|

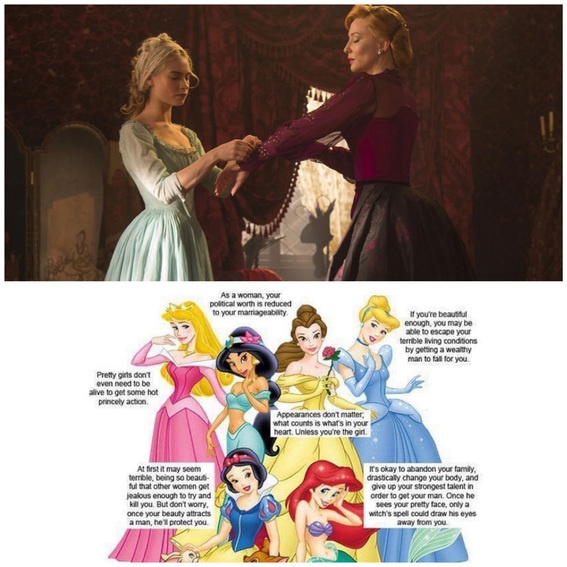

A few years ago there was a popular cartoon floating around Facebook. It depicted the Disney princesses and then purported to unmask the true moral behind each story. Every princesses's story was displayed as derogatory to women in one way or another, and the general idea was how harmful the Disney princesses are for little girls.

While I didn't disagree with every point made in this cartoon (Belle really does seem to have Stockholm syndrome and Ariel really does promote the idea that talking isn't necessary for women to be happy in a relationship), and I do think that much about the Disney princess obsession and culture is unhealthy and at times destructive, much about the cartoon left me befuddled. In particular, I felt confused about the complaints against Cinderella. Cinderella was never my favorite Disney moving growing up and I still don't respond to it emotionally as I do to many of the other films. But my entire opinion of the story changed dramatically in my early 20s. Sometime towards the end or shortly after finishing college, I happened to watch the old cartoon while babysitting some little girls. What I saw amazed me - Cinderella is one of the most woman-centric Disney cartoons made. And I am not unversed in feminist theory - I wrote my senior thesis on the New York Heterodites and Simone de Beauvoir. Let's think about it. There are no men as central characters; all of the primary agents of action are either female or non-human (and even then, the strongest non-human elements are female). My biggest complaint about Cinderella growing up was that it did not depict true love because the prince wasn't a real figure in the story (this is still a valid complaint). But if you are complaining about misogynistic Disney movies, I suggest you reconsider the fact that Cinderella is the only Disney movie thus far in which the prince is pretty much unnecessary. It isn't a true love story, because it's not a story about love. Rather it is a story about one woman's struggle against the circumstances which keep her down. Cinderella repeatedly and methodically works to overcome that which oppresses her through decided and concerted effort with the best means available to her. Isn't this the most simplistic cause of feminism? Since this realization, I've been deeply loyal to the story, and in particular Disney's rendition of it. So, when Kenneth Branagh's version came out last month, it was with both breathless anticipation and dreadsome lothing that I went to see it. In short, this movie could not have better identified and exploited all that is marvelous for women about the Cinderella tale. I've heard many people praise it for its simplicity, lack of cynicism, and willingness to embrace fairytale. These are all indeed commendable. But I don't think it is in these things that its power truly lies. After all, there are times and places for complex stories, cynicism can speak truth, and no story but One should be left unrevised. The real power of Disney's live-action Cinderella is that they got the hidden strength and power of the story right - that not all attributes traditionally associated with women, namely kindness, are signs of weakness. As I think back on Disney's original cartoon and why the Jezebel readership despises it so much, I am convinced it is because Cinderella is too nice. I hear so much about women needing to step up and take control and it often really only amounts to devaluing kindness. As a result, stories that exemplify a woman for displaying such a trait are belittled and mocked. Kindness is associated with an inability to defend or promote oneself, so best to do away with it altogether. But is kindness really about becoming a wet rag? In order to be kind women, must we also be domineered? I find it very sad indeed to associate the two. Sometimes it feels like women are in such a rush and frenzy to do away with the things that have truly oppressed us for so many millennia that we label those true strengths that have always been ours as false and harmful. I propose that kindness is a strength women need to be careful not to weed out of our gardens in order to play with the boys. And Cinderella depicts why this is true. As women, we may be inspired by and fall in love with the Katniss Everdeens of this world. When faced with unimaginable situations, we may hope to take up our arms and fight. At times this may be available to us; there are times when fighting openly and bitterly is in our power. But what about the many times that type of fight is not in our means? What about times when the forces are just too great and we are just too small to become Katniss? What if we are Cinderella? Are we really willing to say that the only strength that matters is the strength to fight? Or do we have a definition of female power that is both big and small enough to include kindness and perseverance in times of trial and duress? Part of the debate around the Disney princesses concerns what values we want to instill in our daughters. As a child and I teenager, I didn't resonate with Cinderella. I resonated with Belle, and Mulan, and Katniss, and Eowyn - the women who were strong and could put up a good fight. I am glad that I had these characters to look up to and be inspired by and I am thankful for parents who never dampened my love of them or tried to instill a singular vision of feminine virtue. I will give my future daughter these women to admire. And I will tell her to fight when and if the time is right. But I will also give my daughter Cinderella. And if my daughter is anything like me, I will give her Cinderella more than the other women, because kindness and perseverance are not my natural gifts. I want my daughter to know that strength is multifaceted. I want her to know that kindness is not weakness. I want her to know that serving the good of others does not mean giving up her agency. Most of all, I want her to know that like Cinderella, there may comes times in which she is not enough to beat the bad guys and when or if that happens, she will need to live in such a way that acknowledges their power but not her moral defeat. As I said above, there is only one Story that does not deserve revision - it is the single story for all ages. The point of this post is not that we should withhold doubt and reexamination from the stories we tell our daughters. What we tell them does shape them more than we can ever imagine. I just don't think our current version of Cinderella is one to do away with, for it rounds out and enlivens all that we want our little girls to grow up to be. ~Hannah

