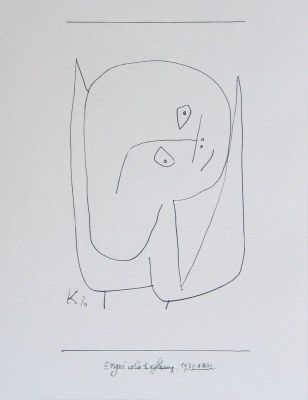

"Angel Full of Hope," by Paul Klee "Angel Full of Hope," by Paul Klee A few months ago my sister-in-law Bethany suggested we read “The Color of Compromise,” by Jemar Tisby. It’s a book that recounts the history of the American church’s complicity in racism, using examples from each era of the United States’ history, from the arrival of Europeans to the present day. It is thorough, concise, and wrenching. As I’ve read it, the weight of it has been immense. I am aware that my experience with it is only a fraction of the pain that my brothers and sisters of color feel, and yet there is something uniquely painful in being one of the perpetrators. There is no place for me to hide; no one else to blame. There’s nothing in the book that has surprised me, but it’s gone a long way toward helping me contextualize the corporate nature of racism in America. Christians are a people who have a long history of accepting a corporate identity, throughout the Bible and throughout church history, and yet the extent to which the American church has taken refuge in the idea of an individual identity runs deep. To understand where we are today, one has to acknowledge that racism is a corporate sin. White Americans have unwittingly (and often wittingly) benefited from the fruits of racial inequity throughout the history of the United States, and that burden is on our shoulders. Last week I thought to myself, “We could apologize forever to black people and still it would not be enough.” Though I know that statement is difficult for many of my white brothers and sisters to acknowledge, it brought an intense sense of freedom to me, because what I have finally realized is the deep connection between my Christian faith and my understanding of how to process race relations. The key to both is a true comprehension of sin and grace. None of what I say will make sense without a real, and not just intellectual, understanding of sin. The difference between cultural Christianity and a life-altering faith is just that: a sense of one’s own sin. Jesus’ blood means nothing to a person until she has explored the reaches of her own wickedness: until she has stared at herself in a mirror and been honest about what she sees. Until she can say with surety, “There is no difference between me and the murderer, the rapist, the genocidist. There is no difference between me and the slave-owner.” This is hard. And yet this is the gospel. We believe that man is held accountable for the sins he commits, and God will judge the rapist more harshly than the man who has only contemplated it in his mind. But the crux of the gospel is understanding that the ability and the desire to perpetrate any of these acts is written on all of our hearts, and we therefore have no cause to elevate ourselves higher than anyone else. When this reality breaks through, the only thing one can do is weep and beg for mercy. The glory of the gospel is that mercy is, in fact, given. We are restored. That is why dedicating one’s life to Christ seems so small in comparison--so obvious. The wild riches of the mercy lavished on each one of us, when we honestly see the darkness of our hearts, is enough to break us with its glorious joy, and forever stop us from judging our fellow humans. This, the heart of the gospel, is incomprehensible to many people who have been told that humanity is mostly good; who have been trained since childhood to believe in themselves. It’s wildly countercultural. And yet we’re seeing people grapple with it in ways they haven’t before. The question of forgiveness is of utmost importance right now. Can a man who has been “me too-ed” be forgiven? Can someone who posted photos of themself in blackface attest that they’ve changed? Do people change? The push to see everyone in stark contrast--either right or wrong--is startling. None of us has a clean slate--none of us has lived a life in which we never said or did anything offensive. But now the cliff looms large. Once you fall off, there is no return. For a long time now, I’ve been considering what the impact of grace would mean for our culture. At our core, so many of us are absolutely terrified that we will be found out--that someone will identify something we’ve done as being on the wrong side of history, and then we will be cast out. What is most precious to us--our good name--will be ripped from us and we will have nothing. And because our image is so tied to our careers and our incomes, there is a very real possibility that a fall from grace would not just mean emotional ruin, but physical and financial ruin too. In some cases this has led to false apology: a quick rush to say the right things without really comprehending the depth of the evil we are asking black friends to forgive. What would it mean, then, to live in a world in which far from being terrified of being found out, we were free instead to shout YES! I have failed. I have hurt people. I have destroyed and sinned. But instead of being ruined and shunned, I am forgiven. I am more free now than I ever was, back when I thought I was good. It would transform our communities. It would transform our churches. It would transform race relations. I am not afraid to admit that I could apologize forever to my black brothers and sisters and still never atone for my personal and corporate sins because I know that I could apologize forever to God and still never atone for my own sin. To be clear, when I talk about forgiveness and grace I’m not necessarily talking about the act of black Christians forgiving white Christians. That is a complicated subject, and I am not the best voice to address it. What I’m talking about is the initial step in the process of repentance: the assurance that God has and will forgive us when we truly repent, and the way that grace frees us to live in continual humility, without fear of what mankind might say about us. We do not fear condemnation, and we do not fear man. There is no room in this world of grace, white brothers and sisters, for self-righteousness, pride, or fear. What our black siblings in Christ--and the many non-believers we are charged to bear witness to--need from us is not denial or a false groveling designed to make us feel better about ourselves, but rather an honest, clear eyed understanding of how much we have sinned and how much we have been forgiven. Just as we cannot move forward into life with Christ without recognizing the depth of our ruin, we cannot move forward as a nation without recognizing the deepness of the systems we’ve put in place at the cost of the blood of our black countrymen and women, and we should not fear to acknowledge it. We are all defensive--those who would prefer to keep sweeping injustice under the rug, and those who, racked with fear of man, have made a show of their apologies. To the former I say: take an honest look. Research the history of our country. Start with “The Color of Compromise,” and let it grieve you to your core. Be weighed down, so that you can rejoice in the joy of restoration. And to the latter I say: be free. Do not fear what man can say or do, but understand the depth of your own sin so that you are not so quick to judge. Rejoice not just in the right things you’ve said, but in the mercy and grace given even to you--to me--to us all. We are the worst of sinners, all of us. And we have been restored. Let us go forward without fear, in humility, and like the Israelites in the Old Testament, let us allow the repentance of our hearts to lead to the tangible transformation of our homes, our places of worship, and our cities.

0 Comments

King David Plays the Harp, by Dutch artist Gerard van Honthorst. I’ve written before about how, in my most recent read-through of the Old Testament, I’ve been struggling with the character of David. As I’ve read about his many sins, David has come to represent a larger issue for me, and I’ve been rebelling against the idea that David--the murderer, the sexual predator, and the ineffective father--is labeled (by scripture, and even more frequently by the church) as a “man after God’s own heart.”

