represents virtue (德), the wings represent duty (義), the back represents propriety (禮), the abdomen represents belief (信), and the chest represents mercy (仁). What a beautiful symbol for femininity! When I think about contemporary American culture, it’s hard for me to come up with any myths as deep symbols for femininity. We have larger than life caricatures of women as sex toys, power-hungry achievers, or spineless and wimpy prey, but there is a fundamental difference between myth and caricature. Caricature is based on what people perceive to exist. Myth presents what people want to be. The beauty of mythology is that it takes us beyond reality and gives us a chance to create an ideal. What does it say about us women if we do not have any collective symbols beyond our reality to remind us of what we hope to become? If I could pick a mythological symbol to inspire modern women, I would pick the Fenghuang. The creature flies with beauty and strength, ushering in times of peace and harmony. It is virtuous as it carries out its duty. Representing a life filled with belief (I would add, belief in something bigger than itself), the Fenghuang is marked by mercy and compassion. Lastly, the Fenghuang symbolizes propriety, a lost word in contemporary times. But the word has richer meaning than its surfaces usage. In addition to referring to manners of behavior, propriety means “appropriateness to the purpose or circumstances” and “rightness or justness.” Who could argue that justness and an understanding of one’s circumstances are a beautiful component of feminine ideals? I wish our society would dream again and intrigue us with its ideals. ~Hannah  For two and a half years now, I've been discussing Christianity with Chinese friends. In these discussions, my understanding of my own worldview has grown in unexpected ways due to difficult or complicated questions posed to me by my friends. Usually a topic is brought up, they express their reservations about it, and I am forced to admit I don't have a ready answer. One such confusing topic is Eve's involvement in the fall of mankind. What surprises me when discussing this topic with my Chinese friends is that they think Eve was condemned for curiosity. Growing up in a Christian home, I was always told Eve was condemned for rebellion against God, not human curiosity. Additionally, my Chinese friends quickly jump to the conclusion that Eve receives the entire blame for evil entering the world, another contradiction to what I was taught. It bothers them to see the female sex blamed for the world’s evil and problems. After all, isn’t curiosity a natural part of human existence? A few weeks ago, I read something that shed light on this topic for me and has caused me to contemplate the Western worldview’s conflicting influences. I climbed into bed and took out Bulfinch's The Age of Fable for light reading before sleep. Remembering a painting depicting the story of Pandora I once saw and loved, I decided to educate myself and actually read the myth. In one short paragraph, my mind was filled with thoughts that kept me awake for some time. The Greek myth of Pandora relates how evil was brought into the world by the accident of a woman. In some ways, it resembles the Biblical account of Eve's participation in bringing evil into the world, and yet there are crucial differences. Within the West’s literary and religious heritage, we find competing descriptions of womanhood. Bulfinch's recount of the myth reads as such: "Woman was not yet made. The story (absurd enough!) is that Jupiter made her, and sent her to Prometheus and his brother, to punish them for their presumption in stealing fire from heaven; and man, for accepting his gift. The first woman was named Pandora. She was made in heaven, every god contributing something to perfect her. Venus gave her beauty, Mercury persuasion, Apollo music, etc. Thus equipped, she was conveyed to earth, and presented to Epimetheus, who gladly accepted her, though cautioned by his brother to beware of Jupiter and his gifts. Epimetheus had in his house a jar, in which were kept certain noxious articles for which, in fitting man for his new abode, he had had no occasion. Pandora was seized with an eager curiosity to know what this jar contained; and one day she slipped off the cover and looked in. Forthwith there escaped a multitude of plagues for hapless man, -such as gout, rheumatism, and colic for his body, and envy, spite and revenge for his mind, -and scattered themselves far and wide. Pandora hastened to replace the lid! but, alas! the whole contents of the jar had escaped, one thing only excepted, which lay at the bottom, and that was hope. So we see at this day, whatever evils are abroad, hope never entirely leaves us; and while we have that, no amount of other ills can make us completely wretched." In Pandora's tale, the creation of woman is a punishment, which is alone cause for concern, but even more interesting is the relationship between woman and evil. Evil is a problem that comes from outside of Pandora, rather than something that lies within, thus making the release of evil into our world an excusable mistake. The justifiable act of curiosity gets the better of woman by accident. Though woman herself is a punishment for an act of treachery, the action that brings evil upon humanity is not condemnable. Evil's entrance to the world is grieved and regretted, but not condemned because the culprit made a mistake rather than a choice. Pandora is a victim who is not held accountable, thus stripping her of a protagonist’s role. In short, woman is a curse without moral accountability for her decisions. In the Biblical narrative, we see almost the exact opposite. Genesis 2-3 reads: "And