|

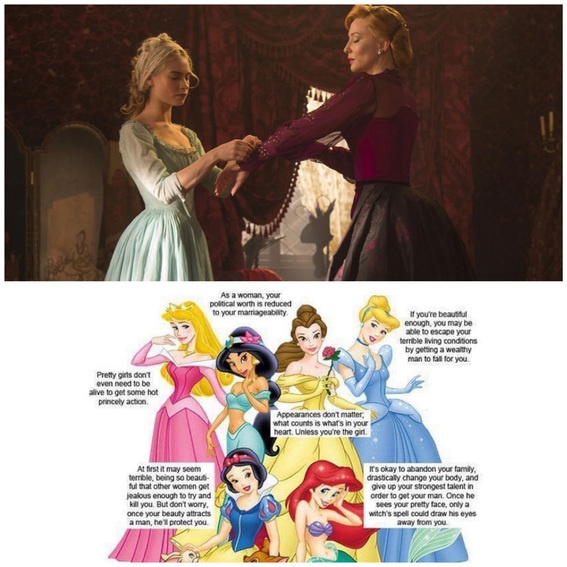

A few years ago there was a popular cartoon floating around Facebook. It depicted the Disney princesses and then purported to unmask the true moral behind each story. Every princesses's story was displayed as derogatory to women in one way or another, and the general idea was how harmful the Disney princesses are for little girls.

While I didn't disagree with every point made in this cartoon (Belle really does seem to have Stockholm syndrome and Ariel really does promote the idea that talking isn't necessary for women to be happy in a relationship), and I do think that much about the Disney princess obsession and culture is unhealthy and at times destructive, much about the cartoon left me befuddled. In particular, I felt confused about the complaints against Cinderella. Cinderella was never my favorite Disney moving growing up and I still don't respond to it emotionally as I do to many of the other films. But my entire opinion of the story changed dramatically in my early 20s. Sometime towards the end or shortly after finishing college, I happened to watch the old cartoon while babysitting some little girls. What I saw amazed me - Cinderella is one of the most woman-centric Disney cartoons made. And I am not unversed in feminist theory - I wrote my senior thesis on the New York Heterodites and Simone de Beauvoir. Let's think about it. There are no men as central characters; all of the primary agents of action are either female or non-human (and even then, the strongest non-human elements are female). My biggest complaint about Cinderella growing up was that it did not depict true love because the prince wasn't a real figure in the story (this is still a valid complaint). But if you are complaining about misogynistic Disney movies, I suggest you reconsider the fact that Cinderella is the only Disney movie thus far in which the prince is pretty much unnecessary. It isn't a true love story, because it's not a story about love. Rather it is a story about one woman's struggle against the circumstances which keep her down. Cinderella repeatedly and methodically works to overcome that which oppresses her through decided and concerted effort with the best means available to her. Isn't this the most simplistic cause of feminism? Since this realization, I've been deeply loyal to the story, and in particular Disney's rendition of it. So, when Kenneth Branagh's version came out last month, it was with both breathless anticipation and dreadsome lothing that I went to see it. In short, this movie could not have better identified and exploited all that is marvelous for women about the Cinderella tale. I've heard many people praise it for its simplicity, lack of cynicism, and willingness to embrace fairytale. These are all indeed commendable. But I don't think it is in these things that its power truly lies. After all, there are times and places for complex stories, cynicism can speak truth, and no story but One should be left unrevised. The real power of Disney's live-action Cinderella is that they got the hidden strength and power of the story right - that not all attributes traditionally associated with women, namely kindness, are signs of weakness. As I think back on Disney's original cartoon and why the Jezebel readership despises it so much, I am convinced it is because Cinderella is too nice. I hear so much about women needing to step up and take control and it often really only amounts to devaluing kindness. As a result, stories that exemplify a woman for displaying such a trait are belittled and mocked. Kindness is associated with an inability to defend or promote oneself, so best to do away with it altogether. But is kindness really about becoming a wet rag? In order to be kind women, must we also be domineered? I find it very sad indeed to associate the two. Sometimes it feels like women are in such a rush and frenzy to do away with the things that have truly oppressed us for so many millennia that we label those true strengths that have always been ours as false and harmful. I propose that kindness is a strength women need to be careful not to weed out of our gardens in order to play with the boys. And Cinderella depicts why this is true. As women, we may be inspired by and fall in love with the Katniss Everdeens of this world. When faced with unimaginable situations, we may hope to take up our arms and fight. At times this may be available to us; there are times when fighting openly and bitterly is in our power. But what about the many times that type of fight is not in our means? What about times when the forces are just too great and we are just too small to become Katniss? What if we are Cinderella? Are we really willing to say that the only strength that matters is the strength to fight? Or do we have a definition of female power that is both big and small enough to include kindness and perseverance in times of trial and duress? Part of the debate around the Disney princesses concerns what values we want to instill in our daughters. As a child and I teenager, I didn't resonate with Cinderella. I resonated with Belle, and Mulan, and Katniss, and Eowyn - the women who were strong and could put up a good fight. I am glad that I had these characters to look up to and be inspired by and I am thankful for parents who never dampened my love of them or tried to instill a singular vision of feminine virtue. I will give my future daughter these women to admire. And I will tell her to fight when and if the time is right. But I will also give my daughter Cinderella. And if my daughter is anything like me, I will give her Cinderella more than the other women, because kindness and perseverance are not my natural gifts. I want my daughter to know that strength is multifaceted. I want her to know that kindness is not weakness. I want her to know that serving the good of others does not mean giving up her agency. Most of all, I want her to know that like Cinderella, there may comes times in which she is not enough to beat the bad guys and when or if that happens, she will need to live in such a way that acknowledges their power but not her moral defeat. As I said above, there is only one Story that does not deserve revision - it is the single story for all ages. The point of this post is not that we should withhold doubt and reexamination from the stories we tell our daughters. What we tell them does shape them more than we can ever imagine. I just don't think our current version of Cinderella is one to do away with, for it rounds out and enlivens all that we want our little girls to grow up to be. ~Hannah

1 Comment

"We sometimes hear the expression 'the accident of sex,' as though one's being a man or a woman were a triviality. It is very far from being a triviality. It is our nature. It is the modality under which we live all our lives; it is what you and I are called to be - called by God, this God who is in charge. It is our destiny, planned, ordained, fulfilled by an all-wise, all-powerful, all-loving Lord."

