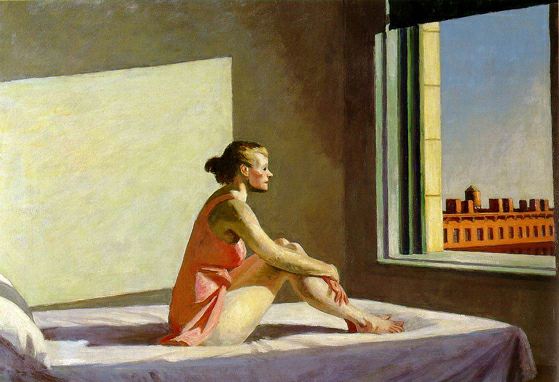

Hi friends. So I know in the grand scheme of things I haven't been married that long - only four years. If anything I say here seems totally out of whack to those who have been married longer, please let me know. Recently I've been thinking about when sex is the worst. And this is what I've come up with: sex is the worst when I want to be worshipped. My husband and I have a really great sex life. I haven't shared notes with others, but I personally consider ourselves as having a good sex life because a) we like to have sex with each other, and b) we find sex with each other interesting and satisfying. I'm sure there are more clinical definitions of a good sex life out there, but to my mind I'm not sure what more I could really want. Nine times out of ten sex is great. But I've recently been thinking about those tenth times and wondering what leads to them. Of course there are the obvious factors - one or both of us is tired, or someone ate too much ice cream and is bloated. But even those really obvious factors don't explain why sometimes sex just can fail to be what I know it to be most of the other times. Tiredness and gas produce laughter and mutual sympathy, but sometimes there is something else - something that creates distance and separation. During those times sex just feels off. It feels like I am looking for something I can't get and as a result, I become petty and demanding. Why can't my husband treat me in a certain way? Why doesn't he do this? If we want to get down to the nitty gritty, it usually looks like me hoping he would start doing things like writing poetry, staring ceaselessly at me, weeping at my very ravishing presence. You get the idea. In short, why won't he fulfill all of my romantic aspirations (that I usually don't give squat about, but matter terribly when I'm in that certain kind of mood)? Surely something is wrong with him. I went through one these bouts some time ago, and I kept growing more frustrated until one night it struck me - what I wanted was to feel worshipped in sex. I was suffering and making Trey suffer with me because, really at the end of the day, what I wanted was for sex, and everything leading up to it, to make me feel exalted and nothing short of glorified. Which, after all, is the backbone of all romantic thought. Haven't all of our stories told us that this is what sex should do - make you feel like the sole person in the world that matters? That a natural part of sex (especially for women) is the idea that your partner will be consumed by your very ravishing presence? Shouldn't my husband be literally going out of his mind just to be with me? I can't speak for men, but as I've been thinking over these past few weeks, I find the above to be particularly true for women. Just think about it. Whatever perspective the story might come from - traditional, feminist, something in between - the climax of a romance is usually when the man becomes so hot and bothered by the woman that he can't get her out of his mind. Then they have sex (I'm counting more traditional narratives that end with a wedding). Women love that image, but what is it that they love about it? Is it the sex? No, it's what the sex represents - that the man has fallen at her feet, so distracted by her that the world must wait. Most romances kindle sexual appetite far less than they kindle the desire to be the center, the focus, and the purpose of another person's attention. And that is a bad recipe for sex. When I think about the good sex we've had it has never had anything to do with how much Trey is falling at my feet, and everything to do with how much we are giving to each other. In fact, many of those times have been a surprise, coming at times when sex is simply the result of fun companionship or when we are sharing one another's burdens. In short, sex is the best when I am not waiting for Trey to be breathlessly overcome by me. The wife of the pastor who married us once told me that sex was best when both partners were working to please the other. I agree with her, but I also have had to learn that this statement doesn't necessarily mean a loss of self in sex. Rather I think it has more to do with understanding the self as with and for the other. It simply means that sex is an act of companionship, of mutual play and enjoyment. It is not an act of worship. In a world influenced by discussion of the male gaze we are attempting to teach men not to view women as objects, but on the flip side, are we teaching women not to view themselves as idols to be put on a pedestal? During a recent trip to NYC, I saw The King and I on Broadway and started rereading Louisa May Alcott's An Old Fashioned Girl. These Victorian and 1950s cultural relics clearly articulate that women are deserving of breathless adoration, but I was surprised when a few days after getting home I introduced Trey to When Harry Met Sally and found the same general idea. These three stories all have very different views on sexual expression; but they all share a common idolization of women, encouraging us to see ourselves as something to be got. I am actually pretty traditional in my views of men and women. I think it's good for men to value women and to treat them with respect. I like being wooed. But there is a difference between respect and reverence, and that difference can set a woman up for success or failure in the bedroom. Women, we are not made to be revered. Sex really isn't different than anything else in life, and I for one have found that desiring reverence does not work well for me in just about every other area of life. Just like it does in relationships, work, relaxation, etc., if you're anything like me, the desire for reverence, or worship, will most likely kill your sexual appetite, rather than fuel it. One of my all time favorite quotes is from Charlotte Perkins Gilman. She says, "Here she comes, running, out of prison and off pedestal; chains off, crown off, halo off, just a live woman." Gilman wrote these words in critique of Victorian ideals, and I find them to be applicable today in my sex life. I don't need Trey to give me a crown or a halo to have great sex. I simply need to run to him as I am - a live woman. ~ Hannah

0 Comments

I was recently remembering a few shocking conversations I had about love in the months leading up to my engagement to Trey. As with everyone seriously considering whether or not to marry a particular person, I was having a challenging time really knowing if I loved my boyfriend, so I occasionally asked married friends when they knew they loved their spouses. Most of the answers I received were pretty standard, pat answers. And by now, I've forgotten every one of those answers. Except for two.