the LORD God said, 'It is not good that man should be alone; I will make him a helper comparable to him.' Out of the ground the LORD God formed every beast of the field and every bird of the air, and brought them to Adam to see what he would call them. And whatever Adam called each living creature, that was its name. So Adam gave names to all cattle, to the birds of the air, and to every beast of the field. But for Adam there was not found a helper comparable to him. And the LORD God caused a deep sleep to fall on Adam, and he slept; and He took one of his ribs, and closed up the flesh in its place. Then the rib which the LORD God had taken from man He made into a woman, and He brought her to the man. And Adam said: 'This is now bone of my bones And flesh of my flesh; She shall be called Woman, Because she was taken out of Man.' Therefore a man shall leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and they shall become one flesh. And they were both naked, the man and his wife, and were not ashamed. Now the serpent was more cunning than any beast of the field which the LORD God had made. And he said to the woman, 'Has God indeed said, ‘You shall not eat of every tree of the garden?'' And the woman said to the serpent, 'We may eat the fruit of the trees of the garden; but of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of the garden, God has said, ‘You shall not eat it, nor shall you touch it, lest you die.’' Then the serpent said to the woman, 'You will not surely die. For God knows that in the day you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.' So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, that it was pleasant to the eyes, and a tree desirable to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate. She also gave to her husband with her, and he ate. Then the eyes of both of them were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made themselves coverings. And they heard the sound of the LORD God walking in the garden in the cool of the day, and Adam and his wife hid themselves from the presence of the LORD God among the trees of the garden." Here, Eve is a protagonist, someone capable of making important decisions. In the beginning, Eve is in her being and essence a blessing to mankind. Her purpose and existence is to fill a void, the answer to a felt need recognized by God. With her arrival, human relationship begins and she is recognized for her physical, mental, and moral comparability to Adam. Most importantly, she is a responsible being who will be held accountable for her actions. In Genesis, curiosity in not the cause for evil's entrance to the world. Evil enters by willful action, a choice to disregard the truth and forget the promises of God. There is no victimization by others, rather a sad and despicable rebellion. This distinction is incredibly important to the way we view ourselves as women. One of the most common misunderstandings of Biblical Christianity that I've come across in my relationships with Chinese women is that Eve ate the fruit and fell from grace because she was curious. And how could God punish someone for being curious? For my friends, it’s like asking, how could God punish woman for being human? We women need to reexamine what our inherited Western worldview tells us about Eve, learning to distinguish between the dignity given to woman in the Biblical account and the assumed Pandoraish version of the story we’ve inherited and is passed on to those outside the West. If we think of Eve as a Pandorian mistake-maker, then God’s condemnation of mankind truly does smack of injustice. But if I look at the Biblical account without the centuries long influence of Greek mythology, I find a much more dignifying, though terrifying, explanation for the state of woman’s sorrow and of the world. The picture of womanhood given us by Pandora is the globally common and pagan one, and it is this version that has helped create the marginalization of women. A summation of this view goes, "Women don't know what they are doing, they can't be trusted, so to keep them from making harmful mistakes, keep them out of the loop." To say our involvement in the destruction of mankind was a mistake is the first step to giving up our dignity, our rationality, and our voice. Interestingly, this is the first thing the Biblical account describes Eve doing after her eyes are opened to evil. Eve’s first statements after eating the fruit pass the blame of her actions on to someone else. She removes herself from the protagonist’s position and assumes the role of victim. Man was not the first to victimize woman, keeping her from being an active participant in the world’s decisions. Woman was the first to do so. Our mother Eve victimized herself and the rest of us when she told the first myth that it was someone else’s vault she ate the fruit. Since then, every victimizing myth, every story or fable that has made women helpless and stupid is only a retelling of what Eve herself declared to God when asked who was responsible. Pandora was Eve’s creation. So how do we respond? By no means am I writing that women should be proud of Eve's actions. But I do believe that if women want to claim "comparableness" to Adam, our first step should be to stop passing the blame were it isn’t justified. Our second step should be to stop blaming the Bible for the victimization of women, for in its texts, even in woman’s worst moment, she is given more dignity than the world’s myths provide. And lastly, through my conversations with Chinese friends, I’ve learned that the third step is to grieve the reality in which we live and to reach out for the overwhelming grace given woman by her Creator. ~Hannah |

Archives

October 2018

Categories

All

|