Unless you're living under a rock, you know that gender is a big issue in today's world. A really big issue. I'm not convinced this is an entirely new phenomenon - history is full of humanity's attempts to clarify, assert, and remember what it means to be a man or a woman. But we are entering a time that is new for our collective consciousness, a time in which definitions and parameters are being directly challenged in ways unparalleled for the modern Western world. There are many ways Christians can respond to these changes, but two of the most common ways I observe among the community of faith are fear and accommodation. We all have friends and family members who are either rampaging about what the world is coming to or lamenting that the church remains so culturally outdated and judgmental. One side argues that nothing should change regarding our ideas of manhood and womanhood. The other side doesn't care if the popular culture dictates gender to be a sliding scale. Maybe you belong in one of these camps yourself. Instead of fear or accommodation, the most encouraging responses I've seen and the response I wish more people would take, is a celebration of the human being's design. Today America's younger generations love design. Good design is obsessed over and glorified. I've heard some of my most hip friends give good design an almost salfivic role in the world. Young America is in love with the idea of a curated life - a life which displays the careful consideration and design of a person making conscious decisions. We celebrate our own ability to carefully arrange the things around us, but somehow we don't have an appreciation of that which is above us in the design and curation of this world. The world has always been plagued by the divorce of the human being's wholeness. For millennia, humanity has held in one way or another to the sharp divide between our material and immaterial selves. In some ways, it's understandable. We feel a disjointedness between our bodies which every day underwhelm and disappoint us and the inner life that can be so rich and promising. But this is a false division, a feeling which is only that, and which betrays the brokenness of humanity. "No one can define the boundaries of mind, body, and spirit. Yet we are asked to assume nowadays that sexuality, most potent and undeniable of all human characteristics, is a purely physical matter with no metaphysical significance whatever. Some early heresies which plagued the Church urged Christians to bypass matter. Some said it was in and of itself only evil. Some denied even its reality. Some appealed to the spiritual nature of man as alone worthy of attention - the body was to be ignored altogether. But this is a dangerous business, this departmentalizing. The Bible tells us to bring all - body, mind, spirit - under obedience." Our materiality matters and it matters in our modern understanding of gender. We must let it speak to us, especially if we believe that there is a God who designs and curates the universe in which we live. Maybe my hipster friends are on to something - there is a lot of learn from their appreciation of and respect for design. They work to bring both the material and immaterial world into unity and submission to their plans. There are no "accidents," but rather chaos brought into beautiful harmony. Love is poured into their work, and labor, and they know even the smallest details of the worlds which they build. Everything has its role and purpose. And they celebrate it. As women, we need to celebrate the way we have been designed. This doesn't mean there is no debate or discussion about how to understand or interpret our design. For example, we no longer believe women shouldn't participate in athletic activity for fear our uteruses will fall out. This misunderstanding of the design caused centuries of discrimination and was rightly challenged and changed. But that doesn't mean there isn't a design. We can and should continue to anticipate that the material world which not only surrounds us, which indeed is us, has something to say about who we are. As Elizabeth Eliot finally asks us, "Yours is the body of a woman. What does it signify? Is there invisible meaning in its visible signs - the softness, the smoothness, the lighter bone and muscle structure, the breasts, the womb? Are they utterly unrelated to what you yourself are? Isn't your identity intimately bound up with the material forms? ...How can we bypass matter in our search for understanding the personality?" ~Hannah So... This is about one of the funniest things I think I've ever seen. And from my personal experience, it's spot on. Happy hump day, y'all. ~Hannah  I've read a couple of great posts recently and thought I would share. It's always exciting to find people either saying the things you want to say or saying things your mind simply isn't smart enough to think of. So here are some borrowed words on topics we love to discuss at Carved to Adorn. First, Ruthie found an amazing article over at First Things on Lena Dunham's Girls, Jane Austen's Mansfield Park, and the sacred stories we tell. Alan Jacobs's thoughts are chewy, but every bite is fantastic. "What we need is not condemnation of Adam, or condemnation of Hannah for liking Adam, but better art and better stories, better fictional worlds, by which I mean fictional worlds that rhyme with what is the case, with what is true yesterday, today, and forever. Not the abolition of mythic sandboxes but the making of sandboxes in which to play with true, or truer, myths: fictive spaces in which Hannah can do better than Adam, and Adam can be better than what he is, a bitter prisoner of past angers and resentments." Read it here. Second, in order to help keep the conversation about female sexuality going, I recommend Jordan Monge's post yesterday on Her.meneutics titled The Real Problem with Female Masturbation, Call It What It Is: Ladies Who Lust. I'm not sure that I agree with everything in it, but it is an honest discussion and a good place to start. Please add any thoughts you have about it to our comments! Lastly, since I'm sure we could all use a good laugh after reading the first two articles, I give you this to end on a lighter note. If you're like me and secretly wish you lived in an Anthropologie storefront, you will identify with these 87 thoughts. ~ Hannah Quoting Ruthie’s intro to her post last week:

“This is the kind of post that is addressed explicitly to Christians, and will be confusing and strange for many of my friends who are not Christians. So, secular friends, if you keep reading, you are about to get an intimate glimpse into one aspect of Christianity. And Christian friends: grace. Grace all around.” "Men enjoy sex more than women." Of all the conversations I had about sex during my adolescence, this phrase was the most important. Spoken by a trusted and authoritative source during a conversation about how a young teenage girl with a blossoming bosom should conduct herself, this comment shaped and formed much of my views on sex. It’s important to understand that the person making this statement was not in any way trying to denigrate sex. Actually, it was quite the opposite. As typical of orthodox Christian beliefs, he was speaking quite eloquently on the beauty of sex and how good a part of creation it is. The goodness of sex was the key reason why this man wanted his listeners to know that it should be protected and not treated carelessly. He made the above comment upon noticing the discomfort his female audience displayed, proceeding to explain that while women may not see certain issues concerning sex as a big deal, all men did. The tenor of this conversation is very familiar to most women my age who grew up in conservative Christian homes. We grew up with the idea that all men we encountered were loosely reigned-in hormonal torpedoes possible of being set off at a moment’s notice should we give any false encouragement. Now that I look back on adolescents, I actually think this very well may be true of most lads between the ages of twelve and twenty. I do not believe it was damaging to be told as a young woman about how much men are wired for sex or that how I act and dress can communicate certain unintended things. What I do lament as I look back upon my sexual awakening was the constant and pervasive idea that somehow keeping male sexuality in mind meant women do not like sex as much as men or that women do not struggle sexually as much as men. Because here was the problem - by the time I heard the above statement, I was already struggling greatly with my sexuality. I don't remember exactly how old I was, but I think I was about fourteen or fifteen. The reason I didn't feel comfortable with discussing the topic was not because I didn't like the idea of sex, but rather that I was terrified of how much my body did seem to like the idea of it. I truly believe many young women's reticence to talk about sex in our teenage years was not because weren’t interested in it. It was because sex seemed like a daunting and awe-some thing and we couldn't find the courage to speak up concerning the questions we had or the hormone induced feelings we were feeling. As I let the idea of men liking sex more than women sink further and further into my teenage psyche, the more and more confused I started to feel. I liked the idea of sex and I liked the sexual feelings I was feeling. Did that mean I was some kind of outlier of femininity? Was I somehow a dirty, over-sexualized woman because the idea of intercourse sounded great? I was convinced that I must have been way more sexually wired than every other good Christian woman I knew, and within my world, this did not seem like a positive thing. For me as a woman, ideas of sexual purity were somehow closely linked with sexlessness. Teenage male sexuality was recognized and addressed as a good and natural drive; male purity seemed to be defined as Christian restraint. For us young women, though, our own blossoming sex drives were mostly unacknowledged. Purity for us was about helping keep male sex drives in check rather than learning how to address our own rising desires. Male lust and masturbation were seen as natural inclinations out of place of what God intended. The idea of female lust and masturbation did not even exist. I saw these things play out with even more intensity at my small Christian college. The idea that women did not enjoy sex as much as men and therefore were more naturally pure continued to cause major confusion as young women entered and went through college. Sex was the primary topic that we all wanted to talk about, that we were all obsessed with, but hardly ever got to really engage on. When I look back on life in the female dorms, it seems like the sexual tension was so thick, it could have been cut with a knife. Though it may have looked different from the struggles of our male co-eds, I do not believe we women struggled any less with sexual issues. Porn was not an open problem at the time (though I'm guessing it would be more of one in today’s generation, at least statistically), but there were hardly any limits on what movies or tv shows girls felt they could watch. They had so imbibed the idea that they were more naturally pure that girlfriends frequently told me they didn’t think it mattered what they watched. I frequently and commonly heard women talk about men in ways that if the genders had been reversed would have been immediately called out as sinful lust. Young women, including myself, got away with this kind of openly sexual talk, again, because of our Christian culture's assumption that women do not struggle with lust as much as men. Female masturbation has been the absolute taboo topic of recent Christianity, (most people, male and female, simply do not want to believe that women have the type of sex drives that would be tempted by it), but I know it was very present within our dorms. Yet, even with all of these very real ways in which we young women were struggling with our sexuality