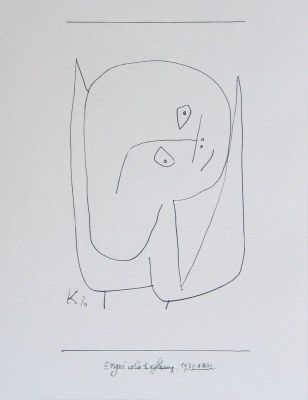

"Angel Full of Hope," by Paul Klee "Angel Full of Hope," by Paul Klee A few months ago my sister-in-law Bethany suggested we read “The Color of Compromise,” by Jemar Tisby. It’s a book that recounts the history of the American church’s complicity in racism, using examples from each era of the United States’ history, from the arrival of Europeans to the present day. It is thorough, concise, and wrenching. As I’ve read it, the weight of it has been immense. I am aware that my experience with it is only a fraction of the pain that my brothers and sisters of color feel, and yet there is something uniquely painful in being one of the perpetrators. There is no place for me to hide; no one else to blame. There’s nothing in the book that has surprised me, but it’s gone a long way toward helping me contextualize the corporate nature of racism in America. Christians are a people who have a long history of accepting a corporate identity, throughout the Bible and throughout church history, and yet the extent to which the American church has taken refuge in the idea of an individual identity runs deep. To understand where we are today, one has to acknowledge that racism is a corporate sin. White Americans have unwittingly (and often wittingly) benefited from the fruits of racial inequity throughout the history of the United States, and that burden is on our shoulders. Last week I thought to myself, “We could apologize forever to black people and still it would not be enough.” Though I know that statement is difficult for many of my white brothers and sisters to acknowledge, it brought an intense sense of freedom to me, because what I have finally realized is the deep connection between my Christian faith and my understanding of how to process race relations. The key to both is a true comprehension of sin and grace. None of what I say will make sense without a real, and not just intellectual, understanding of sin. The difference between cultural Christianity and a life-altering faith is just that: a sense of one’s own sin. Jesus’ blood means nothing to a person until she has explored the reaches of her own wickedness: until she has stared at herself in a mirror and been honest about what she sees. Until she can say with surety, “There is no difference between me and the murderer, the rapist, the genocidist. There is no difference between me and the slave-owner.” This is hard. And yet this is the gospel. We believe that man is held accountable for the sins he commits, and God will judge the rapist more harshly than the man who has only contemplated it in his mind. But the crux of the gospel is understanding that the ability and the desire to perpetrate any of these acts is written on all of our hearts, and we therefore have no cause to elevate ourselves higher than anyone else. When this reality breaks through, the only thing one can do is weep and beg for mercy. The glory of the gospel is that mercy is, in fact, given. We are restored. That is why dedicating one’s life to Christ seems so small in comparison--so obvious. The wild riches of the mercy lavished on each one of us, when we honestly see the darkness of our hearts, is enough to break us with its glorious joy, and forever stop us from judging our fellow humans. This, the heart of the gospel, is incomprehensible to many people who have been told that humanity is mostly good; who have been trained since childhood to believe in themselves. It’s wildly countercultural. And yet we’re seeing people grapple with it in ways they haven’t before. The question of forgiveness is of utmost importance right now. Can a man who has been “me too-ed” be forgiven? Can someone who posted photos of themself in blackface attest that they’ve changed? Do people change? The push to see everyone in stark contrast--either right or wrong--is startling. None of us has a clean slate--none of us has lived a life in which we never said or did anything offensive. But now the cliff looms large. Once you fall off, there is no return. For a long time now, I’ve been considering what the impact of grace would mean for our culture. At our core, so many of us are absolutely terrified that we will be found out--that someone will identify something we’ve done as being on the wrong side of history, and then we will be cast out. What is most precious to us--our good name--will be ripped from us and we will have nothing. And because our image is so tied to our careers and our incomes, there is a very real possibility that a fall from grace would not just mean emotional ruin, but physical and financial ruin too. In some cases this has led to false apology: a quick rush to say the right things without really comprehending the depth of the evil we are asking black friends to forgive. What would it mean, then, to live in a world in which far from being terrified of being found out, we were free instead to shout YES! I have failed. I have hurt people. I have destroyed and sinned. But instead of being ruined and shunned, I am forgiven. I am more free now than I ever was, back when I thought I was good. It would transform our communities. It would transform our churches. It would transform race relations. I am not afraid to admit that I could apologize forever to my black brothers and sisters and still never atone for my personal and corporate sins because I know that I could apologize forever to God and still never atone for my own sin. To be clear, when I talk about forgiveness and grace I’m not necessarily talking about the act of black Christians forgiving white Christians. That is a complicated subject, and I am not the best voice to address it. What I’m talking about is the initial step in the process of repentance: the assurance that God has and will forgive us when we truly repent, and the way that grace frees us to live in continual humility, without fear of what mankind might say about us. We do not fear condemnation, and we do not fear man. There is no room in this world of grace, white brothers and sisters, for self-righteousness, pride, or fear. What our black siblings in Christ--and the many non-believers we are charged to bear witness to--need from us is not denial or a false groveling designed to make us feel better about ourselves, but rather an honest, clear eyed understanding of how much we have sinned and how much we have been forgiven. Just as we cannot move forward into life with Christ without recognizing the depth of our ruin, we cannot move forward as a nation without recognizing the deepness of the systems we’ve put in place at the cost of the blood of our black countrymen and women, and we should not fear to acknowledge it. We are all defensive--those who would prefer to keep sweeping injustice under the rug, and those who, racked with fear of man, have made a show of their apologies. To the former I say: take an honest look. Research the history of our country. Start with “The Color of Compromise,” and let it grieve you to your core. Be weighed down, so that you can rejoice in the joy of restoration. And to the latter I say: be free. Do not fear what man can say or do, but understand the depth of your own sin so that you are not so quick to judge. Rejoice not just in the right things you’ve said, but in the mercy and grace given even to you--to me--to us all. We are the worst of sinners, all of us. And we have been restored. Let us go forward without fear, in humility, and like the Israelites in the Old Testament, let us allow the repentance of our hearts to lead to the tangible transformation of our homes, our places of worship, and our cities.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Currently Reading

Open and Unafraid David O. Taylor O Pioneers! Willa Cather Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|