The story of David, like all stories of people in the Bible, is meant to point us to the character of God, who graciously remains faithful despite the many times we fail. He is called a man after God’s own heart because he is continually penitent, continually convicted of his sin, and always crying out to God. And I can appreciate that. Yet as I’ve slogged through the book of Psalms, the words that are often so quick to touch the hearts of believers have felt like a burden to me. The many, many times that David asks God to vanquish his foes and rescue him from his enemy’s traps make me feel like rolling my eyes; all I can think about are David’s own sins. But today I read Psalm 144. It’s a beautiful passage that has within it the famous lines: “Lord, what are human beings that you care for them, mere mortals that you think of them? They are like a breath; their days are like a fleeting shadow (verses 3-4.)” But my eyes stopped on the following words in verse 12, which David inserts into a section in which he longs for the day God will fulfill his promises: May our sons in their youth be like plants full grown, our daughters like corner pillars cut for the structure of a palace (ESV) I have been thinking about these lines all day, and I can’t get over them. David--the man who took Abigail, Michal, and Bathsheba from their husbands, who did nothing when one of his sons raped one of his own daughters--this man wrote those lines. They have been sitting on my heart all day, revealing to me the anger I’ve harbored towards men who have hurt women. And I think these words are showing me a way forward. Before I get into all that, I want to take a moment to unpack the metaphors themselves. Here are a few other translations: That our sons may be as plants grown up in their youth; that our daughters may be as corner stones, polished after the similitude of a palace (KJV) Then our sons in their youth will be like well-nurtured plants, and our daughters will be like pillars carved to adorn a palace (NIV) It probably will not escape your notice that these are the very verses the name for this website was taken from. It’s been years since I reflected on Psalm 144, and even when Hannah posted this excellent piece about why we named this site “Carved to Adorn,” I don’t think I ever really considered David’s words about sons, focused as I was on his metaphor for daughters. But what are his images implying? Let’s start with the daughters. They are likened to “corner pillars,” or “corner stones,” indicating great strength and the essential nature of their character and presence. There is a mention of carving, cutting, or polishing, which implies that they have been shaped, perhaps through difficult means. And they are said to be there for the purpose of adorning or upholding a palace, which implies that they have a communal duty, since a pillar cannot hold up a structure in isolation. And the sons? They are likened to “well-nurtured” plants, and David makes a point of saying the word “grown.” The contrast between the images of a pillar and a plant was what struck me first, and what struck me next was the total reversal of who I would have expected him to attribute each metaphor to. A fully grown plant implies strength, but also fruitfulness and nourishment and new life, attributes we often associate with women. The concept of having “grown” implies suppleness, bringing to mind green and fragrant images. All of these are archetypes we tend to give to women, but here the woman is given the role of the corner pillar--strong and unmoving, dedicated in her duty--and the man is given the task of growth and new life. The more I think about these ideas, the more I begin to feel something come loose in my gut. With his words, David has cut my anger out from under me, because he has presented an idea of the flourishing of men and women that is so beautiful, it hurts. I’ve written before about how the Bible is continually reminding me that sex-discrimination is not found within its pages, although it can be found in the history of the church, and Psalm 144 is another place where I am gently being told to let go of my anger and rest in the goodness of God’s restoration. There is no place for my lingering resentment against men who have repented of their sin; to deny them my good will in Christ Jesus is to say that my sins are not as heinous as their own, and I know that is not true. Thinking about David writing these words makes me want to weep. Many think that he wrote this psalm after the defeat of Absalom--after his son dethroned him and then was killed when David was restored to the throne. Most of David’s sons were the opposite of “well-nurtured plants;” they were unrepentant rapists and murderers and traitors. The only one of David’s daughters that we are given a full story about is Tamar, who was sexually assaulted and lived the rest of her life as a “desolate woman;” she is the opposite of a strong and proud pillar. David knew what it was to see his sons and daughters in turmoil and anguish; he knew that it was partially his own fault. He made no secret of his repentance. But there is an additional layer to David’s words, because by couching the metaphor in the terms of daughters and sons, it’s clear that he was thinking about restoration. He knew that he too was a murderer and a predator (ask Bathsheba) but he believed in a God who was able to take his abused daughter and make her a pillar--a God who was able to take himself and his sons and wash away their horrible deeds as they sprouted new growth. There at the end of his life, David painted a beautiful picture of how men and women should be, and the metaphor of men like growing plants is strikingly helpful in our world: a world where women are finally taking a stand and speaking up about how they have been abused. My long journey with David feels representative, to me, of the space women have a right to; forgiveness is a journey, and sometimes a very lengthy one. Yet it is an exquisite idea to think of men bearing fruit, of growing tall and providing shade and protection for those who shelter under them. This is an idea we must pay attention to--particularly the idea of growth. In a world that suddenly seems to see people as very good or very evil, David’s metaphor holds within it the space for repentance and forgiveness, and new life. It can feel wrong to extend forgiveness--as if we’re letting people off too easily for sins they should rightfully be punished for. But it only feels too easy if we don’t understand how much we ourselves must be forgiven for; when the depth of our own sin reaches us, the grace that breaks through suddenly becomes enough to cover us all. I am thankful to say that I have never been abused, but there is a man in my past who was hurtful to me and who hurt other women I know. Over the course of many years I have seen him change; seen him grow into a well-nurtured plant. Yet though I can say with surety that this man truly has changed, my heart has held out, wanting to deny him any trust, any chance to come back into my life even in the smallest way. Through Psalm 144 God has convicted me of the anger I’ve been harboring against him and against the faceless men who have hurt other women. There is certainly a place for righteous indignation over the injustice in the world. But it is God who promises to bring judgment, and he will uphold his promise. Judgment is his, and that is very hard and very freeing to say. It is important to be discerning and protect my sisters, surely, but as a member of the body of Christ it is also essential to watch my brothers grow and repent, to recognize the grief of my own sins as well as theirs, and to welcome the fruit and shade that they provide. Whether it is towards David or any other repentant man, I am seeking not to harbor anger any longer. Instead, I am going to rejoice in our mutual restoration in Christ. A year and a half ago, I embarked on a project of reading all the way through the Bible. I didn’t make plans to do it in one year or even two years, but decided to go about it at my own pace. I don’t read every day, and I don’t read the same amount of chapters. I read however much I feel like reading--sometimes it’s a lot, sometimes it’s very little. Right now I’m in the book of Psalms.