My brother got married a year before I did. He had been pursuing the same girl for seven years, since the middle of high school. I figured that if anyone understood knowing when you love someone, it was him. So one summer afternoon while I was feeling particularly stressed over my relationship, I found him out on my parents' hot and stuffy third floor and asked when he had known he loved my now sister-in-law. In typical fashion, my brother cut straight to the chase. "I knew I loved Bethany when I asked her to marry me." I was shocked and incredibly displeased with the answer. I told him to make sure Bethany never heard him talk like that, but he laughed at me. I pushed for for further explanation and he struggled to go into more detail. But eventually he landed on telling me that you don't really love someone until you decide to love him or her. Romance and dating have uncountable feelings associated with them, but love doesn't exist without the decision to love. His answer didn't really satisfy me, but I left with a lot to mull over. Sometime later that summer, I was out for coffee with an acquaintance. We weren't close friends, but we talked for a long time about my dating life and whether Trey and I would get married. I asked her the same question - when did she know she loved her husband? Without any hesitation, she bluntly answered, "I fell in love with him when we got married." Again, I was shocked. If I remember correctly, I almost choked on my coffee. How could anyone give such an answer? How could anyone give it as shamelessly as she did? She wasn't embarrassed to make such a statement. She didn't blush and say, "It's kind of sad, and one of my biggest regrets, but sadly, I didn't really love my husband until we got married." No, instead she was honest, forthright, and giggled! This was her experience and she wasn't shy about it. Along with my brother's answer, I was now very confused. But I didn't immediately dismiss these thoughts. I continued to contemplate these answers and ponder over their meaning. By the end of the summer, I had agreed to marry Trey. I still didn't feel like I had great insight to the definition of love, and I sometimes felt fearful that I didn't know what it meant to love someone enough to marry him. But I knew I wanted to marry Trey, even if I still felt confused. I didn't doubt that I wanted to marry this particular man and spend my life with him. But I couldn't quite put a finger on whether I knew, really knew, that I loved him. Marrying my husband was the single greatest step of faith I have made thus far in my life. Not because I didn't deeply respect, or enjoy, or feel attracted to him. But because, as with all skeptics, I didn't feel like I could know what love for him really was. Looking back on the first six months of our marriage is looking back on one of the strangest times of my life. In so many ways, those six months were magical. Truly some of the best times of my life. We were long-distance for the entirety of our dating and engagement, so simply being in the same place brought with it a certain kind of heady joy. Everything seemed so relaxed now that we could just sit next to each other on the couch and watch TV, rather than talking on the phone every night. Being in each other's physical presence was a treat. Discovering sex together was incredible. Not incredible because it was instantaneously everything it would ever become, but because it was the entrancing exploration of virginal youth. Even fighting together was good. It was painful, and at times bitter, but it was good, so good to be working towards unity and understanding, laying the foundation of our lives together fight by fight. And yet, throughout all of this wonder and growth, I was still nagged by the question, "Do I really love Trey? And if I do, how do I know I do?" This question that lingered on in my mind was the single most difficult part of my first year of marriage. I didn't think about it often, but sometimes it would enter my head late at night as I tried to fall asleep. Or when I felt incredibly homesick and wanted to go home to my family. Or when a fleeting attraction to another man crept across my consciousness. It wasn't rational, and it wasn't predictable, but every now and then this question would arise and it would leave me deeply disturbed, sometimes for days. I wish I could tell you about the one spectacular thing that completely erased this question from my mind. Instead, it was a totally random and quiet night. I can't even recall what took place that day. But one night about six months into our marriage, I lay in bed as Trey fell asleep as I asked myself the same question I had been asking for almost two years. "Do I love Trey? Do I know that I love Trey?" And without any hesitation or any explanation, I knew that, yes, I loved this person more deeply and more truly than I had ever loved another person before. I knew that this new certainty didn't invalidate or belittle the love that I had felt for him before. But as an intense warmth of emotion washed over me, I knew I had reached a new place in our relationship. I wanted to love him, not just be married to him, or have sex with him, or enjoy life with him, but I wanted and decided to love him. And so I did. Being the internal processor that I am, I never told Trey about any of this until sometime this past year. One day I tentatively told him that I didn't think I really, truly loved him until after we were already married. It didn't surprise him and he kind of laughed when he heard it. He knows me in ways he himself often doesn't understand. We celebrated our third anniversary in May. I've been thinking a lot about how hard it was for me to know if I loved my husband and how simple the answer to that question now is. I've been thinking a lot about the difference between knowing you want to marry someone and knowing you love them. I've been