1 Comment

I've read a couple of great posts recently and thought I would share. It's always exciting to find people either saying the things you want to say or saying things your mind simply isn't smart enough to think of. So here are some borrowed words on topics we love to discuss at Carved to Adorn. First, Ruthie found an amazing article over at First Things on Lena Dunham's Girls, Jane Austen's Mansfield Park, and the sacred stories we tell. Alan Jacobs's thoughts are chewy, but every bite is fantastic. "What we need is not condemnation of Adam, or condemnation of Hannah for liking Adam, but better art and better stories, better fictional worlds, by which I mean fictional worlds that rhyme with what is the case, with what is true yesterday, today, and forever. Not the abolition of mythic sandboxes but the making of sandboxes in which to play with true, or truer, myths: fictive spaces in which Hannah can do better than Adam, and Adam can be better than what he is, a bitter prisoner of past angers and resentments." Read it here. Second, in order to help keep the conversation about female sexuality going, I recommend Jordan Monge's post yesterday on Her.meneutics titled The Real Problem with Female Masturbation, Call It What It Is: Ladies Who Lust. I'm not sure that I agree with everything in it, but it is an honest discussion and a good place to start. Please add any thoughts you have about it to our comments! Lastly, since I'm sure we could all use a good laugh after reading the first two articles, I give you this to end on a lighter note. If you're like me and secretly wish you lived in an Anthropologie storefront, you will identify with these 87 thoughts. ~ Hannah  Recently, I’ve developed an interest in mythology as the imaginative representations of cultural beliefs and ideals. Beautiful pictures and stories from across the globe fascinate me, but currently, none more than the myth of the Fenghuang, or Chinese “phoenix”. Due to millennia of Fenghuang mythology, the creature’s symbolism is sometimes conflicted. But here is what I’ve gathered and why I think it matters for contemporary American women… The Fenghuang is part of ancient Chinese cosmology and was responsible along with three other mythological creatures for the creation of the world. After these creatures had created our world, they divided it into four sectors of north, south, east, and west, each taking dominion over one. The Fenghuang’s domain was the south and as a result, the summer. This mythological creature’s body symbolizes the six celestial bodies with its head as the sky, eyes as the sun, back as the moon, wings as the wind, feet as the earth, and finally, tail as the planets. The actual physical appearance of the Fenghuang is a composite of many different animals. The creature is made up of the beak of a cock, the face of a swallow, the forehead of a fowl, the neck of a snake, the breast of a goose, the back of tortoise, the hindquarters of a stag, and the tail of a fish. This sounds like quite the odd looking creature to me, but interestingly enough, artistic depictions of the Fenghuang never seem to show the bird’s described physical make-up. Instead it is depicted as a beautiful and graceful composite of many bird varieties, most often with a peacock tail with feathers made of the five fundamental colors black, red, green, white, and yellow (corresponding to the five elements of water, fire, wood, metal, and earth). In China’s most ancient mythology, the Fenghuang was actually two birds united together. Feng represented the male entity and huang the female. United together to create the Fenghuang, they were a metaphor of the yin and yang, as well as the sacred union of male and female. Used to symbolize peace and harmony, the Fenghuang was said to appear only at the beginning of a new era or at the ascension to the thrown of a benevolent ruler. More recently in China’s long history, though, the Feng and Huang have been merged into one female creature, the Fenghuang, so that the ancient mythological figured could be paired with the male dragon as a symbol for the empress and emperor. In more recent centuries, the dragon and phoenix are often seen paired together as a symbol for marriage and unity. What draws me to the Fenghuang is a particular ancient description of its symbolism. In the Shan Hai Jing (山海经), a classic of Chinese mythology, each part of the Fenghuang’s body symbolizes a word. The head represents virtue (德), the wings represent duty (義), the back represents propriety (禮), the abdomen represents belief (信), and the chest represents mercy (仁). What a beautiful symbol for femininity! When I think about contemporary American culture, it’s hard for me to come up with any myths as deep symbols for femininity. We have larger than life caricatures of women as sex toys, power-hungry achievers, or spineless and wimpy prey, but there is a fundamental difference between myth and caricature. Caricature is based on what people perceive to exist. Myth presents what people want to be. The beauty of mythology is that it takes us beyond reality and gives us a chance to create an ideal. What does it say about us women if we do not have any collective symbols beyond our reality to remind us of what we hope to become? If I could pick a mythological symbol to inspire modern women, I would pick the Fenghuang. The creature flies with beauty and strength, ushering in times of peace and harmony. It is virtuous as it carries out its duty. Representing a life filled with belief (I would add, belief in something bigger than itself), the Fenghuang is marked by mercy and compassion. Lastly, the Fenghuang symbolizes propriety, a lost word in contemporary times. But the word has richer meaning than its surfaces usage. In addition to referring to manners of behavior, propriety means “appropriateness to the purpose or circumstances” and “rightness or justness.” Who could argue that justness and an understanding of one’s circumstances are a beautiful component of feminine ideals? I wish our society would dream again and intrigue us with its ideals. ~Hannah |

Archives

October 2018

Categories

All

|