There’s certainly a place for discipline when it comes to reading scripture--after all, there are plenty of places in the Bible itself that exhort believers to study and read it. But I don’t need to convince anyone of the guilt the average Christian feels when they admit they don’t have a daily “quiet time.” Christians know they need to read their Bibles. And that’s exactly what I want to say. I want to shout from the mountaintops: “Read your Bible!” But I also want to shout: “Read it without guilt!” Psalm 1 speaks of delighting in the law of the Lord, of meditating on it day and night, of being like a tree planted by streams of water, a metaphor that speaks to bounty and glorious satisfaction, not guilt. And for the first time in my life, I feel like I am experiencing a taste of that delight--of truly desiring to spend time in God’s word. Admitting that is humbling. There have certainly been periods of my life when I clung to God’s word, when it was sweet to me and necessary; but these periods were accompanied by trouble or pain of some kind. I have a good knowledge of scripture--I’ve read every book in it multiple times--and I have a thorough education in theology, for which I’m grateful. And my heart has wanted to delight in scripture, because I love the Lord. But until the past few years, reading the Bible was always something I did because I knew I should, not something I did because I truly, truly wanted to. The change for me came when I decided to approach it like a story. Instead of asking myself to journal or even reflect in a structured way on what I read, I simply read. I read as much or as little as I want, and the result has been transformative. I have begun to see the Bible as the story of God--not the story of how God’s plan affects me. And with this shift in perspective, it is endlessly more dear to me and much more fascinating. Understanding the Bible as the story of God, and not of me, has altered everything about how I view myself in relation to him. It’s changed me theologically as well as practically (some of which I unpacked in this previous post.) Discovering how compelling the character of God is in scripture has set me off on a new journey of reading theology, because it has reinforced to me how little I know of God, and how much help I need in interpreting his character. Reading the Bible in this way has also upended what I thought the Bible said about women, which in turn has upended how I think about myself and about the church. There is so much noise around the issue of women in the church: centuries of culturally motivated mistreatment, a pendulum swing in the opposite direction and an assumption that the Bible itself is anti-women, and so many opinions and personal experiences one way or the other. Part of reading the Bible with no agenda meant shutting out all that noise and just discovering what the story actually said. What I found was a profound understanding of what it means to be a woman, and to be honest, I was not ready for it. Far from many people’s assumption that there are no stories about women in scripture (or at least very few) I found the story that the Bible tells about men and women and the world at large to be searingly honest. There are stories of women triumphing, (like Jael and Esther), there are stories of women who are smarter than their husbands (like Abigail), there are stories of women being uplifted (like Hannah and Mary), there are stories of women who are evil (like Jezebel), and there are many, many stories of women being abused or mistreated. The fact that there are so many stories about women being abused in the Bible used to bother me, because like most people, I want heroes to look up to, not a continual reminder of how women have been treated. But as I read through the Old Testament without layering on my own preconceptions, I found something true emerging: the Bible honors women by being honest. The message of the Bible is that sin has entered the world and has wrecked it; for women, this means continually being subjugated by men. The fact that the Bible does not hide this is a testament to how women are given equal status within its pages. These are just examples of the way scripture has revealed itself to me. There is a quote attributed to Gregory the Great that reads: “Scripture is like a river...broad and deep, shallow enough here for the lamb to go wading, but deep enough there for the elephant to swim.” I find this idea comforting and sustaining, and a reminder that in our world of immediate gratification, this is one thing I can’t have instantly. There are things spoken in scripture that I don’t understand that I will wrestle with for years, if not for the rest of my life. There are bits that have revealed themselves to me only after years of mulling them over. There are things I didn’t even know I didn’t understand, only to have them change shape suddenly before my mind’s eye and become gloriously bright. What I do know, however, is that the Bible is neither a book about me, nor intended as a weight of guilt; it is a gift. What I want to say is: read your Bible. But perhaps consider reading it differently--maybe let go of your structure, and allow yourself to enjoy it as the story it is. It may change everything. Artwork by Bruce Buescher The body that is corrupted presses down the soul. The earthly tabernacle weighs down the mind that muses upon many things. - Augustine, Confessions I was re-reading Confessions when I came across the above quote. I don’t understand why people speak as if the mind is pure and the body is corrupt. To be sure, in Galatians 5 the Apostle Paul sets up the flesh (meaning the desires of the world, not our physical bodies) against the spirit (meaning the life aligned with God’s word, not our ethereal souls). And yet despite the age-old and ever-popular heresy of gnosticism (just as prevalent now as during Augustine’s time or the time of the Greeks,) the Bible is clear about the fact that we are both body and mind, and neither is more corrupt or holy than the other.

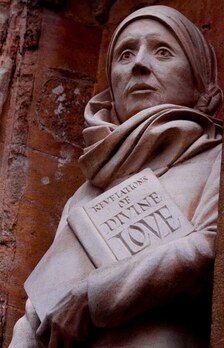

Far from understanding my spirit as pure and my body as corrupt, it always seems to be through my body, and not my soul, that grace shines most clearly, and I am grateful for the ways this has manifested over the years. It was my body that taught me, as a senior in college, that standing in a room and breathing back to back with another human being can heal. That looking into the eyes of a man doesn’t have to be sexual, that holding hands can simply be a symbol of common humanity. That having a safe way to touch someone not only brings connection but also elevation of my own person as well as theirs. I can say something to myself in my mind over and over, but if instead I learn it through my fingers and my hands, it will go straight to my core and become a part of who I am, instead of who I want to be. It is not my body that compares itself to others, but rather my spirit. While my mind reaches for any opportunity to praise or condemn my own skin--and the skins of those around me--my body moves on, digesting, stretching, sleeping, enjoying, hurting, resting. My thighs are pleased to be mine, though I am not pleased with them. My toes and ankles do their jobs, even when I reject them. My chin doesn’t care if it looks fat in photos; it wants to laugh all the same. It is my body that calms me, when my mind is racing or my spirits depressed. My legs that carry me on long walks when energy builds up in my soul, propelling me to leave, and those same legs always bring me back. It is my eyes that fill with sight, trying to remind my thoughts that what is tangible and what I feel are not the same thing. It’s my breath that calms me when I lie awake in the night, anxiety thrumming through my veins, panic seeping around the edges of my mind. In and out, in and out. The breath, at least, is constant and dependable. It does not waver. It is my mind that distrusts my body, as time goes forward and my bones and skin change; my mind that seeks to find something wrong, something corrupted, something to fixate on in worry, and my body that steadily hums; healing, thriving, slowly decaying. It’s through my body that I have learned most poignantly how fearful I am, how little I can control the world around me, how to be present in the moment I exist in. To blame the body for the corruption of the soul is like a human blaming a beloved dog for her own sin; it is the flesh that carries on and performs its duties faithfully while the spirit rails against the state of everything it touches. It is my body that forgives, touching my husband’s face, when my mind resists, and my fingers that remind me of love when my spirit stubbornly holds up the platter of wrongs that have been done to me. It’s my breath that sidles up to the platter and knocks it askew, tipping it so that the wrongs come crashing off, one by one, and once more our bodies can be quiet, unweighted and unburdened. Finally: the spirit silent, our flesh alone and at peace. It is the body that has shown me, in a darkened theater or a crowded circus tent, that some things can only be communicated through the physical--there are truths that rise up from the depths of who God made us to be, and words can’t cover or touch them. Some things live so deep, run so far below the surface, that the only way to understand them is to see and feel them physically recreated; sacred, soft, steady, and dense. It was the body, of course, that Christ required to bring redemption and healing; not the body that he suffered, but the body that he gladly took and fully became. The physical presence that God had pointed to from the very beginning, blood and lambs and sacrifice because it’s who we are, not something to seek to avoid. He took a body not just so that we could be elevated, but because the physical is part of the very fabric of existence; when our bodies die we will not cease to be material, we will become even more fully embodied and truly enfleshed for the first time. These breaking bodies that are so faithful, that enforce our limits and our reality, that serve as the scapegoats of our mind’s desires--these bodies point constantly to our need for restoration and our union in blood with the body of Christ our God whose healing power rippled across not just the