thinking a lot about my culture's inability to distinguish between the two and how much that stunts my generation's ability to healthily consider marriage. I've been thinking a lot about how previous generations lauded the growth of love, describing it as a blossoming flower - there, in existence, but needing to grow beyond the bud into its full glory. Love is not something that comes upon you, but rather it is something you choose, and once the choice is made, it springs open into a radiant splendor. I love you, Trey Nation. I know I do. ~ Hannah  I recently finished reading Wendy Shalit's A Return to Modesty: Discovering the Lost Virtue. It was interesting. A lot of things jumped out immediately. For starters, the book is almost twenty years old and it definitely feels dates at points. She references pop culture quite a lot and everything surrounding date rape, gang rape, hazing, cat-calling, etc. reveals the book's age. Another point of interest is that Shalit is Jewish. Though I don't know where she is religiously now, at the time she wrote the book, she was not Orthodox, sort of. She is definitely enamored with many things stemming from Orthodox Judaism, but she never centers herself within it. As a Christian, this makes her voice really interesting since it's hard to map her ideas over one-to-one with a lot of what is said within conservative Christianity. Lastly, she is overly confident that what she says are obvious to womankind. Her book takes that tone of "all-people-secretly-know-this-and-when-it's-brought-into-the-light-they-will-rejoicingly-forsake-their-ways" that I find so irritating. Most people think they are acting consistently, logically, and morally, so I find any argument unconvincing that assumes people are simply blind. Yet, at the end of the day, I have to give it to Shalit. She wrote a book about modesty that is actually philosophically engaging. How many women exist that can claim that? I disagreed with her on quite a lot, but I would recommend anyone interested in thinking about the topic of modesty to read this book. Unlike just about any conversation I've heard on the topic, Shalit does not stoop to the level of bikinis and yoga pants. Instead, she asks America to engage the topic as one with philosophical depth. Unlike so many of the Evangelical debates that get stuck in the corner of male lust and whether or not women have a role to play in taking responsibility for such lust, Shalit addresses modesty as it actually should be addressed - as a sexual virtue. Her intended audience is not mother's trying to protect teenage boys from themselves or men who don't know how to keep their eyes off their friends' wives; rather, Shalit is writing to the completely secular female college grad who has spent her adult life sleeping around. If my memory serves me right, Shalit doesn't address clothing hardly at all. What she does address is the cultural, ethical, and philosophical milieu in which we live that tells young women they have nothing to protect sexually. The core of Shalit's argument is that modesty is essentially about privacy. Modesty is about maintaining the right to keep to one's self what one chooses. Connected to this is the natural right to make a big deal out of our sexual selves, and our sexual activity. In Shalit's mind, the the loss of modesty in Western society started with the reduction of the gravity of sex. She argues that women naturally treat sex as a big deal and modesty is our natural desire to protect what we believe to be important. Anything that trivializes or reduces the importance of sex, anything that tells women it is "no big deal" is a direct attack on a woman's right to protect her sexual self. Shalit meticulously argues that this is what is under attack in our society today. From classroom sex ed that forces young boys and girls to discuss their development and activity publicly to the common idea that women struggle with "hang ups" sexually if they do not respond in kind to men, Shalit argues that women today have been stripped of their natural tendency to modesty. By telling young teens to be casual and open about their sexual world, particularly by telling young women not to care so much about romantic notions concerning sex, our society is harming women's natural tendencies to protect themselves. Shalit gets a lot wrong, especially in her historical analysis and her romanticization of gender relations in the past, but the Evangelical world would greatly benefit from thinking about modesty along Shalit's lines of thought. In the end, her analysis is right. Modesty is ultimately not about preventing men from committing certain sexual sins. Modesty is about much more fundamental issues. However it is culturally defined, modesty is about the basic right and need of a woman to keep her sexual self as her own, bequeathing the right to share in it only to the beloved of her choosing. Despite all of the talk and hoopla about a woman's body belonging to herself, Shalit demonstrates that the Western world is increasingly and steadily redefining its sexual ethic to establish women's bodies as public entities. In the Evangelical world, all of our arguments about bikinis and yoga pants echo such changes. What we need is not detailed arguments about particular items of clothing, but rather a reexamination of some of the most basic principles. The question is not whether we as women are protecting our brothers, but rather whether we as women are keeping what we want to ourselves? ~ Hannah "We sometimes hear the expression 'the accident of sex,' as though one's being a man or a woman were a triviality. It is very far from being a triviality. It is our nature. It is the modality under which we live all our lives; it is what you and I are called to be - called by God, this God who is in charge. It is our destiny, planned, ordained, fulfilled by an all-wise, all-powerful, all-loving Lord."

