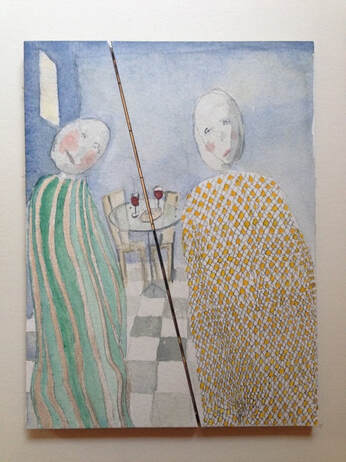

Recently I’ve been thinking about disagreeing with people: the way I approach it, the way I talk about it, the way I talk with and about those who disagree with me--all topics I encounter every day. Mostly, I’ve been thinking through how to disagree with other Christians, and that’s what I want to spend most of my time discussing here. To begin that discussion, I need to start a little further back, and talk about the difference in how believers are called to treat those inside the church in comparison with those outside the church. Until I moved to New York City in my mid twenties, I didn’t have an understanding of the distinction between how to treat those who profess the beliefs of the Bible, and those who don’t. I spent a lot of time as a teenager feeling angst about how I wasn’t calling my unbelieving friends out on the choices they made, and feeling a nagging guilt that I was somehow responsible for their morality. It was a hugely clarifying (and humbling) realization, therefore, to come to the place of distinguishing between my attitude toward believers and my attitude toward non-believers. An enormous amount of the New Testament is devoted to counseling and discipling those within the church and instructing believers how to treat one another. It’s important to note that these instructions are given specifically to those within the body of believers. This doesn’t mean the church has nothing to say to an unbelieving world--far from it. As Christ instructed in Matthew 28:19-20: “Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you.” In matters of harm to others (such as stopping the wrongful taking of life, or passing laws to prohibit abuse and extortion) there are clear commands for believers to intervene in culture. What I missed as a teenager is this: the starting place for believers is not telling someone who doesn’t hold the beliefs of the Bible that they’re violating the commands held within it, because those commands mean nothing to someone who doesn’t believe in the God who put them in place. The great commission is a call to “make disciples” by sharing the good news of the gospel, modeling a Christ-like love, and being orderly and charitable to other believers within the church. We can’t put the cart before the horse--as the church so often has--and call people to repent of their sins before the Spirit has revealed himself and convicted them of his presence and their own need for the words of scripture. This was a revelation to me in my mid-twenties, and it’s completely reoriented my relationships with people outside the church. By removing myself from the seat of judgement, I am actually freed to live more fully as a believer and to joyfully proclaim the invitation of God’s grace, trusting that he will continue the work he is doing in the hearts of those around me. And yet the longer I am in leadership in the church, the more I see why the long letters in the New Testament to believers are necessary, for we in the church do not know how to disagree. The first step, of course, is agreeing that it’s okay to disagree. During my undergrad, I remember a fellow student telling me that he felt all believers should join the Roman Catholic Church even if they held severely different beliefs, because according to him the most important aspect of belonging to the church was unity. (For the record, he did not hold to many Catholic beliefs himself.) I understand this view, and I get where he was coming from, especially with the legacy of so many non-denominational churches in the US that are sort of lone-rangers, totally divorced from much of the historical church and creeds. But his argument also sort of feels like the argument for complete cultural homogenization, which is essentially negating the experiences and cultures of minorities. The church is stronger when it allows for theological diversity among its many members, especially now that more women and more cultures outside the West are coming to the table (such as the burgeoning church in China or the vibrant Anglican, Baptist, Pentecostal etc churches across South Africa, Nigeria, and many other nations.) Opening the door to disagreement, however, is inarguably scary. We believe that the Bible holds life within its pages, and Christians are rightly concerned about taking its words and their own interpretation seriously. As a Presbyterian, it should come as no surprise to anyone that I believe theology truly matters--whether it’s in the way I understand my own personal life and problems, or the way the church at large operates. It matters a lot. With this in mind, I believe there are three helpful ways of viewing conflict that have the ability to transform the way the church deals with disagreement: first, a correct understanding of first and second order issues, second, a true sense of personal humility and respect for other believers, and lastly, a real understanding of God’s sovereignty. Understanding first and second order issues. When I lived in New York I attended an Evangelical Presbyterian Church (EPC), and though I’ve since gone back to the Prebsyterian Church in America, I gained a lot of respect for the EPC because I feel that they have a great understanding of how to agree on certain issues, and disagree on others. Their denomination is built on the concept of first and second order issues, which is this: there are some things that Christians must believe in order to be Christians (first order issues) and there are some things that it’s okay for believers to have a breadth of opinions on (second order issues). By placing some things in the category of second (or third, or fourth) order, Christians are essentially saying that as long as those first order beliefs are aligned, they can work with and fellowship with other Christians as co-laborers in the service of Christ. First order beliefs are typically doctrines such as the inerrancy of the Bible, belief in the Trinity, belief in the physical death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, etc. Second order beliefs can be anything from the gender of elders to the age of the earth to infant vs. adult baptism. Second order issues can be very important, and yet we must be able to have disagreements in these areas and still have respect for those we don’t agree with. An often quoted example of this in the early church is found in 1 Corinthians 8, where Paul discusses whether it’s