intangible idea of salvation we carry in our minds, but through the very tendons and muscles of our bodies. That is why we eat real bread and drink real wine as an act of communion; it’s through the physical mechanics of chewing and swallowing that God meets us and sustains us. She is faithful, this body of mine; she is far more faithful to me than I am to her. She is me, and I am honored to be her. Artwork by Bruce Buescher  If you’re familiar with any Christian mystics at all, it’s likely you’ve heard of Julian of Norwich. She wrote extensively on the love of Christ and had a poignant understanding of God’s grace, due in part to an illness that almost claimed her life at the age of thirty. She was an anchoress, which means that she lived a large portion of her life cloistered in a small room attached to the church of St. Julian in Norwich, England, and as she aged and her notoriety spread, she gave extensive advice and guidance to the men and women who came and sat outside her cell. About two thirds of the way through reading her book Revelations of Divine Love, I came across these words: The second person of the Trinity is our Mother in nature, in making of our substance: in whom we are grounded and rooted. And he is our Mother in mercy, in taking of our sense-part [here she refers to the physical embodiment of humanity]. And thus our Mother is to us in diverse manners working: in whom our parts are kept undisparted. For in our Mother Christ we profit and increase, and in mercy he reformeth us and restoreth us, and, by virtue of his passion and his death and uprising, oneth us to our substance [here she uses “substance” to refer to our souls being reconciled to God]. Thus worketh our Mother in mercy to all his children which are to him yielding and obedient. (Ch. LVIII) There are certainly parts of Julian’s writings and theology that I disagree with. And yet as I read her thoughts concerning this metaphor of Christ as a good, wise, and loving mother, I found myself both moved and unable to find anything theologically wrong with her analogy. I know this teaching is a stretch for anyone from a protestant background. But before your guard goes up, I invite you to stay with me while we walk through this idea, and let me unpack what I believe is not only a sound metaphor, but a useful and needed one. And, of course, why we should be careful not to misuse it. Julian begins her metaphor by talking about how Christ takes on the role of a mother in his work of creation, redemption, and renewal. Athanasius, in his beautiful work On the Incarnation, draws a parallel for us between the Word that God used for creation in Genesis 1 and the Word that is referred to in John 1 by saying: “The renewal of creation has been wrought by the Self-same Word who made it in the beginning.” The Word, we understand, is none other than Jesus Christ, the second person of the Trinity. In this grand act of creation, redemption, and sustenance, Julian sees the characteristics of a mother: I understood three manners of beholding our Motherhood in God: the first is grounded in our nature’s making; the second is taking of our nature— and there beginneth the Motherhood of grace; the third is Motherhood of working [here she refers to how Christ enables us to be sanctified]— and therein is a forthspreading by the same grace, of length and breadth and height and of deepness without end. And all is one love. (Ch. LIX) It’s not difficult to see the parallels between the act of birth that an earthly mother performs and the creation of our beings by the Word (Christ). It’s also easy to see how a mother’s care and devotion to her children is similar to how Christ sustains and upholds our very beings. Julian then draws a parallel between a mother breastfeeding her children and how we feed on Christ in communion: The mother may give her child suck of her milk, but our precious mother, Jesus, he may feed us with himself, and doeth it, full courteously and full tenderly, with the blessed sacrament that is precious food of my life; and with all the sweet sacraments he sustaineth us full mercifully and graciously... The mother may lay the child tenderly to her breast, but our tender Mother, Jesus, he may homely lead us into his blessed breast, by his sweet open side, and shew therein part of the Godhead and the joys of heaven, with spiritual sureness of endless bliss. (Ch. LX) It was when Julian began to unpack even further how Christ is like a good mother to us that I felt the metaphor become truly compelling. The mother may suffer the child to fall sometimes, and to be hurt in diverse manners for its own profit, but she may never suffer that any manner of peril come to the child, for love. And though our earthly mother may suffer her child to perish, our heavenly Mother, Jesus, may not suffer us that are his children to perish: for he is all-mighty, all-wisdom, and all-love; and so is none but he— blessed may he be! He willeth then that we use the condition of a child: for when it is hurt, or adread, it runneth hastily to the mother for help, with all its might. So willeth he that we do, as a meek child saying thus: “My kind mother, my gracious mother, my dearworthy mother, have mercy on me.” And if we feel us not then eased forthwith, be we sure that he useth the condition of a wise mother. For if he see that it be more profit to us to mourn and to weep, he suffereth it, with ruth and pity, unto the best time, for love. And he willeth then that we use the property of a child, that evermore of nature trusteth to the love of the mother in weal and in woe. (Ch. LXI) To summarize: like a good earthly mother who allows her children to suffer in small ways as they grow and learn, Jesus lets us “fall sometimes;” but unlike an earthly mother who cannot be sure that no true harm will come to her child, Jesus as the true mother assures us that he will not let us perish. When we are afraid etc, we may run to Jesus and beg him for help. And when we need to scream and cry and weep, he allows us to do so as long as we need to, until we are quieted and comforted by his love. This is a beautiful and Biblical understanding of one of the aspects of Christ’s character. The image of Christ as our mother is necessary and important to us in the company of all the other metaphors of Christ that we are given. As Tim Keller stated in one of his sermons, it’s extremely important that we don’t cut out or over-emphasize any of the metaphors scripture gives us, because they are meant to work together to give us a full picture. It’s important that we understand that Christ is our brother, that he is our bridegroom, that he is our savior, that he is our creator, that he is our mother. Each of these give us an essential understanding of who he is and how we can approach him. And just as we can understand the metaphor of the bridegroom without believing that we will literally have a wedding with Christ, we can understand the metaphor of Christ as our mother without believing him to actually be a woman. The idea of Christ as a mother has been de-emphasized to the point of becoming obsolete in the protestant tradition. And yet Jesus refers to himself as a mother hen when he says: “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the one who kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to her! How often I wanted to gather your children together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings, but you were not willing!” (Matthew 23:37) There are other places in scripture that set a precedent for using feminine metaphors to refer to God. Psalm 131 says: “Surely I have calmed and quieted my soul, Like a weaned child with its mother; Like a weaned child is my soul within me.” Deuteronomy 32:18 speaks of God as a mother giving birth: “You were unmindful of the Rock that bore you; you forgot the God who gave you birth.” The book of Isaiah is rich with feminine metaphors, such as: “As a mother comforts her child, so I will comfort you; you shall be comforted in Jerusalem.” (66:13) “Can a woman forget her nursing child, or show no compassion for the child of her womb? Even these may forget, yet I will not forget you.” (49:15) “For a long time I have held my peace, I have kept myself still and restrained myself; now I will cry out like a woman in labor, I will gasp and pant.” (42:14) In the creation narrative itself, we are shown that God holds both male and female aspects within his character: “So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.” (Genesis 1:27) There is certainly a way to take all this too far. By and large, God refers to himself as male, and I believe we should do the same. And yet this is one thing I really love about Julian’s writing; she is very clear that Christ is a “he,” and yet he can also be seen as a mother. There is no reason not to use this analogy, just as we would consider it wrong to set aside the analogy of Christ as our living water or Christ as our brother. What I think often gets missed is how necessary this metaphor is. Christ has a male body; God the father most often refers to himself as male; yet it is theologically correct to say that God is neither male nor female. To look at God only through a male lens would be to negate certain aspects of his character. We are invited through scripture to understand both male and female gender in the character of God, and he provides metaphors of all kinds for us to try to comprehend this. It’s important to communicate just how essential it is for women to see their own gender reflected in the character of God. I’ll use this example: over the years, I’ve had a few different men read my books only to tell me how disorienting it is for them to read the stories, because they are forced to spend so much time trying to see and understand the world through a woman’s eyes. What I have gently tried to explain to them is that for women— particularly for women who study literature— trying to see and understand the world through the eyes of a gender not our own is our most common experience. It’s helpful and good for me to look at the world through the perspective of a man, but there comes a time when I need to rest and to be affirmed in my own experience of being female. This is something God himself provides when he gives feminine metaphors for his character; and for the church to