Unless you're living under a rock, you know that gender is a big issue in today's world. A really big issue. I'm not convinced this is an entirely new phenomenon - history is full of humanity's attempts to clarify, assert, and remember what it means to be a man or a woman. But we are entering a time that is new for our collective consciousness, a time in which definitions and parameters are being directly challenged in ways unparalleled for the modern Western world. There are many ways Christians can respond to these changes, but two of the most common ways I observe among the community of faith are fear and accommodation. We all have friends and family members who are either rampaging about what the world is coming to or lamenting that the church remains so culturally outdated and judgmental. One side argues that nothing should change regarding our ideas of manhood and womanhood. The other side doesn't care if the popular culture dictates gender to be a sliding scale. Maybe you belong in one of these camps yourself. Instead of fear or accommodation, the most encouraging responses I've seen and the response I wish more people would take, is a celebration of the human being's design. Today America's younger generations love design. Good design is obsessed over and glorified. I've heard some of my most hip friends give good design an almost salfivic role in the world. Young America is in love with the idea of a curated life - a life which displays the careful consideration and design of a person making conscious decisions. We celebrate our own ability to carefully arrange the things around us, but somehow we don't have an appreciation of that which is above us in the design and curation of this world. The world has always been plagued by the divorce of the human being's wholeness. For millennia, humanity has held in one way or another to the sharp divide between our material and immaterial selves. In some ways, it's understandable. We feel a disjointedness between our bodies which every day underwhelm and disappoint us and the inner life that can be so rich and promising. But this is a false division, a feeling which is only that, and which betrays the brokenness of humanity. "No one can define the boundaries of mind, body, and spirit. Yet we are asked to assume nowadays that sexuality, most potent and undeniable of all human characteristics, is a purely physical matter with no metaphysical significance whatever. Some early heresies which plagued the Church urged Christians to bypass matter. Some said it was in and of itself only evil. Some denied even its reality. Some appealed to the spiritual nature of man as alone worthy of attention - the body was to be ignored altogether. But this is a dangerous business, this departmentalizing. The Bible tells us to bring all - body, mind, spirit - under obedience." Our materiality matters and it matters in our modern understanding of gender. We must let it speak to us, especially if we believe that there is a God who designs and curates the universe in which we live. Maybe my hipster friends are on to something - there is a lot of learn from their appreciation of and respect for design. They work to bring both the material and immaterial world into unity and submission to their plans. There are no "accidents," but rather chaos brought into beautiful harmony. Love is poured into their work, and labor, and they know even the smallest details of the worlds which they build. Everything has its role and purpose. And they celebrate it. As women, we need to celebrate the way we have been designed. This doesn't mean there is no debate or discussion about how to understand or interpret our design. For example, we no longer believe women shouldn't participate in athletic activity for fear our uteruses will fall out. This misunderstanding of the design caused centuries of discrimination and was rightly challenged and changed. But that doesn't mean there isn't a design. We can and should continue to anticipate that the material world which not only surrounds us, which indeed is us, has something to say about who we are. As Elizabeth Eliot finally asks us, "Yours is the body of a woman. What does it signify? Is there invisible meaning in its visible signs - the softness, the smoothness, the lighter bone and muscle structure, the breasts, the womb? Are they utterly unrelated to what you yourself are? Isn't your identity intimately bound up with the material forms? ...How can we bypass matter in our search for understanding the personality?" ~Hannah These two articles are spot on and they are excellent food for thought. I've found them deeply challenging and hope you do two. We simply have to rethink what it means to be the church. Period.  Click to read full article Click to read full article "Do you realize what you’re asking of me? I did. I was asking him not to act on his same-sex desires, to commit to a celibate lifestyle, and to turn away from an important romantic relationship. Yet as I reflect on that discussion, I now realize I didn’t fully understand what I was asking of him. I was asking him to do something our church community wasn’t prepared to support. I was asking him to make some astonishing and countercultural decisions that would put him out of step with those around him. In many ways, I was asking him to live as a misfit in a community that couldn’t yet provide the social support to make such a decision tenable, much less desirable. No wonder he walked away... The sexual demands of discipleship will become more plausible and practical to our gay (and straight) single friends if they see everyone in the community taking seriously all the demands of the gospel, not just the sexual ones."  Click to read full article Click to read full article "Today, whenever I listen to “Whole Again” or “Undo Me” or the spine-tingling “Martyrs and Thieves,” I’m sad. Sad because of the painful choices Jennifer’s parents made in the name of “self-discovery” and “self-expression” that led to harmful repercussions in the lives of their children. Sad because evangelicalism’s lack of ecclesiology and reliance on experience has led to so many strange and harmful expressions of faith. Sad because even though Jennifer had the integrity to be honest about her life rather than continue to make money under false pretenses, she received ridicule and insults from Christians she once wrote for. Sad because of the way faith gets privatized to the point that the exclusive Savior’s inclusive call to repentance seems too narrow a road to freedom. Sad because evangelicals are so quick to catapult converts into the limelight before they’ve had time to grow in wisdom and truth. Sad because of the pain many of our gay and lesbian