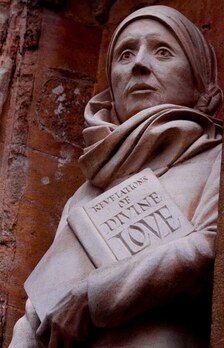

If you’re familiar with any Christian mystics at all, it’s likely you’ve heard of Julian of Norwich. She wrote extensively on the love of Christ and had a poignant understanding of God’s grace, due in part to an illness that almost claimed her life at the age of thirty. She was an anchoress, which means that she lived a large portion of her life cloistered in a small room attached to the church of St. Julian in Norwich, England, and as she aged and her notoriety spread, she gave extensive advice and guidance to the men and women who came and sat outside her cell. About two thirds of the way through reading her book Revelations of Divine Love, I came across these words: The second person of the Trinity is our Mother in nature, in making of our substance: in whom we are grounded and rooted. And he is our Mother in mercy, in taking of our sense-part [here she refers to the physical embodiment of humanity]. And thus our Mother is to us in diverse manners working: in whom our parts are kept undisparted. For in our Mother Christ we profit and increase, and in mercy he reformeth us and restoreth us, and, by virtue of his passion and his death and uprising, oneth us to our substance [here she uses “substance” to refer to our souls being reconciled to God]. Thus worketh our Mother in mercy to all his children which are to him yielding and obedient. (Ch. LVIII) There are certainly parts of Julian’s writings and theology that I disagree with. And yet as I read her thoughts concerning this metaphor of Christ as a good, wise, and loving mother, I found myself both moved and unable to find anything theologically wrong with her analogy. I know this teaching is a stretch for anyone from a protestant background. But before your guard goes up, I invite you to stay with me while we walk through this idea, and let me unpack what I believe is not only a sound metaphor, but a useful and needed one. And, of course, why we should be careful not to misuse it. Julian begins her metaphor by talking about how Christ takes on the role of a mother in his work of creation, redemption, and renewal. Athanasius, in his beautiful work On the Incarnation, draws a parallel for us between the Word that God used for creation in Genesis 1 and the Word that is referred to in John 1 by saying: “The renewal of creation has been wrought by the Self-same Word who made it in the beginning.” The Word, we understand, is none other than Jesus Christ, the second person of the Trinity. In this grand act of creation, redemption, and sustenance, Julian sees the characteristics of a mother: I understood three manners of beholding our Motherhood in God: the first is grounded in our nature’s making; the second is taking of our nature— and there beginneth the Motherhood of grace; the third is Motherhood of working [here she refers to how Christ enables us to be sanctified]— and therein is a forthspreading by the same grace, of length and breadth and height and of deepness without end. And all is one love. (Ch. LIX) It’s not difficult to see the parallels between the act of birth that an earthly mother performs and the creation of our beings by the Word (Christ). It’s also easy to see how a mother’s care and devotion to her children is similar to how Christ sustains and upholds our very beings. Julian then draws a parallel between a mother breastfeeding her children and how we feed on Christ in communion: The mother may give her child suck of her milk, but our precious mother, Jesus, he may feed us with himself, and doeth it, full courteously and full tenderly, with the blessed sacrament that is precious food of my life; and with all the sweet sacraments he sustaineth us full mercifully and graciously... The mother may lay the child tenderly to her breast, but our tender Mother, Jesus, he may homely lead us into his blessed breast, by his sweet open side, and shew therein part of the Godhead and the joys of heaven, with spiritual sureness of endless bliss. (Ch. LX) It was when Julian began to unpack even further how Christ is like a good mother to us that I felt the metaphor become truly compelling. The mother may suffer the child to fall sometimes, and to be hurt in diverse manners for its own profit, but she may never suffer that any manner of peril come to the child, for love. And though our earthly mother may suffer her child to perish, our heavenly Mother, Jesus, may not suffer us that are his children to perish: for he is all-mighty, all-wisdom, and all-love; and so is none but he— blessed may he be! He willeth then that we use the condition of a child: for when it is hurt, or adread, it runneth hastily to the mother for help, with all its might. So willeth he that we do, as a meek child saying thus: “My kind mother, my gracious mother, my dearworthy mother, have mercy on me.” And if we feel us not then eased forthwith, be we sure that he useth the condition of a wise mother. For if he see that it be more profit to us to mourn and to weep, he suffereth it, with ruth and pity, unto the best time, for love. And he willeth then that we use the property of a child, that evermore of nature trusteth to the love of the mother in weal and in woe. (Ch. LXI) To summarize: like a good earthly mother who allows her children to suffer in small ways as they grow and learn, Jesus lets us “fall sometimes;” but unlike an earthly mother who cannot be sure that no true harm will come to her child, Jesus as the true mother assures us that he will not let us perish. When we are afraid etc, we may run to Jesus and beg him for help. And when we need to scream and cry and weep, he allows us to do so as long as we need to, until we are quieted and comforted by his love. This is a beautiful and Biblical understanding of one of the aspects of Christ’s character. The image of Christ as our mother is necessary and important