take this away from female Christians is reprehensible. It is detrimental to men in the church as well; if God did not intend for us to understand him through both male and female analogies, he would not have included them. Just as God is without gender and holds both male and female within his character, men and women are invited to understand God through the eyes of their own gender, as well as through the eyes of the opposite gender. Whether we feel comfortable referring to Jesus as “Mother Christ,” as Julian does, there is great value in this metaphor of his wisdom, love, and mercy, and we would do well to explore it. Let’s stay away from the pendulum swing (we can see and understand the metaphor without turning away from the masculine pronouns God uses to refer to himself) but let’s also not be ruled by fear when it comes to the words of scripture. Along with Julian, we should rejoice in this maternal understanding of Christ’s goodness and love. The food of mercy that is his dearworthy blood and precious water is plenteous to make us fair and clean; the blessed wounds of our savior be open and enjoy to heal us; the sweet, gracious hands of our mother be ready and diligently around us. For he in all this working useth the office of a kind nurse that hath naught else to do but to give heed about the salvation of her child. It is his office to save us: is it his worship to do for us, and it is his will that we know it: for he willeth that we love him sweetly and trust in him meekly and mightily. And this showed he in these gracious words: I keep thee full surely. (Ch. LXI)  Rahab Lets the Spies Escape by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld There is a baby explosion happening in my family right now. One of my sisters-in-law is pregnant with what will be my sixth niece or nephew, and it doesn’t look like the baby train is going to slow down any time soon. With all these new lives and names appearing among us, I have found myself also considering baby names. “Bruce,” I asked my husband recently, thinking about a woman whose story touched me deeply, “What do you think of the name Rahab?” His eyebrows rose. From his reaction, I could see that Rahab is not one of the “acceptable” Bible names; her story is considered too risque. Yet his reaction confused me. When I look at the way scripture itself treats Rahab, I find that it does not treat her with this same skepticism. As I’ve mulled it over, I have come to believe that the way Rahab is viewed by the church reveals a deep misunderstanding of the stories in the Bible and the way Christians understand grace. First, let’s take a look at some of the commentary on Rahab. Many of the ways Rahab’s story has been interpreted are deeply troubling. One commentator titled his chapter on Rahab: “How to Listen to a Shady Lady’s Story.” Commentator David Guzik writes: “We may be appalled at the fact that Rahab was a prostitute or that she was a liar but the fact is that she was not saved by her works but by her faith.” Perhaps worst of all, Herbert Lockyer writes in his book All the Women of the Bible: Like many a young girl today perhaps she found the restrictions of her respectable home too irksome--she wanted a freer life, a life of thrill and excitement away from the drab monotony of the home given her birth and protection. So, high spirited and independent, she left her parents and set up her own apartment with dire consequences. This speculation is not just troubling, but presents an irresponsible understanding of history and society. Given the time period, Rahab’s most likely backstory is that her family could not pay a debt, and sold her into prostitution. Even a cursory understanding of the sex trade reveals that almost every woman or child involved has been forced into it, either by other people or by the most desperate circumstances. Yet the idea that Rahab was a “shady lady” who somehow chose this life has prevailed in the church. I could say a lot about this. We are at a crucial moment in the church, when we are grappling not just with #metoo but also with the idea of women as writers, theologians, preachers, and speakers. And while the way Rahab has been treated by the church does make my blood heat, I believe the most useful thing for us is not to cast blame, but to look at how scripture itself treats her. Time after time I have been humbled and encouraged by how the Bible honors and upholds the stories of women in a way that is completely countercultural, elevating the women society discounted and using their lives as integral parts of God’s plan. So what does the Bible actually say about Rahab? The first time we encounter her is in Joshua 2, which tells the bulk of her story. However, she is also mentioned in four other places throughout scripture--later, in Joshua 6, which continues her story; in the genealogy of Jesus Christ in Matthew 1; in the famous “Hall of Faith” in Hebrews 11:31; and in James 2:25 . Rahab is not only mentioned frequently, but she is twice held up as an example of faith and is given a place of honor in the lineage of Jesus himself. If you haven’t read it recently, I entreat you to go read Rahab’s story in Joshua 2. She certainly shows courage and cunning, but the emphasis of her story is not on her own actions, but on her words about who God is. In the previous books of Exodus and Numbers we have been living with the Israelite’s disbelief and unfaithfulness despite God’s promises, and here at the beginning of Joshua, as they are poised to enter the land God has told them time after time he has prepared for them, we hear the strongest invitation to trust God’s word coming from the lips of a marginalized woman: I know that the Lord has given you this land and that a great fear of you has fallen on us, so that all who live in this country are melting in fear because of you. We have heard how the Lord dried up the water of the Red Sea for you when you came out of Egypt, and what you did to Sihon and Og, the two kings of the Amorites east of the Jordan, whom you completely destroyed. When we heard of it, our hearts melted in fear and everyone’s courage failed because of you, for the Lord your God is God in heaven above and on the earth below. (Joshua 2:8-11) Rahab is the mouthpiece of God’s glory and the reminder of his promise. She, a woman who did not know anything about the God of Israel except what she’d heard through tales from travelers in her city, has risked her life and her family’s lives because she is sure that what she has heard is true and trustworthy. The beauty of her story should bring us to tears. And yet it’s fundamental to our understanding of the text to realize that the emphasis is not on Rahab. She, like all the characters in the Bible, points not to her own story, but to God. It’s this that is the crucial misunderstanding in the way the church has treated her throughout the centuries. If we are looking to Biblical characters as examples of who we should be, we will pick and choose among them. We will encourage our children to be like David and Gideon and warn them against being like Rahab. This misses the reality, though, that every story in the Bible is a story of failure. Wasn’t David guilty of murder and rape? And yet we are happy to name our sons after him. This incongruity reveals not only that we must reckon with how women have been seen and talked about in the church, but also that we have a surface reading of our Bibles. Tim Keller discusses this when he talks about our tendency to look at the stories of Biblical characters and try to pattern ourselves after them--to try to be as faithful as Abraham, as strong as Moses and as brave as David. He says: You’ve read the Bible but you don’t know who the hero is... The reason you’re all screwed up is because you thought all the stories were about you. You thought that you were the hero. But every one of those stories points to [Christ]. [He] is the true Abraham, the true Moses, the true David. We are given stories of Abraham, Moses, and David failing for the very same reason that we are told that Rahab was a prostitute--so that we know not to pattern our lives after these characters, but to seek after the God who found and rescued them. The fact that we want to name our sons David but not name our daughters Rahab shows that we want the stories of the Bible to be about us. We want to believe that we can be courageous like David, instead of understanding that we are all broken and it is God who has redeemed us. The story of Rahab is especially important because in it we cannot deceive ourselves; we can ignore the fact that David was a terrible father, we can ignore Jacob’s lies, but we cannot ignore the fact that Rahab was a prostitute. It’s part of her identity, and the Bible is not ashamed of it. Only those of us who are in love with the idea that we can achieve God’s favor instead of casting ourselves upon his mercy, no matter who we are or what we have done, are ashamed of Rahab. I would be proud to name a daughter Rahab. Scripture holds her up as an example to us not once, but four times, of what it means to be grafted into the family of God. Her life reveals that nothing we can do, and nothing we have done, makes any difference in the way God loves us or uses us. It’s time the church let go of the misunderstandings surrounding Rahab, and rejoiced in her story.  