neighbors have endured within a church culture that calls sinners to repentance but not the self-righteous. Sad because, apart from affirming her sexuality, I can’t see any way that Jennifer would think someone could love her. Sad because many Christians find it easier to love positions rather than people, while others believe it is impossible to love people without adopting their position." ~Hannah  I've read a couple of great posts recently and thought I would share. It's always exciting to find people either saying the things you want to say or saying things your mind simply isn't smart enough to think of. So here are some borrowed words on topics we love to discuss at Carved to Adorn. First, Ruthie found an amazing article over at First Things on Lena Dunham's Girls, Jane Austen's Mansfield Park, and the sacred stories we tell. Alan Jacobs's thoughts are chewy, but every bite is fantastic. "What we need is not condemnation of Adam, or condemnation of Hannah for liking Adam, but better art and better stories, better fictional worlds, by which I mean fictional worlds that rhyme with what is the case, with what is true yesterday, today, and forever. Not the abolition of mythic sandboxes but the making of sandboxes in which to play with true, or truer, myths: fictive spaces in which Hannah can do better than Adam, and Adam can be better than what he is, a bitter prisoner of past angers and resentments." Read it here. Second, in order to help keep the conversation about female sexuality going, I recommend Jordan Monge's post yesterday on Her.meneutics titled The Real Problem with Female Masturbation, Call It What It Is: Ladies Who Lust. I'm not sure that I agree with everything in it, but it is an honest discussion and a good place to start. Please add any thoughts you have about it to our comments! Lastly, since I'm sure we could all use a good laugh after reading the first two articles, I give you this to end on a lighter note. If you're like me and secretly wish you lived in an Anthropologie storefront, you will identify with these 87 thoughts. ~ Hannah Quoting Ruthie’s intro to her post last week:

“This is the kind of post that is addressed explicitly to Christians, and will be confusing and strange for many of my friends who are not Christians. So, secular friends, if you keep reading, you are about to get an intimate glimpse into one aspect of Christianity. And Christian friends: grace. Grace all around.” "Men enjoy sex more than women." Of all the conversations I had about sex during my adolescence, this phrase was the most important. Spoken by a trusted and authoritative source during a conversation about how a young teenage girl with a blossoming bosom should conduct herself, this comment shaped and formed much of my views on sex. It’s important to understand that the person making this statement was not in any way trying to denigrate sex. Actually, it was quite the opposite. As typical of orthodox Christian beliefs, he was speaking quite eloquently on the beauty of sex and how good a part of creation it is. The goodness of sex was the key reason why this man wanted his listeners to know that it should be protected and not treated carelessly. He made the above comment upon noticing the discomfort his female audience displayed, proceeding to explain that while women may not see certain issues concerning sex as a big deal, all men did. The tenor of this conversation is very familiar to most women my age who grew up in conservative Christian homes. We grew up with the idea that all men we encountered were loosely reigned-in hormonal torpedoes possible of being set off at a moment’s notice should we give any false encouragement. Now that I look back on adolescents, I actually think this very well may be true of most lads between the ages of twelve and twenty. I do not believe it was damaging to be told as a young woman about how much men are wired for sex or that how I act and dress can communicate certain unintended things. What I do lament as I look back upon my sexual awakening was the constant and pervasive idea that somehow keeping male sexuality in mind meant women do not like sex as much as men or that women do not struggle sexually as much as men. Because here was the problem - by the time I heard the above statement, I was already struggling greatly with my sexuality. I don't remember exactly how old I was, but I think I was about fourteen or fifteen. The reason I didn't feel comfortable with discussing the topic was not because I didn't like the idea of sex, but rather that I was terrified of how much my body did seem to like the idea of it. I truly believe many young women's reticence to talk about sex in our teenage years was not because weren’t interested in it. It was because sex seemed like a daunting and awe-some thing and we couldn't find the courage to speak up concerning the questions we had or the hormone induced feelings we were feeling. As I let the idea of men liking sex more than women sink further and further into my teenage psyche, the more and more confused I started to feel. I liked the idea of sex and I liked the sexual feelings I was feeling. Did that mean I was some kind of outlier of femininity? Was I somehow a dirty, over-sexualized woman because the idea of intercourse sounded great? I was convinced that I must have been way more sexually wired than every other good Christian woman I knew, and within my world, this did not seem like a positive thing. For me as a woman, ideas of sexual purity were somehow closely linked with sexlessness. Teenage male sexuality was recognized and addressed as a good and natural drive; male purity seemed to be defined as Christian restraint. For us young women, though, our own blossoming sex drives were mostly unacknowledged. Purity for us was about helping keep male sex drives in check rather than learning how to address our own rising desires. Male lust and masturbation were seen as natural inclinations out of place of what God intended. The idea of female lust and masturbation did not even exist. I saw these things play out with even more intensity at my small Christian college. The idea that women did not enjoy sex as much as men and therefore were more naturally pure continued to cause major confusion as young women entered and went through college. Sex was the primary topic that we all wanted to talk about, that we were all obsessed with, but hardly ever got to really engage on. When I look back on life in the female dorms, it seems like the sexual tension was so thick, it could have been cut with a knife. Though it may have looked different from the struggles of our male co-eds, I do not believe we women struggled any less with sexual issues. Porn was not an open