during college, we never once stopped believing that we might not actually like sex itself. I'll never forget the time there was a panel discussion on the topic of sex at the college. I didn't attend it myself, but something was said by one of the panel members that threw all of my female friends into a tizzy worrying about whether or not they would like sex after getting married. One of my friends was engaged and I can still see the panic-stricken look on her face as she worried about what her future would hold. A few days later, a recently graduated and married friend visited campus and many of my friends fell upon her with questions about whether or not she liked sex. An open and unassuming person, she simply smiled widely with a glint in her eyes and said, "Yes. Very much. You have nothing to worry about." A loud collective sigh echoed throughout campus. Somehow, despite everything that almost every fiber of our bodies was telling us about our sexual desires, we needed convincing that it was possible for women to like sex. I never needed convincing that I would like sex, but I did need to understand that my sex drive did not make me less pure as a woman. I had many fears about sex going into marriage, but figuring out how to want sex was not one of them. It's sad to me now that I ever feared I was too sexual. How can that even be a thing? I and many of my dear friends often talked with each other about wanting to get married simply so we could have sex, but these conversations were always quiet and in private so that we would not seem like “those” type of women. It is a common idea within the Christian community that it’s good for men to get married so that they do not burn in lust, but who has ever heard women openly talk about the goodness of getting married for their own sexual needs? During the first few months of my marriage, I had a recurring experience after having sex with my husband. We would have a glorious experience, full of love and adventure, but when we finished, I would go and sit in the bathroom by myself. A few times I cried, but mostly I just sat as a certain wave of emotion rolled over me. I still can't name the emotion specifically, but there was a sense of emptiness and loneliness to it, along with a profound recognition of loss. It was similar to homesickness, but wasn't the same. I was not unhappy; I had just been exuberant. I was not ashamed; I have never been more sure and confident of my body. I was not really lonely; my husband is my best friend. The feeling stopped after a few months and the farther away from it I’ve come, the more I think it stemmed from the perceived loss of my sexual identity. Before marriage, Christian women have a certain and particular identity - sexless and pure. And now, all of the sudden, in the throws of marital passion, I was experiencing a profound and fundamental shift of identity. I was now a fully recognized sexual being in the eyes of my Christian subculture. During my times sitting in the bathroom, my soul was mourning the passage of my perceived purity. But how was I at all any less pure than before I was married? How was I any more a sexual being than before I was married? It seems to me that in our Christian views concerning sex, men simply go from being inactive sexually to active. Why is the change for women so much more fundamentally deep and dramatic? Because the Christian community tends to falsely believe that sexual purity for men is a matter keeping in check something that is already present, while for women, marriage is the turning on of a sex drive that shouldn’t have previously exist. Like men, women are sexual agents and the Christian community has got to start talking and acting like this is true. In a culture as saturated with sex as our is, we need our mothers, grandmothers, sisters, aunts, and dearest friends to be showing the younger generations that they are sexual beings who have something to say to us. Of course there are tasteful and dignified ways to do this, but there is nothing healthy about us pretending that sex is not an issue for women. Women want sex and we can either keeping telling them to deny their identities as sexual beings or we can start an ongoing conversation about the glories of female sexuality as God created it. So... let's talk about sex. ~Hannah Addendum: This post was getting really long, so I’m leaving it here for now. But this is a conversation we want to keep having at Carved to Adorn. I’m listing a few points below that I think would be beneficial for anyone to consider when taking up this topic and hopefully Ruthie and I can attempt to write about them in the coming months. First, Christian purity does not equal female sexlessness. Second, women and men may experience sex differently and prefer different aspects of it, BUT women do indeed love sex. Third, in most cases, good sex takes work, so if a woman does not enjoy it right away, it doesn’t say anything about her (or the gender as a whole’s) natural capacity to enjoy sex. The wisest and best women (and men!) know there are ways to increase your pleasure during sex. Fourth, women are not limited to liking sex when they are young, but rather they can and do love sex throughout the many different stages of life. If these points can start to be more a part of the general conversation concerning female sexuality, we will make long strides in helping women, young and old, embrace all that God made them to be. It seems that for the past six months my Facebook feed has been full of one contentious debate after another over topics relating to women. First there was the whole bikini debate, then the graceless-mom rant against teenage girls, and now the two articles double-timing Facebook called something like "Men and Woman Are Not Equal" and "Why Not to Educate Your Daughter" (full disclosure: I have not read any of the first and only parts of the second). It seems every time I open Facebook, some intense feud is raging between my friends concerning issues pertaining to womanhood.