to us in the company of all the other metaphors of Christ that we are given. As Tim Keller stated in one of his sermons, it’s extremely important that we don’t cut out or over-emphasize any of the metaphors scripture gives us, because they are meant to work together to give us a full picture. It’s important that we understand that Christ is our brother, that he is our bridegroom, that he is our savior, that he is our creator, that he is our mother. Each of these give us an essential understanding of who he is and how we can approach him. And just as we can understand the metaphor of the bridegroom without believing that we will literally have a wedding with Christ, we can understand the metaphor of Christ as our mother without believing him to actually be a woman. The idea of Christ as a mother has been de-emphasized to the point of becoming obsolete in the protestant tradition. And yet Jesus refers to himself as a mother hen when he says: “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the one who kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to her! How often I wanted to gather your children together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings, but you were not willing!” (Matthew 23:37) There are other places in scripture that set a precedent for using feminine metaphors to refer to God. Psalm 131 says: “Surely I have calmed and quieted my soul, Like a weaned child with its mother; Like a weaned child is my soul within me.” Deuteronomy 32:18 speaks of God as a mother giving birth: “You were unmindful of the Rock that bore you; you forgot the God who gave you birth.” The book of Isaiah is rich with feminine metaphors, such as: “As a mother comforts her child, so I will comfort you; you shall be comforted in Jerusalem.” (66:13) “Can a woman forget her nursing child, or show no compassion for the child of her womb? Even these may forget, yet I will not forget you.” (49:15) “For a long time I have held my peace, I have kept myself still and restrained myself; now I will cry out like a woman in labor, I will gasp and pant.” (42:14) In the creation narrative itself, we are shown that God holds both male and female aspects within his character: “So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.” (Genesis 1:27) There is certainly a way to take all this too far. By and large, God refers to himself as male, and I believe we should do the same. And yet this is one thing I really love about Julian’s writing; she is very clear that Christ is a “he,” and yet he can also be seen as a mother. There is no reason not to use this analogy, just as we would consider it wrong to set aside the analogy of Christ as our living water or Christ as our brother. What I think often gets missed is how necessary this metaphor is. Christ has a male body; God the father most often refers to himself as male; yet it is theologically correct to say that God is neither male nor female. To look at God only through a male lens would be to negate certain aspects of his character. We are invited through scripture to understand both male and female gender in the character of God, and he provides metaphors of all kinds for us to try to comprehend this. It’s important to communicate just how essential it is for women to see their own gender reflected in the character of God. I’ll use this example: over the years, I’ve had a few different men read my books only to tell me how disorienting it is for them to read the stories, because they are forced to spend so much time trying to see and understand the world through a woman’s eyes. What I have gently tried to explain to them is that for women— particularly for women who study literature— trying to see and understand the world through the eyes of a gender not our own is our most common experience. It’s helpful and good for me to look at the world through the perspective of a man, but there comes a time when I need to rest and to be affirmed in my own experience of being female. This is something God himself provides when he gives feminine metaphors for his character; and for the church to take this away from female Christians is reprehensible. It is detrimental to men in the church as well; if God did not intend for us to understand him through both male and female analogies, he would not have included them. Just as God is without gender and holds both male and female within his character, men and women are invited to understand God through the eyes of their own gender, as well as through the eyes of the opposite gender. Whether we feel comfortable referring to Jesus as “Mother Christ,” as Julian does, there is great value in this metaphor of his wisdom, love, and mercy, and we would do well to explore it. Let’s stay away from the pendulum swing (we can see and understand the metaphor without turning away from the masculine pronouns God uses to refer to himself) but let’s also not be ruled by fear when it comes to the words of scripture. Along with Julian, we should rejoice in this maternal understanding of Christ’s goodness and love. The food of mercy that is his dearworthy blood and precious water is plenteous to make us fair and clean; the blessed wounds of our savior be open and enjoy to heal us; the sweet, gracious hands of our mother be ready and diligently around us. For he in all this working useth the office of a kind nurse that hath naught else to do but to give heed about the salvation of her child. It is his office to save us: is it his worship to do for us, and it is his will that we know it: for he willeth that we love him sweetly and trust in him meekly and mightily. And this showed he in these gracious words: I keep thee full surely. (Ch. LXI)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Currently Reading

Open and Unafraid David O. Taylor O Pioneers! Willa Cather Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|