okay to eat food sacrificed to idols. He essentially says that some will make the choice to eat it, and some will not: “But food does not bring us near to God; we are no worse if we do not eat, and no better if we do.” (v. 8) Later in the same letter, Paul goes on to make the argument of first (and therefore second) order issues by writing: “For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures.” (1 Corinthians 15:3-4) Believers will disagree about the interpretation and application of scripture; it’s a part of our limited comprehension and wisdom as humans. How we disagree, and how willing we are to work with those we disagree with, is the important thing. This is all the more applicable with the recent celebration of Pentecost just this past Sunday. So much of language has the nuance of culture tied into it, and to quote my brother Daniel: “Language is more than information transfer, and the Holy Spirit speaks in all tongues. Theology of second issues is often challenging because the hermeneutics of our own interpretation is difficult to transfer culturally. In light of Pentecost, we are called to humility.” Respect for those we disagree with. This brings me to perhaps the most challenging point, and one that has been personally humbling for me in recent months. One common failing of Christians in my tradition (which places a lot of emphasis on understanding) is hubris associated with believing that we have all the right doctrines. I don’t mean to say that there’s anything wrong with spending time studying and interpreting scripture, and I don’t mean to say that believers should not seek to know what scripture is saying. Still, I have been convicted recently of my own limits of knowledge and understanding. In this respect I have been truly blessed by traditions that uphold and cherish the mystery of God, such as the Anglican church. I am thankful to be able to say that there are some things I may never have a satisfactory answer to, and the longer I am a Christian the more I understand that believing I can have a firm comprehension of every topic in the Bible is actually making God far too small. (Anyone who tells me they fully understand the doctrine of predestination, one way or another, either has a much too high opinion of themselves or hasn’t truly studied the words of scripture.) I am eager and excited to continue reading and interpreting the Bible for the rest of my life, and I am sure that my understanding of it will develop as time goes on. I have opinions about what I think scripture says on many issues. But to have a robust sense of the church and a true sense of self, I must admit that I can be (and often am) wrong in my own interpretation. I believe what I believe is right--otherwise I wouldn’t believe it--but I am also willing to admit that I may get to the end of my life and find out that I had interpreted a whole host of second order issues incorrectly. This doesn’t change my convictions now, but it certainly changes how I treat other believers. Each Christian looks to scripture and interprets it, and I am called to the humility of admitting that my interpretation may not be the correct one. Rather than locking down a set of beliefs and defending them until I die, I trust that the Spirit in me and my unshakable union with Christ will lead me through innumerable relationships with believers who disagree with me, and from whom I can learn and perhaps change. A beautiful example of this in action is the relationship of George Whitfield and John Wesley, two theologians and pastors who had severe differences in their beliefs. At times their disagreements led them to open conflict and to actively work against the other. Yet toward the end of their lives one of Whitfield’s followers asked him: “We won’t see John Wesley in heaven, will we?” To which Whitfield replied “Yes, you’re right, we won’t see him in heaven. He will be so close to the throne of God and we will be so far away, that we won’t be able to see him.” Whitfield requested that Wesley, who outlived him, give the eulogy at his funeral, and Wesley is recorded as saying: “There are many doctrines of a less essential nature with regard to which even the most sincere children of God…are and have been divided for many ages. In these we may think and let think; we may ‘agree to disagree.’” Assurance of the sovereignty of God. My final thought is one of great hope, because the Bible is not a story about us--it is a story about God and his glory. When I look around in fear--when I see the church today looking around in fear--I am called back to the many, many stories in the Bible in which God was faithful to his people and faithful to his own glory by upholding his church through the ages. He stayed with Abraham in Ur, he led his people across the Red Sea and the Jordan River, he brought them back from exile, he spoke to them through the prophets, and he came himself in the flesh to be present with us and to die for us. He expanded his church through persecution, he was faithful to the missionaries who went into Europe, he stayed with his people through heresies that threatened them. The church has expanded over the world, it has done true harm and true good, and today it is rich with a diversity of cultures, peoples, and beliefs. Whatever we can envision for the church through our tiny edge of understanding, it is far less beautiful than what God himself--who uses the church for his glory and his glory alone--envisions for it. He will always sustain a remnant of people who teach the truth, and the truth will never pass away. With this in mind, we have to approach our own disagreements with the humility they deserve. There is certainly a time to stand up for what we believe the Bible is saying, and a time to confront the church when she preaches heresy on first order issues. But God has not and will never stop being faithful to his people. If he can use me, he can certainly use the believers I disagree with. My prayer is that I will believe what I believe with conviction, trusting the Spirit who enables me to understand the word of God, while maintaining a posture of humility and grace toward my brothers and sisters who interpret the Bible differently. Artwork: "The Chasm of Otherness," by Bruce Buescher

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Currently Reading

Open and Unafraid David O. Taylor O Pioneers! Willa Cather Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|