Are you willing to do whatever God says in scripture about this area whether you agree with it or not? Are you willing to accept anything that God sends--anything that happens in that area--whether you understand it or not? These words, spoken by popular pastor Tim Keller, gave me pause. I have been listening to his excellent sermon series on wisdom and the book of Proverbs, and into the middle of a sermon called “Knowing God,” Keller dropped a question that I’ve been thinking about quite a lot recently: am I willing to believe that something God says can be true even if I don’t agree with it? This seems like a dangerous question. In our intellect-heavy world, the idea of not just believing, but acting upon a belief that seems contrary to our best intuition feels crazy. To complicate the matter further, American Christians have often erred too far on the side of blind belief without fully investigating their faith from an intellectual standpoint, and it’s been detrimental both to them and to those who are looking on. Yet as I continue to think through this idea, I would argue (and so, apparently, would Tim Keller) that the answer must be yes. Part of being a Christian is being willing to believe truths that we don’t necessarily agree with. This does not mean checking our brains at the door or having the “blind belief” that has been a fear-filled reaction of some evangelicals to the rise of science. Mine is a family full of scientists, historians, and mathematicians--which doesn’t mean we’re more curious or more intelligent than others, but it certainly means that none of us have been sheltered from the conclusions of science or the cycles of the past. I want to be clear that by approaching the topic of a wisdom beyond our reach, I am not saying that Christians should hide from knowledge. Rather, I am realizing that what I and so many other Christians lack is a proper sense of humility. A common theme in a lot of my most recent posts has been the idea that God is God and we are not, and that is because it’s been the lesson God has hammered into my own heart consistently over the past year. Though I am, generally speaking, a feeler and not a thinker, I’ve found myself on a logical exploration of the Christian faith that has led me to the very question Keller posed. I love my generation. But I will be the first to admit that our emphasis on feelings while also being on average the most highly educated generation to date has led to some pretty serious pitfalls when it comes to humility. This has translated into Christians who have emotion-led difficulty with certain doctrines of the church, and who have concluded that if they (and the larger culture) feel like a certain doctrine must be wrong, it can’t be believed. (A classic example is the statement: “I can’t believe in a God who would allow suffering.”) But this way of coming at truth is extremely self-centric. No one should or can be forced to believe anything they don’t. And yet if God does indeed exist, he doesn’t particularly need our belief. Whether or not we have a hard time believing that something he said is right or true, if God is who he says he is it doesn’t really matter what we think. It’s important, especially for those who have been raised as Christians, to not get the progression wrong. Rather than beginning with how we feel about God’s commands, it’s important to go all the way back to the beginning. Is God real? If yes, is the God of the Bible the real God? If he is, can we trust the Bible and rest on the fact that it is the actual communication of who he is and what he desires? If the answer to all of those questions is yes, our correct response is humility, and a genuine desire to see what he says, not a quick rush to translate our cultural perspective onto the words of scripture. Part of the problem is that in order to truly follow the commands of God, we have to know scripture. Not what our favorite blogger said about scripture, not what C.S. Lewis or Rachel Held Evans said about it, not what a certain cultural movement or faith tradition said about it: we have to know what scripture actually says. As helpful and illuminating as all of those sources may be (and trust me, my life has been changed by other writers and thinkers) when we face God we will not be asked what our pastor or our favorite writer believed--we will be asked what we believe. If we claim to follow Christ and yet do not know his Word, we are lying to ourselves and to others. Interpretation is a real thing; every believer is called to read and pray that the Spirit will help them interpret what the Word says, and I believe that sincere Christians do interpret certain aspects of scripture differently (see Why We Need to Disagree.) But there is a vast difference between earnestly reading and seeking a correct understanding of scripture and claiming that we don’t believe certain things about God because we just can’t understand how he would ask them of us. The Bible claims that our understanding is shadowed and our hearts are treacherous (Jeremiah 17:9, Romans 7:15-20, Proverbs 3:5 etc); if we believe that scripture is the Word of God, we must acknowledge that this is true. Some of the things that feel “problematic” in scripture may require us to humbly admit that only God completely comprehends them (like predestination) or admit that they are things we simply don’t want to believe are wrong (like sleeping around.) There are parts of scripture that we will not want to believe because we are frightened, or selfish, or conceited. Some of our parents and grandparents chose to ignore the way scripture treated things like racism, the love of money, and being holistically pro-life. All of these things probably seemed like no-brainers to them--everyone else was doing it. How could they have fathomed standing against the popular teaching? Yet we see what damage has been done because they did not earnestly seek the truth of God’s word, even when it went against what they wanted, and what culture preached. Though it changes in specificity with each era, every generation will encounter certain commands in scripture that seem countercultural to the point of being wrong. It has always been that way, and it will always be that way until Christ returns again. The question is not what we can bring ourselves to believe, but what scripture honestly says, and how we will conform ourselves in prayer and humility to submitting to the will of God--the all-knowing, all-powerful, and all-loving God who in his gracious kindness has chosen to draw near to us. Thank God that he is good, and that his commands lead to a truly beautiful life. For further reading:

I was getting drinks with a friend of mine recently, and she asked me a question I’d never thought about before. This friend had asked to get together specifically to talk about the topic of women in the Bible--one I care deeply about and have been steadily investing more thought in. She has her own questions about how God sees women, and about the differences in complementarianism and egalitarianism*, and she asked me: “Why aren’t there any couples in the Bible who are really good examples of male and female relationships?” I was stunned by her question. Though I would argue there are a few instances of couples in the Bible who portray a healthy male/female dynamic (such as Ruth and Boaz) by and large she’s right--the vast majority of stories we’re given involve broken and sometimes truly horrific examples of men and women sinning against each other. Regardless of how one approaches the question of complementarianism/egalitarianism, her question is a very valid one. Why would God not provide an example to us of a blueprint for how men and women can thrive? Why would he not give us a model for how to treat one another, especially when it comes to things like marriage? I have two answers--one that was immediate, and one that has come after mulling over the question for some weeks now. My first answer was this: there aren’t any examples of perfect male/female relationships in the Bible because it is not about us, it is about God. I know how trite that sounds. Yet while it’s easy to say that the Bible is about God, it’s far from easy to believe it. This is why Sunday School teachers so often emphasize Biblical heroes like David and Abraham and Sampson instead of discussing their constant failures; we crave humans to aspire to be like. But the Bible is relentless in its emphasis on our own failures and its message of God’s faithfulness. We are not allowed to make an idol out of any of the humans in the Bible because it is God we must worship, and God alone. The way relationships between men and women are depicted in scripture is no different; each story highlights the brokenness of humans and the faithfulness of God. Looking from the way Abraham cowardishly passed Sarah off as his sister to save his own skin, to how Rebecca deceived Isaac, to how David treated his many wives can be truly disheartening. These stories, and the many examples of women being abused within the pages of the Bible have caused both men and women to ask whether the Bible upholds and celebrates an ethic of abuse and the subjugation of women. And yet the way we interpret these stories rests precisely in our understanding of my initial thought: the Bible only ever holds up God himself as the true example we must follow. Once we understand that we are not supposed to see the people in the Bible’s stories as examples to follow, but we are to see in their lives the brokenness of humans and the fact that God is displeased with them, it all makes sense. The Bible forces us to encounter the common failure of humanity and recognize the fact that there is something fundamentally wrong with the way men and women interact, and we cannot solve it by ourselves. There is no example of a perfect man or a perfect woman to point to in scripture because there will never be a couple perfect enough to warrant our imitation. As I’ve thought this over, it has brought me to the second answer to my friend’s question: the fact that there are no perfect examples of male/female interaction in the Bible is actually really good news for us. Though the weight of our constant failure as people may seem disheartening, the stories of those who messed up over and over in scripture is a lifeline for anyone who has truly reconciled with his or her own sinfulness. I know my own heart well enough to know that I will never have a perfect marriage. I know the marriages of those close to me well enough to know that though I can follow their example in some ways, they will always disappoint me as role models. Instead, I am encouraged when I look to scripture and see people exactly like me--cheaters, liars, selfish people--who were shown grace. Who were still used in God’s rich and beautiful story--whose names were recorded not because they did anything special, but because through them God chose to work and to fulfill his purposes. As I thought through my friend’s question, and thought about men and women in scripture who treated each other as they were meant to, the best role models I could think of (other than Adam and Eve before the Fall) were Mary and Joseph. They certainly were not perfect, but I love the way God used and blessed them. Empowered by the Holy