My intention is not to address all of these debates right now. In general, I think they are all old, worn-out, and ridiculous. What I do want to talk about here is an observation I've recently made. It seems the vast majority of people posting these articles (and often writing them) are male. And what's more, they seem to always be posted with the express desire to get both men and women riled up. They are posted with seemingly benign introductory comments about discourse and soliciting opinions. After intense debate follows, the person posting makes an obligatory comment concerning his original good intentions and hoping nobody's feelings are hurt. But I often wonder if that's really what is going - is the man posting these things is really aiming for meaningful conversation or is he really just trying to collect kudos for how many people pay attention to what he posts? I know many men who are intelligent, gifted in conversation, and think very carefully and respectfully about the issues facing modern women and none of them post divisive articles to Facebook. If they truly want to see what people think about something controversial they have read, they do what any other grown up person does and have an actual face to face conversation about the issue. They are not motivated by clicks or likes or comments, but rather by the desire to edify and encourage both the men and women who struggle with these issues. Women, if you are wondering about modesty, education/career, family, and the millions of the other things that furrow our brows, please stop paying attention to the young male blogger or Facebook-er who just wants to see how many people he can get to stop by his page and turn instead to the person you respect most and ask his or her opinion. Please just pass over the pointless post because these men do not own the conversation on these topics. Honestly, they probably even barely had a voice in it until you helped give it to them! Men, please consider your motivations in posting these things. Honestly, what do you hope to gain? Are you trying to actually act for the good of others or are you just using these difficult topics to create more traffic in your corner of the social media world? Are you treating these issues like the extremely serious and weighty issues that they are for women the world around or are you flippantly stirring up emotions and hurt? What are your motivations? Until your motives are servant-like and gentlemanly, please stay away from the post button. Please. ~Hannah I first heard someone call God "Mother" in 2005 when I was studying in Washington, DC, during my junior year of college. What shocked me most was not the word itself, but the context. Growing up in university settings, my social circles were pretty diverse and concepts of the divine feminine were not new to me thanks to Hindu playmates and a neighbor who constructed a giant, papermache Mother Earth statue in the back yard for her high school graduation. No, what was shocking that year in DC was that the context was not the already familiar pagan one; rather, the word came from a classmate at an evangelical Christian study program. When it came to her turn to say a prayer before class one afternoon, my classmate started her prayer with "Father, Mother God..." After her address of God is such a manner, I can't remember another single word she said because I was so stunned at what I heard. To whom did she think she was praying?

Well, as usually happens, life kept on going, papers were still due, and I didn't give too much time to either thinking about what had happened or to getting to know this classmate whom I only occasionally saw. I returned from DC to my college outside of Chattanooga and forgot about it even further. But not for long. For my senior thesis in history, I decided to study early 20th century feminist sexual philosophy. It fascinated me and I loved delving into topics about which I had long been curious. Funnily enough, I also found myself in a theology class and the intersection of studying historic Christian doctrine while reading DeBeauvior and the Heterodites left me asking a slew of questions about where and how women fit into God's eternal plan. Why was my faith so male-centric? (This is a topic of vast width and depth, but for some of my initial thoughts on it from a while back, see here). Thankfully I had very wise professors who, rather than dismissing my questions, kindly pointed me in the direction of better questions and I was able to come to a place of peace and faith about having a Heavenly Father. But I still continue to think about and mull over these questions. Ultimately, the question that I have come to is this: Since God has chosen to reveal himself as our Father, what is the significance of this choice? But before coming to this question what I recognized, and what many other women will have to recognize, is simply that God has revealed himself using masculine language rather than feminine. And it is his prerogative. Before any conversation about where and how women fit into God's design and plan, we must first understand God's choice of language for himself. Now I am in seminary and finding plenty more opportunities to think about these questions. They are complex and they are wonderful questions. And they are challenging. Our God is not simple and he is not mild. Even in the midst of serious wrongs against and problems with women in the church, God's character does not alter and he is awesome in his beauty. Anyways, I wrote the following paper for a class and since I found the topic to be really interesting, I thought you all might find it interesting, too. I am not going to tout it as a great piece of research, but hopefully it can be a source of thought as we strive to know and love the God who created male and female and revealed himself as Father. ~Hannah P.S. I took out the footnotes for ease of reading on the blog, but left the bibliography. _______________________________________________________________________________ Naming the Divine: God’s Gender, Feminist Theology, and the Doctrine of Revelation 1. Introduction – Who Are We Talking About? In the last fifty years, feminist theologians have raised a number of fundamental questions about the nature of God. What started as an exploration of and outcry against the church’s history of misogyny led to efforts to see justice done by introducing feminine language for God. The feminist theologians have faced strong criticism from evangelical theologians. At stake within the debate is Christianity’s very understanding of God and his divine right of revelation. More fundamental to the debate are questions about God’s personhood. Whether they are content to maintain the label of Christianity or intent on wrecking the religion as a whole, the feminist theologians examined in this paper all take issue with the traditional orthodox understanding of who God is. This paper will discuss two of the most prominent feminist writers and the disregard for God’s right to reveal himself that underpins their writing. There are many different aspects to feminist arguments for gender