problem at the time (though I'm guessing it would be more of one in today’s generation, at least statistically), but there were hardly any limits on what movies or tv shows girls felt they could watch. They had so imbibed the idea that they were more naturally pure that girlfriends frequently told me they didn’t think it mattered what they watched. I frequently and commonly heard women talk about men in ways that if the genders had been reversed would have been immediately called out as sinful lust. Young women, including myself, got away with this kind of openly sexual talk, again, because of our Christian culture's assumption that women do not struggle with lust as much as men. Female masturbation has been the absolute taboo topic of recent Christianity, (most people, male and female, simply do not want to believe that women have the type of sex drives that would be tempted by it), but I know it was very present within our dorms. Yet, even with all of these very real ways in which we young women were struggling with our sexuality during college, we never once stopped believing that we might not actually like sex itself. I'll never forget the time there was a panel discussion on the topic of sex at the college. I didn't attend it myself, but something was said by one of the panel members that threw all of my female friends into a tizzy worrying about whether or not they would like sex after getting married. One of my friends was engaged and I can still see the panic-stricken look on her face as she worried about what her future would hold. A few days later, a recently graduated and married friend visited campus and many of my friends fell upon her with questions about whether or not she liked sex. An open and unassuming person, she simply smiled widely with a glint in her eyes and said, "Yes. Very much. You have nothing to worry about." A loud collective sigh echoed throughout campus. Somehow, despite everything that almost every fiber of our bodies was telling us about our sexual desires, we needed convincing that it was possible for women to like sex. I never needed convincing that I would like sex, but I did need to understand that my sex drive did not make me less pure as a woman. I had many fears about sex going into marriage, but figuring out how to want sex was not one of them. It's sad to me now that I ever feared I was too sexual. How can that even be a thing? I and many of my dear friends often talked with each other about wanting to get married simply so we could have sex, but these conversations were always quiet and in private so that we would not seem like “those” type of women. It is a common idea within the Christian community that it’s good for men to get married so that they do not burn in lust, but who has ever heard women openly talk about the goodness of getting married for their own sexual needs? During the first few months of my marriage, I had a recurring experience after having sex with my husband. We would have a glorious experience, full of love and adventure, but when we finished, I would go and sit in the bathroom by myself. A few times I cried, but mostly I just sat as a certain wave of emotion rolled over me. I still can't name the emotion specifically, but there was a sense of emptiness and loneliness to it, along with a profound recognition of loss. It was similar to homesickness, but wasn't the same. I was not unhappy; I had just been exuberant. I was not ashamed; I have never been more sure and confident of my body. I was not really lonely; my husband is my best friend. The feeling stopped after a few months and the farther away from it I’ve come, the more I think it stemmed from the perceived loss of my sexual identity. Before marriage, Christian women have a certain and particular identity - sexless and pure. And now, all of the sudden, in the throws of marital passion, I was experiencing a profound and fundamental shift of identity. I was now a fully recognized sexual being in the eyes of my Christian subculture. During my times sitting in the bathroom, my soul was mourning the passage of my perceived purity. But how was I at all any less pure than before I was married? How was I any more a sexual being than before I was married? It seems to me that in our Christian views concerning sex, men simply go from being inactive sexually to active. Why is the change for women so much more fundamentally deep and dramatic? Because the Christian community tends to falsely believe that sexual purity for men is a matter keeping in check something that is already present, while for women, marriage is the turning on of a sex drive that shouldn’t have previously exist. Like men, women are sexual agents and the Christian community has got to start talking and acting like this is true. In a culture as saturated with sex as our is, we need our mothers, grandmothers, sisters, aunts, and dearest friends to be showing the younger generations that they are sexual beings who have something to say to us. Of course there are tasteful and dignified ways to do this, but there is nothing healthy about us pretending that sex is not an issue for women. Women want sex and we can either keeping telling them to deny their identities as sexual beings or we can start an ongoing conversation about the glories of female sexuality as God created it. So... let's talk about sex. ~Hannah Addendum: This post was getting really long, so I’m leaving it here for now. But this is a conversation we want to keep having at Carved to Adorn. I’m listing a few points below that I think would be beneficial for anyone to consider when taking up this topic and hopefully Ruthie and I can attempt to write about them in the coming months. First, Christian purity does not equal female sexlessness. Second, women and men may experience sex differently and prefer different aspects of it, BUT women do indeed love sex. Third, in most cases, good sex takes work, so if a woman does not enjoy it right away, it doesn’t say anything about her (or the gender as a whole’s) natural capacity to enjoy sex. The wisest and best women (and men!) know there are ways to increase your pleasure during sex. Fourth, women are not limited to liking sex when they are young, but rather they can and do love sex throughout the many different stages of life. If these points can start to be more a part of the general conversation concerning female sexuality, we will make long strides in helping women, young and old, embrace all that God made them to be. Living with members of the opposite sex - nothing new in our culture. Whether romantically linked, sexually involved, or just friends, America does not bat an eye at the practice of unmarried men and women sharing domestic living situations.