Spirit, Mary models courage to us--saying yes to the terrifying prospect of having a child out of wedlock in a society that would stone a woman for such a thing. Guided by a dream sent from God, Joseph models the self-sacrificial love Paul talks about in Ephesians 5:25 and not only believes what Mary tells him, but changes his course of action based on that belief and joins her in the call God has given her. Their story punctuates just how much our relationships with the opposite sex--and particularly our marriages--need the work of the Spirit, and this is something to take seriously. Together, Mary and Joseph give us a glimpse of what it means to be united to Christ--not that we will be made perfect in this life, for they certainly also had some spectacular failures. Instead their story highlights the great relief in the knowledge that we, like the rest of the men and women in the Bible, will never be the one people should point to. It is always God himself who deserves the glory and thanks for his lovingkindness to us. In a world of inequity and abuse, we can look to these stories and see that there is great hope in the redemption and reconciliation the Spirit brings to his people--both men and women. ____________________________________________ *A very barebones summary of the two viewpoints: Complementarians believe that “God created two complementary sexes of humans, male and female, to bear His image together. This distinction in gender represents an essential characteristic of personhood and reflects an essential part of being created in God’s image.” Egalitarians believe “that not only are all people equal before God in their personhood, but there are no gender-based limitations of what functions or roles each can fulfill in the home, the church, and the society.” Follow the links to read more about each position.  Recently I’ve been thinking about disagreeing with people: the way I approach it, the way I talk about it, the way I talk with and about those who disagree with me--all topics I encounter every day. Mostly, I’ve been thinking through how to disagree with other Christians, and that’s what I want to spend most of my time discussing here. To begin that discussion, I need to start a little further back, and talk about the difference in how believers are called to treat those inside the church in comparison with those outside the church. Until I moved to New York City in my mid twenties, I didn’t have an understanding of the distinction between how to treat those who profess the beliefs of the Bible, and those who don’t. I spent a lot of time as a teenager feeling angst about how I wasn’t calling my unbelieving friends out on the choices they made, and feeling a nagging guilt that I was somehow responsible for their morality. It was a hugely clarifying (and humbling) realization, therefore, to come to the place of distinguishing between my attitude toward believers and my attitude toward non-believers. An enormous amount of the New Testament is devoted to counseling and discipling those within the church and instructing believers how to treat one another. It’s important to note that these instructions are given specifically to those within the body of believers. This doesn’t mean the church has nothing to say to an unbelieving world--far from it. As Christ instructed in Matthew 28:19-20: “Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you.” In matters of harm to others (such as stopping the wrongful taking of life, or passing laws to prohibit abuse and extortion) there are clear commands for believers to intervene in culture. What I missed as a teenager is this: the starting place for believers is not telling someone who doesn’t hold the beliefs of the Bible that they’re violating the commands held within it, because those commands mean nothing to someone who doesn’t believe in the God who put them in place. The great commission is a call to “make disciples” by sharing the good news of the gospel, modeling a Christ-like love, and being orderly and charitable to other believers within the church. We can’t put the cart before the horse--as the church so often has--and call people to repent of their sins before the Spirit has revealed himself and convicted them of his presence and their own need for the words of scripture. This was a revelation to me in my mid-twenties, and it’s completely reoriented my relationships with people outside the church. By removing myself from the seat of judgement, I am actually freed to live more fully as a believer and to joyfully proclaim the invitation of God’s grace, trusting that he will continue the work he is doing in the hearts of those around me. And yet the longer I am in leadership in the church, the more I see why the long letters in the New Testament to believers are necessary, for we in the church do not know how to disagree. The first step, of course, is agreeing that it’s okay to disagree. During my undergrad, I remember a fellow student telling me that he felt all believers should join the Roman Catholic Church even if they held severely different beliefs, because according to him the most important aspect of belonging to the church was unity. (For the record, he did not hold to many Catholic beliefs himself.) I understand this view, and I get where he was coming from, especially with the legacy of so many non-denominational churches in the US that are sort of lone-rangers, totally divorced from much of the historical church and creeds. But his argument also sort of feels like the argument for complete cultural homogenization, which is essentially negating the experiences and cultures of minorities. The church is stronger when it allows for theological diversity among its many members, especially now that more women and more cultures outside the West are coming to the table (such as the burgeoning church in China or the vibrant Anglican, Baptist, Pentecostal etc churches across South Africa, Nigeria, and many other nations.) Opening the door to disagreement, however, is inarguably scary. We believe that the Bible holds life within its pages, and Christians are rightly concerned about taking its words and their own interpretation seriously. As a Presbyterian, it should come as no surprise to anyone that I believe theology truly matters--whether it’s in the way I understand my own personal life and problems, or the way the church at large operates. It matters a lot. With this in mind, I believe there are three helpful ways of viewing conflict that have the ability to transform the way the church deals with disagreement: first, a correct understanding of first and second order issues, second, a true sense of personal humility and respect for other believers, and lastly, a real understanding of God’s sovereignty. Understanding first and second order issues. When I lived in New York I attended an Evangelical Presbyterian Church (EPC), and though I’ve since gone back to the Prebsyterian Church in America, I gained a lot of respect for the EPC because I feel that they have a great understanding of how to agree on certain issues, and disagree on others. Their denomination is built on the concept of first and second order issues, which is this: there are some things that Christians must believe in order to be Christians (first order issues) and there are some things that it’s okay for believers to have a breadth of opinions on (second order issues). By placing some things in the category of second (or third, or fourth) order, Christians are essentially saying that as long as those first order beliefs are aligned, they can work with and fellowship with other Christians as co-laborers in the service of Christ. First order beliefs are typically doctrines such as the inerrancy of the Bible, belief in the Trinity, belief in the physical death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, etc. Second order beliefs can be anything from the gender of elders to the age of the earth to infant vs. adult baptism. Second order issues can be very important, and yet we must be able to have disagreements in these areas and still have respect for those we don’t agree with. An often quoted example of this in the early church is found in 1 Corinthians 8, where Paul discusses whether it’s okay to eat food sacrificed to idols. He essentially says that some will make the choice to eat it, and some will not: “But food does not bring us near to God; we are no worse if we do not eat, and no better if we do.” (v. 8) Later in the same letter, Paul goes on to make the argument of first (and therefore second) order issues by writing: “For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures.” (1 Corinthians 15:3-4) Believers will disagree about the interpretation and application of scripture; it’s a part of our limited comprehension and wisdom as humans. How we disagree, and how willing we are to work with those we disagree with, is the important thing. This is all the more applicable with the recent celebration of Pentecost just this past Sunday. So much of language has the nuance of culture tied into it, and to quote my brother Daniel: “Language is more than information transfer, and the Holy Spirit speaks in all tongues. Theology of second issues is often challenging because the hermeneutics of our own interpretation is difficult to transfer culturally. In light of Pentecost, we are called to humility.” Respect for those we disagree with. This brings me to perhaps the most challenging point, and one that has been personally humbling for me in recent months. One common failing of Christians in my tradition (which places a lot of emphasis on understanding) is hubris associated with believing that we have all the right doctrines. I don’t mean to say that there’s anything wrong with spending time studying and interpreting scripture, and I don’t mean to say that believers should not seek to know what scripture is saying. Still, I have been convicted recently of my own limits of knowledge and understanding. In this respect I have been truly blessed by traditions that uphold and cherish the mystery of God, such as the Anglican church. I am thankful to be able to say that there are some things I may never have a satisfactory answer to, and the longer I am a Christian the more I understand that believing I can have a firm comprehension of every topic in the