inclusive language, but in this paper we will be analyzing the underlying views of God, particularly in the works of Virginia Mollenkott and Mary Daly. Rather than interacting with God according to the language he has chosen, these theologians’ take the right of naming God for themselves, either reducing God to a concept or claiming that the need for female inclusion outweighs God’s communication. The reclamation of the power to name was central to the feminist movement philosophically and these theologians openly talked of the need for renaming God. In response, we will consider how Christian doctrine has held for thousands of years that it is God who reveals himself to us. We do not create him, change him, or name him. As with any person, but especially with the eternal Person, it is not within our power, ability, or rights to alter what God has told us about himself. In response to the feminist theologians, we need to look to one of our most foundational doctrines and carefully consider its application. The starting point of our response must be God’s rightful revelation of himself – that God tells us about himself, names himself, and directs our language towards him. 2. Radical and Evangelical – The Feminist Theologians Feminism’s history with Christianity is long and complex. Feminism and Christianity have not always been oppositional, in contrast to the typical portrayal: many Christian denominations and organizations from the mid 19th century onward provided a home and support structure for various feminist movements. Serious feminist theology, however, did not begin until the late 1960s and started to take significant shape in the 1970s and 1980s. Though a simplified statement, the feminist theologians were initially divided into two groups – radical and evangelical feminists. Both groups believed in the importance and necessity of religion for the further good of women; however, they had very different ideas about what that meant. The evangelical feminists believed the gospel held the power necessary for female transformation and strove to find Biblical support and answers for their causes. The radical feminists were more diverse in their relationship with Christianity. As exemplified in Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow’s popular anthology of radical feminist theology, Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion, the radical feminists either desired to completely transform and alter the core of the Judeo-Christian tradition by looking back to what they claimed to be its roots, which incorporated goddess worship, or they considered themselves “post-Christian” and breaking beyond the boundaries of the Christian faith. Virginia Ramey Mollenkott initially found herself within the evangelical feminist movement and, though perhaps an unlikely candidate, was one of its leading voices. Mollenkott was raised in a strict fundamentalist setting and attended Bob Jones University for her undergraduate degree. She married straight out of school, but went on to complete a Masters and Doctorate in English while raising a family, not a small feat for a woman in the 1950s and 60s. After chairing the English department in a religiously affiliated college, Mollenkott quit her job and found a position at a secular institution in order to clear the way for what she felt to be an inevitable divorce. Shortly thereafter, Mollenkott started to become involved with the Evangelical Women’s Caucus, the center of evangelical feminism, and though Mollenkott’s relationship with evangelicalism eventually completely broke down due to dramatic shifts in her theology and personal life, her first two books on the topic of Biblical feminism had a huge impact. Mary Daly, who held a doctorate in each of the areas of religion, sacred theology, and philosophy, taught at Boston College and sat squarely within the radical feminist camp, if not at its head. One of the first feminist theologians to have a major impact, Daly came from the Catholic tradition, but openly rejected most, if not all, church doctrines. 3. Constructing the Feminine within the Divine A. Virginia Ramey Mollenkott Mollenkott’s arguments are marked as much by what they leave out as by that for which they argue. Apart from certain odd hermeneutical arguments concerning Paul’s writings on women, Mollenkott’s arguments for feminine language for God in Women, Men, & the Bible and The Divine Feminine: The Biblical Imagery of God as Female rely on her understanding of metaphor. The starting point of Mollenkott’s argument for using feminine language for God is that since God is neither male nor female, all language used for him is metaphorical in nature. She writes, “It is vital that we remind ourselves constantly that our speech about God, including the biblical metaphors of God as our Father and all the masculine pronouns concerning God, are figures of speech and are not the full truth about God’s ultimate nature.” From this point, she goes on to assume that because these Biblical metaphors do not capture God’s full nature, they can therefore be changed or altered. Mollenkott further argues that since the cultural context of the Bible should not be absolutized, the presence of feminine imagery for God shows us that the authors intended to encourage their listeners to conceive of God in feminine terms. Mollenkott argues in Men, Women, and the Bible that since the cultural setting of the Bible was strictly patriarchal, any presence of feminine imagery for God would have been a challenge to masculine conceptions of God and a statement on the acceptability of feminine language. She applauds the daring of the Biblical writers for referring to God in the feminine as much as they were able to, since given their cultural context they could not refer to God in feminine language more than they did. This idea forms the basis of her later book, The Divine Feminine, where she looks at a variety of passages with such images as birth pangs (Isaiah 42:14), Lady Wisdom (Proverbs 1-9), and a mother hen (Matthew 23:27) used in connection with God. Mollenkott’s underlying assumption is that it is humanity that names God. She correctly argues that all of the images used for God are inspired; yet she fails to recognize or acknowledge God’s revelation of himself. Mollenkott writes, “The Bible certainly utilizes male imagery concerning God, and Jesus encourages us to call God our Father, so there cannot be anything wrong with that. The problem arises when we ignore, as we have, the feminine imagery concerning God, so that gradually we forget that God-as-Father is a metaphor, a figure or speech, an implied comparison intended to help us relate to God in a personal and intimate way.” Mollenkott is very intentional to say that in interpreting the Bible, we must look for the author’s original intent; however, she does not seem to talk as if God is author behind those humanly involved. In Mollenkott language, primary Biblical authorship lies with the human author and as such, we have the freedom, and even responsibility, to change our language for God based upon current needs. B. Mary Daly In reading