But what about the growing trend of young Christians in "platonic" co-ed living situations? The decision to do so and justifications for it baffle my parents' generation. My mom and I have recently been talking about the topic and since what used to be a no-brainer (that unmarried male and female Christians do not live with each other before marriage) now is up for debate, she asked me to share with her what I would say to a friend considering such a living arrangement. Here it goes... 1) Grey areas The first issue is that there aren't Biblical proof texts concerning such living arrangements. While scripture speaks in black and whites about adultery and lust, it doesn't say anything specific about this modern problem within the church. So in addressing it, the grayness of the issue needs to be recognized up front. My generation is always defending themselves with the grayness of a situation. So in talking about it, we have to first establish not only that there are Biblical principals connected to such living situations, but that they are relevant and important to consider. I think examples of other times in life when Christians believe something is very clearly right or wrong, not because of a direct command, but because of general Biblical principals are important. Take physical abuse. The Bible does not anywhere give us a direct command not to harm our spouses, children, friends, etc. But because the Bible clearly teaches the value and dignity of humanity and commands to treat others as we would be treated, we do not question the wrongness of abuse. It's a moral decision based not upon command, but upon principal. Could someone find loopholes? Yes, and they do. And we believe they are terribly wrong for it, holding them accountable for their actions. The problem is that living with someone is not a violent physical offense, therefore making it benign to my generation. We have been culturally conditioned to see violence as wrongdoing and anything else as personal preference. Those within the church aren't free from this conditioning. But according to scripture, more than just violent behavior is wrong and bad for us individually and as a community. So people first have to be convinced that they can commit true and real offenses simply by the situations in which they put themselves, regardless of the grayness of those situations or their seemingly passive/nonviolent nature. 2) The divide of body and soul I think the biggest problem with modern American is that we have divided our bodies from our souls (to use generic terms). It's visible everywhere, but nowhere more so than in our sexuality. We see ourselves as a conglomeration of two totally different things - a body and the whatever else is inside. These two things are forced to coexist, but have little else to do with each other. In other words, the average American sees herself as an inside and an outside. What the two do are completely separate so that we are people divorced within ourselves. This is one of the biggest arguments being used against sex before marriage - your acting one way with your body and another way with your soul, but it's awfully hard to divorce the two and if you do succeed, you're living in a fractured world. I think, though, that Christians need to hear that this problem flows both ways. In the same way that you can't divorce your soul from your body while sleeping around, you can't divorce your body from your soul while sharing living space. The totality of our beings include different elements and they are created to work in unison with each other. And that's where the issue of instantaneous significant other comes into play. People find themselves with instant significant others in many different situations, work being a good example. All of the sudden there is another person who is significant in our decisions, space, and time. These things lead to emotional connection and response. Living together goes one step further in creating instant significant others. In living together, people are creating a household. I think that this alone is reason enough not to have roommates of the opposite sex. On an emotional level alone, you are already divorcing yourself. You are putting yourself in a situation that calls for certain emotions and feelings, while at the same time neutering your heart so that those feelings don't arise. Or, if your not emotionally stunted, your heart overwhelms you and the emotions take over. Either way, your living in a situation that requires emotionally fracturing of yourself. But I think it goes one step further. Sex is a natural step in domestic relationships between men and women. It's part of life when men and women live in close and constant relationship with each other. We all know that as Christians, if we're living with someone and sleeping with them, it's sin. But we don't recognize that if we are living with someone of the opposite gender and not sleeping with them, we're not living naturally. We're splitting ourselves from what we are naturally made to do. The platonic co-ed living arrangement divorces sex from the situations in which it should naturally occur. 3) Pop culture The funny thing is that pop culture is actually agrees with this. There isn't one movie or TV show about men and women living with each other that hasn't assumed they will eventually deal with the issue of sex. In fact, it's most often the driving plot line. A man and woman start out in a platonic relationship and then wham! sex gets thrown into the mix and the big question is will they or won't they? Friends, possibly the most culturally informative and defining sitcom of the last twenty some years, is always addressing this question. Every single time living situations become co-ed, sex becomes involved. It's not cast as anything strange or unusual. It's life. Sex is the normal outcome of domestic households. 4) Lust Another thing, though, is that I don't think young Christians really take lust seriously, or even have a working definition of what lust is. The fact is, lust is so commonplace in our culture that we don't even notice it. It's the primary responses between men and women and totally and completely accepted, if not glorified. Desire and desirability are the key lens through which my generation looks at others and themselves. It is important to make sure people actually understand what lust is and what Jesus says about lust, because it is not a gray area. Additionally, though, it is really important to not separate women out from dealing with lust. It's good to talk with women about the issue as the object of male lust and helping their brothers in Christ, but it is just as important, if not more so, to talk with women about their own lust. The church tends to desexualize women, giving it nothing to say to the trends among America's young females. Women lust far more than the church recognizes and our culture is actively encouraging it. A woman's lust will most often look different than a man's, but it will be present. 