Bible is actually making God far too small. (Anyone who tells me they fully understand the doctrine of predestination, one way or another, either has a much too high opinion of themselves or hasn’t truly studied the words of scripture.) I am eager and excited to continue reading and interpreting the Bible for the rest of my life, and I am sure that my understanding of it will develop as time goes on. I have opinions about what I think scripture says on many issues. But to have a robust sense of the church and a true sense of self, I must admit that I can be (and often am) wrong in my own interpretation. I believe what I believe is right--otherwise I wouldn’t believe it--but I am also willing to admit that I may get to the end of my life and find out that I had interpreted a whole host of second order issues incorrectly. This doesn’t change my convictions now, but it certainly changes how I treat other believers. Each Christian looks to scripture and interprets it, and I am called to the humility of admitting that my interpretation may not be the correct one. Rather than locking down a set of beliefs and defending them until I die, I trust that the Spirit in me and my unshakable union with Christ will lead me through innumerable relationships with believers who disagree with me, and from whom I can learn and perhaps change. A beautiful example of this in action is the relationship of George Whitfield and John Wesley, two theologians and pastors who had severe differences in their beliefs. At times their disagreements led them to open conflict and to actively work against the other. Yet toward the end of their lives one of Whitfield’s followers asked him: “We won’t see John Wesley in heaven, will we?” To which Whitfield replied “Yes, you’re right, we won’t see him in heaven. He will be so close to the throne of God and we will be so far away, that we won’t be able to see him.” Whitfield requested that Wesley, who outlived him, give the eulogy at his funeral, and Wesley is recorded as saying: “There are many doctrines of a less essential nature with regard to which even the most sincere children of God…are and have been divided for many ages. In these we may think and let think; we may ‘agree to disagree.’” Assurance of the sovereignty of God. My final thought is one of great hope, because the Bible is not a story about us--it is a story about God and his glory. When I look around in fear--when I see the church today looking around in fear--I am called back to the many, many stories in the Bible in which God was faithful to his people and faithful to his own glory by upholding his church through the ages. He stayed with Abraham in Ur, he led his people across the Red Sea and the Jordan River, he brought them back from exile, he spoke to them through the prophets, and he came himself in the flesh to be present with us and to die for us. He expanded his church through persecution, he was faithful to the missionaries who went into Europe, he stayed with his people through heresies that threatened them. The church has expanded over the world, it has done true harm and true good, and today it is rich with a diversity of cultures, peoples, and beliefs. Whatever we can envision for the church through our tiny edge of understanding, it is far less beautiful than what God himself--who uses the church for his glory and his glory alone--envisions for it. He will always sustain a remnant of people who teach the truth, and the truth will never pass away. With this in mind, we have to approach our own disagreements with the humility they deserve. There is certainly a time to stand up for what we believe the Bible is saying, and a time to confront the church when she preaches heresy on first order issues. But God has not and will never stop being faithful to his people. If he can use me, he can certainly use the believers I disagree with. My prayer is that I will believe what I believe with conviction, trusting the Spirit who enables me to understand the word of God, while maintaining a posture of humility and grace toward my brothers and sisters who interpret the Bible differently. Artwork: "The Chasm of Otherness," by Bruce Buescher  For a long time now I’ve believed that my life will have a beautiful trajectory. Not necessarily in the things I accomplish and certainly not in material possessions that I own. Rather I’ve always assumed that as the years progress and I grow older my spirit will age with grace, and as I continue to be sanctified (the process through which the Holy Spirit makes believers more and more like God) I will live with ever more wisdom and stop doing the things I loath. I know plenty of beautiful, seasoned believers who certainly live in wisdom and grace. However, my surety of this peaceful future self has been challenged recently by two things: first, by the stories I’ve been studying in the Old Testament, and second, by the reality of how sanctification actually feels. In general, studying the Old Testament more closely has challenged the way I (and many other Sunday school taught children) understand the Biblical characters. Whereas people like David, Abraham, and Esther are often taught as examples of faith we should aspire to be like, I’ve been hit strongly by the fact that the Bible itself does not treat them this way. While there are certainly a variety of lessons to take from their stories, the most important lesson is always that they failed, and that God was faithful. The famous “Hebrews Hall of Faith” is not, as I and so many others assumed, primarily pointing out great examples of the faith we should aspire to be like. It is pointing to one example who was faithful to all of the people listed--God himself--and showing how he used them in his story. More than this, I’ve been struck by how poorly so many of these lives ended, and it’s this that has challenged my subconscious self-trajectory. The list is endless...Jacob, who ended his life dividing his sons with favoritism, Hezekiah who let pride and avarice color his final years, Solomon who gave into his lust and let it drag him away from worshipping God alone, Rebecca who turned to trickery and deceit. After spending time in 1 and 2 Samuel I’ve been particularly struggling with the story of David. Of all the Biblical characters, David is probably the one people know best and understand least. We are taught about his defeat of Goliath, the way he danced in worship, the fact that he is called a “man after God’s own heart.” We are taught about how he exploited Bathsheba and how he repented. But we are seldom taught of his latter years, when his family fell apart because of his impotence as he stood by and watched his own son rape his own daughter. I struggle hard with this. The way David takes no action on the behalf of his daughter but rather grieves for the death of the son who raped her, the way he ceases to be an effective ruler until his army captain Joab has to chastise him--these things don’t work with the idea that he is supposed to be a shining example to us of a faithful follower of God. My hope that I will progressively stop sinning and enter into a life of peaceful fellowship as I near my death is blown to bits by the story of David and his grievous final years. If this “man after God’s own heart” could end his life like this, what can I hope mine to look like? Compounding this realization is the second thing I mentioned--the fact that sanctification feels different than I expected it to. I assumed that since coming to know God better is the best possible thing I can imagine, it would result in the best possible feelings I can imagine. Wrong. To come to know God better in this place of in-between, when I am not yet fully sanctified, means that I grow progressively more grieved with my sin, as God himself is grieved. In a previous post I shared the verse Galatians 2:20, which says: “It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me.” The tension of the spirit of God dwelling within my still sinful self results in a daily grief that grows more intense as time goes on and as I understand just how deep and foul my sin is--as I see it with the eyes of Christ. The answer to all this is a reshaping of my understanding of both sanctification and the stories we are given in the Bible, because the honest truth is that my hope for a progressively more holy self is nothing more than a desire for an easier life, and a prideful search for self-promotion. Most of the time I don’t care about truly knowing or becoming more like God--I just want to be seen as a mature and wise Christian, and I want to stop having to battle with myself because it’s hard. It’s tiring to constantly see my sin; it’s difficult to be grieved. The stories in the Old Testament give us something better than human examples to look to and aspire to be like. These stories give us the one thing we can truly cling to: that our union with Christ is not dependent on our own trajectory or our own Christian life. I pray that God would draw near to me, that I will have a repentant heart and that at the end of my life I will be living so that all can see I am truly no longer alive and that Christ lives in me. But I know that even if I fail as spectacularly as David did, it cannot shake my union with Christ. If I’m 70 years old and still struggling to control my tongue or secretly planning my own self-promotion, I can look to scripture and rejoice that as John Newton, the author of the hymn “Amazing Grace” wrote: “Although my memory's fading, I remember two things very clearly: I am a great sinner and Christ is a great Savior.” The weight of sanctification is heavy, and the grief grows ever greater--but so does the joy. For all that I had hoped sanctification would feel like entering into a blessed numbness, I would not for the world now trade the sharp, sweet relief of my thankfulness. Perhaps when we are finally glorified and fully sanctified we will retain a memory of our former state, because without a true understanding of my sin, I could not experience the ocean of mercy God has lavished on me. Like David I marvel: “Your steadfast love, O Lord, endures forever,” and pray: “Do not forsake the work of your hands.” (Psalm 138) |

Currently Reading

Open and Unafraid David O. Taylor O Pioneers! Willa Cather Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|