Daly’s groundbreaking works, The Church and the Second Sex and Beyond God the Father: Toward a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation, it is hard to escape the influence existentialist philosophy had on her view of God and religion. In The Church and the Second Sex, Daly directly credits Simone de Beauvoir with influencing much, if not all, of her arguments. In The Church and the Second Sex, de Beauvoir’s philosophy is a more direct influence and source for much of Daly’s criticism, but in Beyond God the Father, we see existentialist philosophy more fully thought out and applied to her deconstruction of Christianity. In these two books, we see Daly develop and bring to fullness her arguments for God as Verb and her ideas that transcendence for humanity lies in female liberation. By the end, Daly has taken away any possibility of God’s self-revelation. In The Church and the Second Sex, Daly starts her arguments with pretty traditional feminist criticisms of Christianity, such as skewering its misogynistic history, but she quickly moves on to interlace discussion of de Beauviour’s own criticisms and philosophy of gender. She integrates de Beauvior’s arguments that as an instrument of women’s oppression, the church has kept women in passive roles, prevented them from full participation, and taught them to focus on the after-life as compensation. Daly states, “…the Church by its doctrine implicitly conveys the idea that women are naturally inferior.” Daly then goes on to argue this can be most clearly seen in the doctrines of Mary. Women within the church were forced to abandon the mother-goddess of antiquity and in substitute were given the virgin Mother of God who continually exists in a role subordination. She criticizes what she sees as Greek influence in Christian thought which led to ideas of fixed natures and Jewish influence towards antifeminism. Daly’s most significant issue is with that of fixed natures. Echoing the existentialists, Daly writes in the The Church and the Second Sex that for woman to have her own personhood and freedom, she must be able to develop and define her own nature. Any idea of scripture informing or defining the nature of femininity or womanhood is abhorrent to Daly. She writes, “The characteristics of the Eternal Woman are opposed to those of a developing, authentic person, who will be unique, self-critical, active and searching…” and later “…on all fronts the Eternal Woman is the enemy of the individual woman looking for self-realization and creative expansion of her own unique personhood.” Because the church has argued the nature of gender is immutable and God revealed himself as male, woman cannot enter fully into personhood, so the source of immutable gender must be challenged. To do this, Daly offers a number of solutions. No one really believes God belongs to the male sex, but we continue to speak as such, so “conceptualizations, images, and attributes” of God must be altered. To do so, Christianity must first be de-Hellenized, or moved beyond ideas of omnipotence, immutability, and providence. Second, ideas of biological nature or Natural Law must be ridden as part of the larger need to do away with a static worldview. Third, Christianity must move beyond institutionalism and fourth, beyond ideas of sin. But most importantly for our discussion, Daly calls for the end of the idea of a closed and authoritative revelation. Daly develops her ideas further in her follow up Beyond God the Father. Because of Daly’s views on revelation and scripture, she sees no separation between what the church has been or said and what the Christian view on women is. She says, “The symbol of the Father God, spawned in the human imagination and sustained as a plausible by patriarchy, has in turn rendered service to this type of society by making its mechanisms for the oppression of women appear right and fitting.” God is not above or separate from his people, therefore what the church has said and what the scriptures say are not separated in their implications for women. This is the heart behind Daly’s infamous statement, “…if God is male, then the male is God.” From this point, Daly has very few pretenses of staying within the bounds of Christianity or of relating to the God who reveals himself. Her purpose is to find transcendence and “the search for ultimate meaning and reality, which some would call God.” Key to her argument is the rejection of God as a person to be known. In her view, religion no longer has a relational nature to it and as such there is no God who tells us anything about himself. Without the concept of revelation, the concept of God can be dismantled and rebuilt according to a person or group’s needs. She says, “The various theologies that hypostatize transcendence, that is, those which one way or another objectify ‘God’ as a being, thereby attempt in a self-contradictory way to envisage transcendent reality as finite. ‘God’ then functions to legitimate the existing social, economic, and political status quo, in which women and other victimized groups are subordinate.” And, “I will begin my description with some indications of what my method is not. First of all it obviously is not that of a ‘kerygmatic theology,’ which supposes some unique and changeless revelation peculiar to Christianity or to any religion. Neither is my approach that of a disinterested observer who claims to have an ‘objective knowledge about’ reality. Nor is it an attempt to correlate with the existing cultural situation certain ‘eternal truths’ which are presumed to have been captured as adequately as possible in a fixed and limited set of symbols. None of these approaches can express the revolutionary potential of women’s liberation for challenging the forms in which consciousness incarnates itself and for changing consciousness.” Daly goes on to argue that we should no longer conceive of God as a noun, but rather as a verb, or rather God as Verb. She believes all ideas of God as a person are anthropomorphic, and that hope for women lies in beginning to see God as “Be-ing” in which we can and should participate. She writes, “Women now who are experiencing the shock of nonbeing and the surge of self-affirmation against this are inclined to perceive transcendence as the Verb in which we participate – live, move, and have our being.” Furthermore, the power of naming must be restored to women in addition to participation in the transcendence, or being, of God. This includes the power of naming God. Daly writes, “To exist humanly is to name the self, the world, and God. The ‘method’ of the evolving spiritual consciousness of women is nothing less than this beginning to speak humanly – a reclaiming of the right to name. The liberation of language is rooted in the liberation of ourselves.” Along with God’s being, his name is no longer something revealed, but rather something constructed and reclaimed by womanhood. 