4) Myth of the "relationship status" The last big thing to understand is my generations inflated view of "relationship status." Contemporary American culture is all about labeling ourselves and our male/female relationships fall especially prey to this. We want to be able to label and define every relationship we have, thereby defining ourselves. Where this connects to roommate situations is that we young Americans tend to believe that these labels actually mean something. I think young Christians going into co-ed living situations really think that because they all label themselves as single and platonic, this label will somehow magically hold true. We don't tend to understand the organic nature of relationships. Cooking dinner, doing laundry, watching TV together defines a relationship far more than whatever label might be given to it. I think it would be helpful for people to start actually thinking about the actions they do together and what they mean and produce, rather than the superficial status they've given a relationship. 5) Authority, convenience, and rebellion In the end, though, I really think a lot of the problem comes down to three things. 1) Americans don't believe in any authority in their lives. 2) Americans are controlled by what is convenient. 3) Americans are infatuated with rebelling. You can talk about the above points with someone till your blue in the face, but unless the Spirit is leading them to let go of these three big things guiding all American youth, there is no reason for them not to live together before marriage. ~Hannah  In her 2005 book, Female Chauvinist Pigs: Women and the Rise of Raunch Culture, Ariel Levy addresses what anyone with two eyes has noticed – American culture celebrates a raunchy version of female sexuality with gusto and flair. This isn’t new information to anyone. But what Levy does highlight in a new way is the more than willing participation (and even leadership) of American women in creating and developing an environment where prostitutes, strippers, and three-somes are considered the ideals of thrillingly liberated womanhood. But again, this is nothing new to anyone who turns on the television or picks up a magazine once in a while. Phenomena such as Girls Gone Wild, Paris Hilton, reality tv, and pole dancing have become so integrated with pop culture that one no longer needs to read an entire book (nonetheless a review!) about the trend to notice it. So what is this review about? What kept me reading Levy’s book and caused me to furiously underline almost every paragraph was her own response as an avowed feminist to the problem. The reader senses Levy’s natural outrage at what she investigates, particularly in her chapter concerning the effects raunch culture (female exhibitionism) has on teenage sexuality, but she cannot bring herself to give moral weight or significance to the cultural trend. Levy’s worldview does not provide her with a strong enough reason to reject what bothers her so intensely. She feels something is wrong, but has only shallow arguments with which to try and persuade a self-indulgent culture that porn stars really are not the ideal images of female liberation. Levy’s one and only argument against raunch culture is interestingly post-modern. The stereotypical post-modern argument for female liberation starts with the individual creating her own truth and happiness. Because Levy agrees, she carefully repeats throughout her book that raunch culture does not bother her in and of itself. According to Levy, what bothers her, and deeply so, is the way in which she feels all women are pressured into such trends, often by other women. In other words, Levy wants to say some women do naturally desire to be porn stars and flaunt certain kinds of sexuality, but she personally does not want to, so it should not be a cultural standard for women. Levy views sex as a mysterious thing that every person should experiment with in order to discover her personal preferences. Therefore, society should have no culturally prescribed expressions of it. The only criticism Levy makes of raunch culture is that all women are expected to participate in it as a collective standard for female sexual liberation. Female Chauvinist Pigs displays Levy’s passion concerning female sexual trends, but it is exactly that passion which weakens Levy’s actual argument against raunch culture. Almost every page of her book belies an outrage and disgust at something Levy cannot seem to fully accept even despite her stated qualifications. The book’s central argument at times seems completely lost as Levy first works to document trends and occurrences she finds outrageous and then quickly inserts her relativist objections. She repeatedly shows the unhappiness, dishonesty, and lack of sexual pleasure the women she interviews experience, and yet she is constantly stating that she is sure some woman somewhere actually enjoys such sexual exhibitionism. Additionally, she dedicates a significant portion of her text to arguing that most people, male and female, do not like the current trend. In a book where the philosophical stance is that there should be no overarching standards or sexual ideals, her arguments against the trend because “most” people do not like it does not fit. Levy waffles between her passionate dislike of raunch culture and a highly intellectual and relativistic criticism of it. But even Levy’s philosophical objections to the current trend do not deal with the real problem: the communal nature of humanity. Her argument is based solely on the individual. What the individual wants and likes, she should get. There is no consideration made for the fact that very few women, let alone people, make decisions based solely on what they want or like without any influence from peers. There is no realm of life where this is more true for a woman than in the realm of sex. Female sexuality is grounded on being delighted in and admired by the partner. When the number of sexual partners is limitless, though, so are the number sexual competitors. Life does not give women a relational vacuum in which to decide what they want and like in order to then just go out and get it. The things we learn about ourselves and the things that define us exist against the backdrop of every person, male and female, we are connected to and engage with throughout our lives. And as our world gets smaller and smaller, the number of people we interact with increases. For a woman desiring to be sexually admired and valued in a world where there are no expectations for the responsibility of doing so belonging to one person, the push towards exhibitionism is only natural. The larger the pool for competition, the more a woman must do and display to single herself out as desirable. Oddly enough, Levy adds an afterword in which she argues that the thing to combat the tide of raunch culture is a new generation of idealists. I assume she means to promote the ideal of each woman’s prerogative to define sex for herself. As I just argued, though, it does not work. Levy is right that what we need is a new idealism. But instead, I propose the old fashioned ideal of one woman and one man, for life. Women do want to be admired and delighted in sexually, but if we make sex a limitlessly individualistic endeavor, we also make it a limitlessly competitive endeavor. People do vicious things when in boundary-less competition with one another; on the other hand, rules provide safety and promote consideration within a community. I even venture to say that rules are what create community. The difference between a society of individuals competing endlessly for attention and a community living in harmonious respect for each other is often the rules and agreements by which the community lives. Concerning female expression of sexuality, the only thing that will halt the current trend will be a rise of communities committed to following shared rules for the benefit each individual. ~Hannah |

Archives

October 2018

Categories

All

|