4. The Doctrine of Revelation After looking at these arguments, one may ask what an orthodox response should be. Of course, there are many more aspects to these women’s arguments that are not covered in this paper. But I have chosen to look closely at views on revelation because the fundamental question we need to ask is if we are talking about the same God. Who are Daly and Mollenkott talking about? I would propose that unless they are talking about a God who has revealed himself on his own terms, the discussion is about a false god. It is a basic tenant of Christianity that God’s transcendence sets the precedence for our relating to him. In Knowing God, J.I. Packer starts his book with a wonderful observation on the nature of relating to God. He writes, “… the quality of extent of our knowledge of other people depends more on them than on us. Our knowing them is more directly the result of their allowing us to know them than of our attempting to get to know them… Imagine, now, that we are going to be introduced to someone whom we feel to be ‘above’ us… The more conscious we are of our own inferiority, the more we shall feel that our part is simply to attend to this person respectfully and let him take the initiative in the conversation.” If we really believe there is a transcendent God, then we must rely upon what he tells us about himself. We may not understand or like it, or we may see grave misinterpretation by the church of what he has told us, but we are completely dependent on God’s communication of himself to us. In his book on the topic called The Revelation of God, Peter Jensen ties our ability to pray to God to the name by which he reveals himself. Apart from God’s revelation of how we should call upon him, all spiritual relationships are sinister and deceitful. He writes, “Throughout the Bible, our speech directed towards God is understood to be an essential part of this friendship with God. Prayer is virtually a universal human phenomenon, but Christian prayer takes its nature from what we know about God, including the invitations to prayer that he gives us. The prayers of the Bible, including those of Jesus, show that prayer responds to the revelation of God in his word. Its scope, content, and assurance are based on the character of God as he reveals himself. Confident prayer is based on knowing God’s name. As far as Christians are concerned, God is characteristically addressed as Father, in the name of the Son and in the power of the Spirit. This trinitarian intimacy arises from an encounter with the words God has spoken. The Bible does not regard those who are ignorant of God as lacking spiritual relationships, but considers that those relationships are sinister rather than helpful. What Israel in particular has been given is the name of God, by which God’s people may address him with success, in that they may be confident of being heard. Without the name, relationship is impossible. Prayer moves within the ambit of revelation…” In prayer, our most intimate interaction with God, we are told to call God our Father and it is not within our rights or abilities to change this fundamental requirement for relating to God. If it is up to God to reveal himself to us, then we must assume that though the feminist theologians were correct in arguing that God is neither male nor female, they were incorrect in arguing male language for God is optional. In his Christian Theology, Millard J. Erickson says, “Humans cannot reach up to investigate God and would not understand even if they could. So God has revealed himself by a revelation in anthropic form. This should not be thought of as an anthropomorphism as such, but as simply a revelation coming in human language and human categories of thought and action.” If we accept that even God’s anthropic language about himself is revealed, then we do not have the liberty to change the gender of the language used. Erickson also says of God, “The particular names that the personal God assumes refer primarily to his relationship with persons rather than with nature.” We may believe that God is Spirit, and therefore neither masculine nor feminine, but we must believe that his choice to use masculine language and teach us to call him Father was for a relational purpose with his people. 5. Conclusion – Why Should Revelation Matter for Feminism? As the feminist theologians accurately assessed, naming is power. It is not something one does to another unless they have the right to do so and hold a significant degree of authority over the other. The right to name belongs to only a select group of people in this world, parents and the self, and the latter only in renaming. For a disenfranchised group to be empowered, the ability to name is an important right to establish. In Daly’s aggressive linguistic arguments to erase God’s personhood and Mollonkott’s more seemingly benign arguments using various Biblical imagery to refer to God in feminine language, both of these women recognize and lay claim for women to the primal power there is in naming the divine. What the feminist theologians disregard is the fact that it is not their right to rename the transcendent God. By doing so, as Jensen implies, both Daly and Mollenkott break the “friendship with God” that he forges with humanity through his name. God will not be wrestled into a new identity because of the very real injustice done to women; rather, he first demands relationship according to his will, and then promises freedom and restoration. The issues addressed by the feminist theologians are real ones and as such, Christians should participate in the conversations surrounding feminism; however, we must remember in doing so that God is not a concept to be changed for the benefit of humanity. God is the transcendent, triune Person about whom we can know nothing unless he reveals himself. In this, we should find hope because this Person who tells us about himself is all-powerful and just. The God who Is tells us about himself and he tells us that he will put to right all that has been wrong. Bibliography: Christ, Carol P., and Judith Plaskow, ed. Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1979. Cochran, Pamela D.H. Evangelical Feminism: A History. New York: New York University Press, 2005. Daly, Mary. Beyond God the Father: Toward a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation. Boston: Beacon Press, 1973. Daly, Mary. The Church and the Second Sex. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1968. Erickson, Millard J. “God’s Particular Revelation.” In Christian Theology, 200-223. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 1983. Erickson, Millard J. “The Greatness of God.” In Christian Theology, 289-308. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 1983. Jensen, Peter. The Revelation of God. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 2002. Mollenkott, Virginia Ramey. The Divine Feminine: The Biblical Imagery of God as Female. New York: Crossroad, 1983. Mollenkott, Virginia Ramey. Women, Men, and the Bible. Nashville: Abingdon, 1977. Mossman, Jennifer, ed. Reference Library of American Women, Volume I. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Research, 1999. Packer, J.I. Knowing God. Downer’s Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1973. |

Archives

October 2018

Categories

All

|